A client asked us to look at a recent Bridgewater post titled It's Mostly a Demand Shock, Not a Supply Shock, and It's Everywhere, which has some important points to make. We have been taking the other side of the debate, and it is worth looking at the arguments in detail.

Bridgewater's view:

Even as supply disruptions and higher inflation persist, markets are discounting that they will soon subside... We disagree. While the headlines tend to focus on the micro elements of the supply shock (the LA port, coal in China, natural gas in Europe, semiconductors globally, truckers in the UK, etc.), this perspective largely misses the macro cause that is likely to persist and for which there is no idiosyncratic solution. This is not, by and large, a pandemic-related supply problem: as we'll show, supply of almost everything is at all-time highs. Rather, this is mostly an MP3-driven upward demand shock. ... we see the underlying demand/supply imbalance getting worse, not better.

....

The issue is that demand has exploded, creating an imbalance of a magnitude that we haven't seen since the 1970s. The bottom charts show the current imbalance in historical perspective. What happened in the '70s truly was a supply shock: supply collapsed, and demand stayed relatively steady. Today, demand is surging, and supply is also growing, but it just can't keep up with demand.

The core premise of their argument is that the surge in demand is not going to abate and that supply cannot keep up.

In a simplified way, there are four possible outcomes:

- Demand stays strong, Supply can't expand fast enough: Inflationary

- Demand stays strong, Supply expands: Moderate Inflation

- Demand returns to trend, Supply can't expand fast enough: Disinflationary

- Demand returns to trend, Supply expands: Deflation

Bridgewater is arguing that both demand will be strong and supply problems will persist. i.e. if either doesn't occur, then the argument falls apart.

I haven't included two more possible scenarios: supply contracting or demand contracting. Partly because they weren't part of the Bridgewater thesis and partly because they are lower probability. Supply contracting is possible if we see more variants affecting supply. Demand contracting is possible if we see a "payback" for the increased goods demand resulting in lower goods demand for some time.

Can supply expand?

Metals:

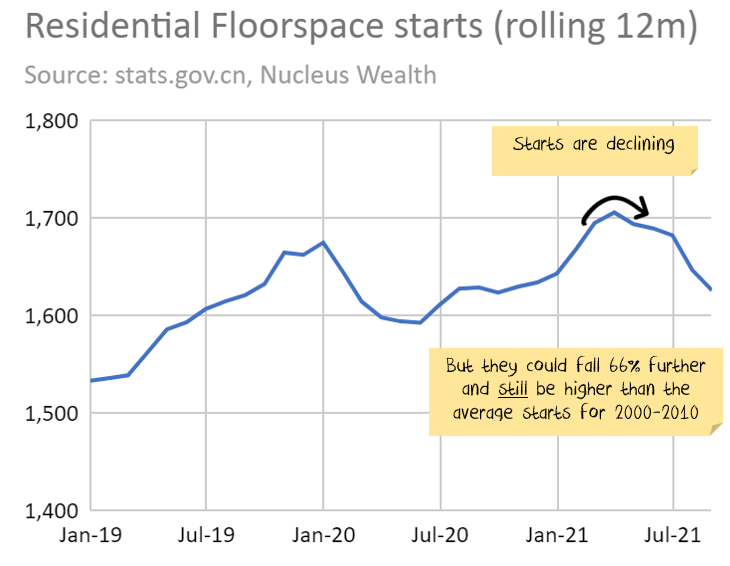

For metals, Bridgewater ignore the elephant in the room: Chinese property.

China uses an incredible amount of commodities relative to its size:

This is not a long-term phenomenon. It has arisen in the last 20 years. Here is the chart for steel; other commodities are similar:

Why does China use so much more commodities than you would expect based on population or economic size?

Partly because of the growth in exports. China now makes up almost 20% of all goods exports. However, this is not really new domestic Chinese commodity demand – rather displaced demand from other countries.

And what's more it is not even the main source of demand.

When you strip out this increased export-driven demand, Chinese steel demand per capita is still about double the average developed nation's levels.

The real culprit is the Chinese construction sector:

Net Effect: A bet on increasing metal prices is a bet that China will reverse current policy targetting property. It may happen. But that is not how it is looking now and if they are serious about reforming the property sector then the floor is a lot further away than the ceiling.

