EIA put out a timely reminder of the big picture for US oil. There has never been more proved reserves or production:

A big part of this is the economics of shale oil.

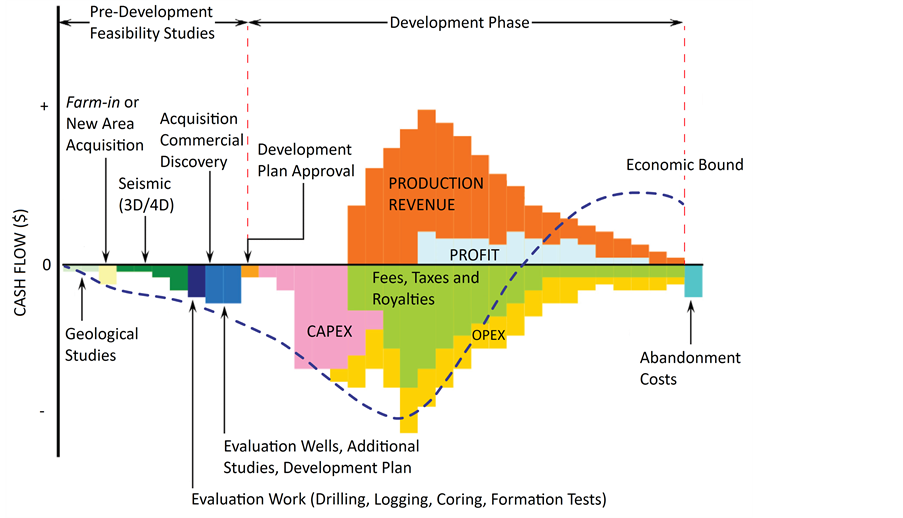

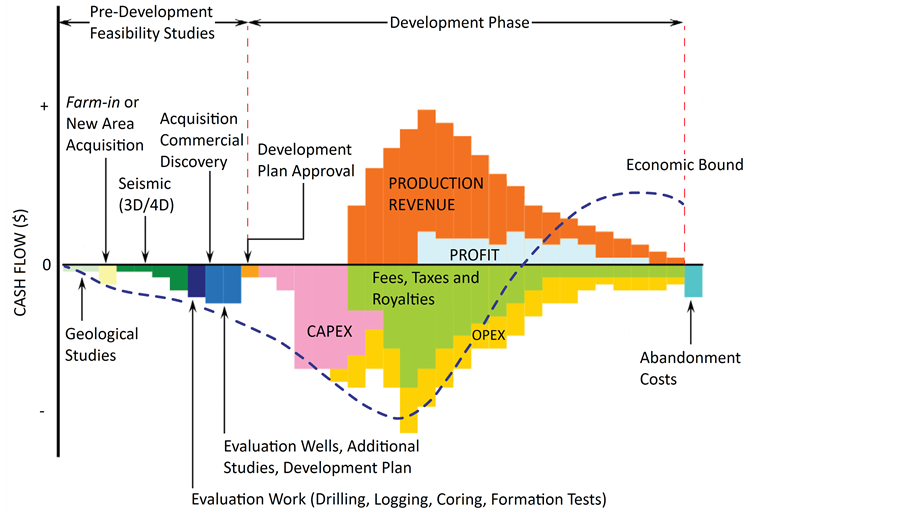

A typical oil well has economics that looks something like this:

Source: Changing Paradigm for the Oil Industry: From Peak Oil Production to Peak Oil Demand

Basically, oil wells lose money for years, then become incredibly cashflow positive before tapering off over the final years.

Shale oil wells are different in two respects:

- The timeline is much more condensed. Rather than the x-axis of the above chart being measured in decades, its measured in months.

- The production output is radically different – production falls away exponentially over the first two years – see below for a sample well in the Bakken vs a conventional well:

A first, the huge declines in production for shale wells seem like a negative. But from an investment perspective, the declines are a huge positive – i.e. if you knew you would get 10m barrels of oil from a well over ten years, would you prefer (a) 1m barrels per year or (b) 8m barrels in the first 2 years and 0.25m barrels for the next 8 years? Investors will take option (b) every time as you get your money back sooner.

The chart below shows how the production “spike” is growing as fracking technology improves:

The next major innovation is the financing side. When you are building a conventional well with a 50-year lifespan, you can’t hedge your production as there are very few investors willing to take on such long-dated risk.

However, for a shale well that gets most of its investment back in a few years, it is possible to hedge your cashflows. So, the investment profile turns into:

- Insert some equity to “prove up” the oil reserves

- Borrow money to complete the capital expenditure phase

- Hedge enough of the first few years production to bring borrowing costs down (i.e. lock in a price to reduce the risk for debt holders)

- Use the spike in production/cash in the first few years to pay back most of the debt

- The rest of the cash flow is the profit

This means that the forward oil price is now much more important – if you can hedge 2-5 years of production in order to pay your debt holders then it is much easier to get enough money to drill the oil well. Twenty years ago the two or even five-year forward oil price made little difference to an oil producers decision about whether to invest. I am arguing that today these prices are much more important to the future of production.

And at current levels, the forward oil price doesn’t seem to be low enough to slow US production:

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at the Macrobusiness Fund, which is powered by Nucleus Wealth.

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen is an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management, a Corporate Authorised Representative of Integrity Private Wealth Pty Ltd, AFSL 436298.