All investment managers have an investment philosophy that explains how it is they seek to make money. At first glance, this would seem an obvious enough statement. But once you factor in the efficient market hypothesis proposed by Samuelson and Fama, the investment philosophy statement becomes intrinsically what the investment manager is offering to do for you. For this reason, I want to explore the Nucleus Wealth investment philosophy in some depth.

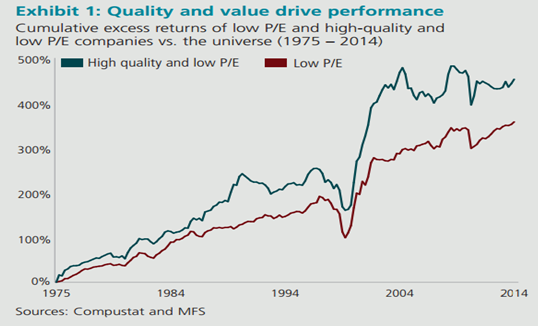

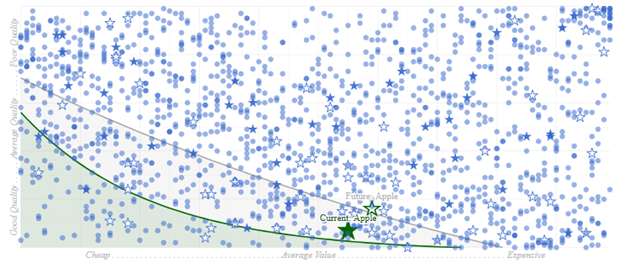

Nucleus Wealth’s investment philosophy is that high-quality assets at reasonable prices provide the best investment outcomes for investors. Studies show that not only do these assets provide higher returns over time, but the path is also much smoother. This is because the lowest quality and most expensive assets will often rise the most during bull markets and then fall the most during bear markets.

All this is a way of saying we’re looking for good quality assets at a good price because these provide the greatest returns over time, and also the least volatility.

So there’s the philosophy statement. Now how should you think about it? Let’s start with an explanation of the efficient market hypothesis and use this as a structure to understand the Nucleus Wealth investment philosophy.

The efficient market hypothesis states that asset prices immediately and instantaneously reflect all available information. I’ll explain using Tesla as an example. If we assume the efficient market hypothesis is correct, that means the current price of Tesla reflects all available information on the company. That obviously includes all public information, such as press releases and earnings reports. But it also assumes that all non-public information is reflected in the price. If the efficient market hypothesis holds, then internal knowledge about production issues, cashflows and funding would also be instantaneously reflected in its current share price.

The thing is, the efficient market hypothesis doesn’t hold. Frictions exist to prevent it from holding. These frictions take the form of:

- Regulation – Most asset markets are regulated by law, for example the Security and Exchange Commission in the U.S. and Australian Securities and Investment Commission and Reserve Bank of Australia regulate their respective share markets. Laws exist regarding the sale and purchase of property, from residential to commercial. And of course, banks are regulated regarding their activities from deposit-taking through to loan-making. This means certain practices required for all available information to be reflected in the asset price may be illegal, such as trading shares when you are aware of non-public information. On a side note: the trading of a company’s shares is the mechanism by which information is reflected in the company’s share price.

- Trade costs – There are typically fees attached to the trading of shares. And as they say, “If it’s free, you are the product”, so buyers beware in the case of Robinhood. Properties incur stamp duty, legal advice, and agent commissions. These costs make it prohibitive to trade on information that may move the price less than the cost of the trade (thus netting you a loss).

- Research – In the efficient market hypothesis, people who buy and sell assets are considered to be as perfectly capable and efficient as computers at processing information when it is released. This is clearly not true. And as algorithms and high-frequency trading have shown over the last decade, they are neither as good as the hypothesis’ authors imagined. When information is released, it requires people to analyse it, determine their expectations about what it means for the value of the asset, then place orders to buy or sell the asset according to those expectations. You’ll see how shares trade on the day their companies’ make announcements (see the Sydney Airport takeover example below), and it’s very rarely in a single step up or down to the new value.

Part of this is because the research takes time, but the other part is because many people interpreting the same information come to different conclusions about its implications for the share’s value, and with different confidences in their analysis. - And thus the final friction is human nature and its diversity.

Why is all this relevant to investment philosophy? Because the efficient market hypothesis implies that if it holds, it is impossible to sustainably generate better than market returns (often referred to as alpha).

Since we now know the efficient market hypothesis doesn’t hold, it now becomes possible to sustainably generate better than market returns. But the only way to do so is by identifying a way in which markets are mispricing assets (through a friction) and exploit that.

Hopefully, you can now see the Nucleus Wealth investment philosophy/strategy exploits the ‘Research’ friction mentioned above. It asserts that because of the breadth and depth of investor types, investment philosophies and analytical conclusions humans reach from the same information set, assets can become mispriced. Our process seeks to identify and invest in those mispriced assets to grow your wealth.

What this means in practice is that our funds should outperform falling markets, follow rising markets, but slightly underperform red hot markets.

If you’d like to hear more about different investment philosophies, we did a podcast with founder of Merricks Capital, Adrian Redlich in which he explores, among other things, the market frictions that his investment team exploit to generate market-beating returns for their clients.

If you’d like to explore how you can use the Nucleus Wealth investment philosophy in your investment portfolio, you can get in touch with us for a complimentary phone call with one of our financial advisors.