Energy:

It is a similar story for energy, but this time Bridgewater trivialises the Russian influence. Prices have rocketed in energy. But, there are two key political issues affecting supply:

- Russia would like to have Nordstream 2 approved

- Russia doesn't want to pay Ukraine or Poland

See if you can notice either of these in the charts:

Energy price jumps are real and economically damaging. Even so, to get further inflation, they need to continue. This may occur, but that will rely on both (1) Russian gas supply issues remaining unresolved and (2) goods demand remaining high.

Inventories

I agree that inventories cause short term inflation. But inventory shortages are not an argument for persistent inflation. Have a look at our inventory piece from the start of this year if you want more detail.

Shipping

Shipping costs are definitely higher, and there are delivery delays. There are three main possibilities:

- Demand will revert, and shipping costs likewise.

- Supply will expand, shipping costs will return to historical levels.

- The problem will not be solved for years.

In my view, the odds of the first two far exceed the third option.

Housing

I agree that low-interest rates, increased demand for houses vs apartments, and more work-from-home lead to housing inflation.

Labour

The labour argument is considerable and nuanced. And the area where my views are least certain. In my view, there are two likely outcomes:

- The high quit rates and difficulty finding staff reflect: skills shortages, health concerns, and increased early retirement. Higher wages will be needed to resolve the problem.

- Workers have decided that lifestyle is more important than higher wages. Your company won't let you work from home as much as you want? Quit and find one that will. Under this scenario, higher salaries won't fix the problem - companies may just need to hire more staff to do the same job. If this is the case, productivity, wage growth and consumer demand will be lower.

Both may be true in different industries. An oil engineer might leave for a desk job near the beach and a pay cut. But to replace them, the oil company may need to cough up a higher salary. A lawyer might decide to work only four days per week, regardless of the money on offer. The legal firm may need to hire more staff.

Also, as goods demand reduces and services demand increases, Bridgewater rightly notes that this will likely increase the demand for workers.

Net Effect: I'm not going to commit either way on wages. Bridgewater have some strong arguments.

Demand

Bridgewater's view:

Governments transferred a massive amount of cash to households, more than offsetting lost income from COVID. Household balance sheets are now in a materially better state than they were pre-pandemic, as [Monetary Policy 3] created a significant amount of wealth, pushing up the value of assets like equities, housing, cryptocurrencies, and so on. These gains have been broad-based across the economy, not just in the top decile or quantile. Ongoing stimulative financial conditions have further lowered debt service costs, and incomes have also benefited as economies have reopened. In short, households are wealthy, flush with cash, and ready to spend—setting the stage for a lasting, self-reinforcing surge in demand.

This is another nuanced argument. I agree with parts of it, I'm sceptical about other parts.

Overall demand

I agree demand is strong and there were large transfers from governments to households, though I note that these transfers have largely expired. Economic growth is about change. And fiscal stimulus is about to turn into fiscal drag (via Bloomberg):

It may be that a buoyant consumer will overcome the drag. But that is a more difficult argument than the one Bridgewater prosecutes in this post.

Goods vs services demand

Bridgewater pins a lot on the idea that goods demand will remain high in its supply-side arguments. They don't devote any space to supporting this in their demand-side arguments.

My base case remains that goods demand will fall and services rise. Goods demand will eventually settle a little higher than the previous trend and services demand lower for a few years.

Wrap up

Bridgewater is betting on strong demand, continued goods demand and constrained supply. Remove any of those factors and the investment case for continued inflation is much weaker:

- Demand stays strong, Supply can't expand fast enough: Inflationary

- Demand stays strong, Supply expands: Moderate Inflation

- Demand returns to trend, Supply can't expand fast enough: Disinflationary

- Demand returns to trend, Supply expands: Deflation

If we have further virus mutations that restrict supply and increase government stimulus then Bridgewater would be inadvertently right. But in our view, the odds of the other three scenarios eventuating is greater.

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at Nucleus Wealth.

Follow @DamienKlassen on Twitter or Linked In

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen is an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management, a Corporate Authorised Representative of Nucleus Advice Pty Ltd - AFSL 515796.

Tags:

Articles

December 3, 2021