Last week I ran through the big long-term (20-40 year) economic trends (click here for the full post) that investors should be aware of, noting that a couple of these trends (women in the workforce, the ratio of workers to non-workers and maybe trade) are changing for the worse.

Stage two (today’s post) is looking at the medium term trends. I think about these trends as being relatively transient; they are imbalances that are in the system and will eventually be resolved. Some will end with a whimper, some with a bang. Sometimes they are like the tech boom or the US housing boom, up and down and all over in a few years. Sometimes they are like the Chinese capex boom and stretch over much longer periods.

After stage two we will look at the short-term trends and most importantly what is (or isn’t) priced into markets.

There are lots of mid-term trends at any one point in time, but only a few that are going to drive our key asset allocation weights. I try to keep my investment list to three or four big themes, as most of the others are peripheral. The three big ones I am following at the moment are: (1) Chinese capex/rebalancing (2) Trump tax cuts (3) European debt. I have a laundry list of minor themes that I’m keeping track of that may emerge as major themes.

The net effect of the medium-term trends is that I believe a classic boom/bust cycle driven by US tax cuts is looking likely. With the (major) caveat that it is hard to know what Trump will actually do.

Mid-Term Trend 1: Chinese rebalancing

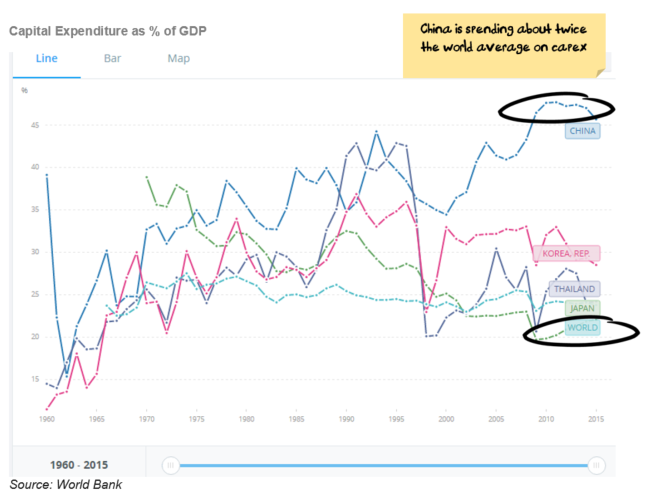

China is spending just under half of its GDP on capital expenditure, new roads, bridges, factories, airports and buildings. This level is much higher than any similar country has ever spent on capex since we started keeping records – the only country that came close was Thailand shortly before the Asian Crisis (for anyone not sure how that ended for Thailand, the word “crisis” is instructive).

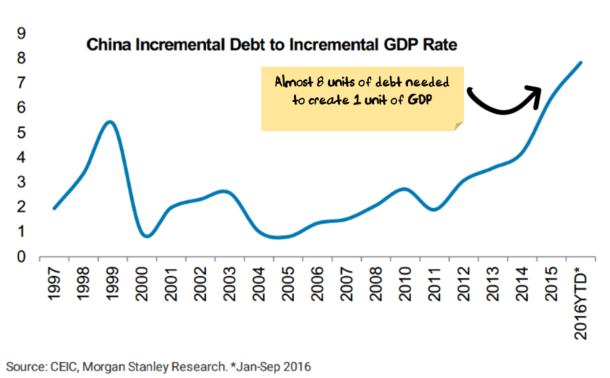

The spending, is increasingly debt funded, and each dollar of debt is having a smaller and smaller impact:

Sometimes it’s hard to grasp that not all investment is good. Specifically, an investment that does not earn a high enough return is not a good investment. Judging returns is hard enough to measure for commercial operations but when you are building things like bridges or roads then measuring the return as a “public good” is even harder again.

The parable here is that when you first start spending on capex you choose the most efficient investments first (give or take) and as time goes on you invest in projects that earn a lower and lower marginal return. For example, the first bridge across a river is very productive as it may save hours of transit time, the second less productive as now its saving transit time from congestion on the first bridge, and by the time the third and fourth bridges are being built the benefits are more and more marginal (and harder to measure).

At some stage, if the level of investment is high enough, this return will fall below the cost of capital – the key question is when? In my view, China is likely to have surpassed this level a few years ago – as the above chart indicates.

When does this end? i.e. how much debt capacity does China have left?

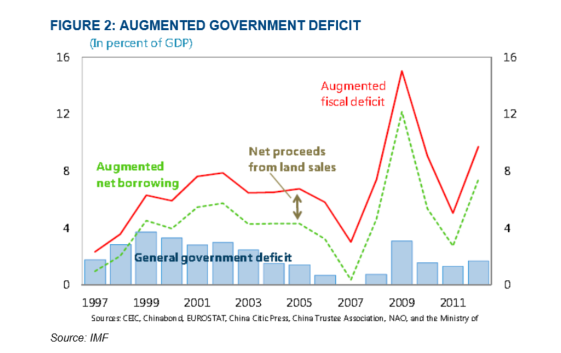

Chinese debt is high at around 280% of GDP. Its government deficit is running at close to 10% of GDP if you include debts being accrued by local governments.

So, not much debt capacity left. Having said that, China could probably scrape another few years out without too many issues. But, the current path is clearly unsustainable.

If we assume at some stage the Chinese economy will rebalance, then the key questions become how and when?

For the “how” question, we are unsure - in the vast majority of similar cases, investment spending continues to increase as long as it can before ending in a crash (e.g. Russia, Japan, the Asian crisis). Basically, the level of investment spending gets so high the entire economy becomes dependent on creating investment, and it is hard politically to diversify away from this as it involves short term pain for a longer term gain.

There is some hope that this time China will be able to rebalance more gradually – they have recognised the problem at least in their five-year plan, the question is whether politically it is possible to make the change given:

- it is likely to generate higher short-term unemployment

- local governments have become dependent on profits from land sales

- vested interests will likely lobby to maintain the construction spend

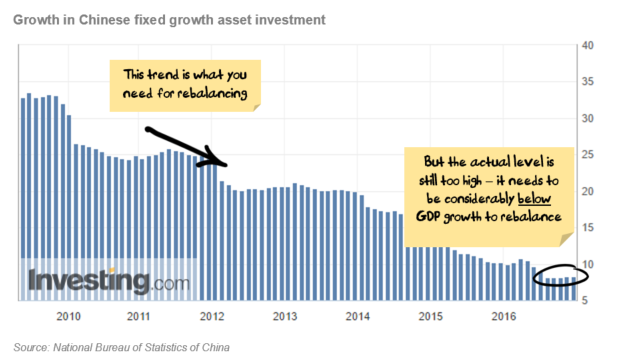

Forgetting the political issues for a moment, let’s make the assumption that China wanted to rebalance smoothly over the next ten years back to 50% consumption, 30% investment (which would still put them at the top of the world for investment as a % of GDP).

If consumption started growing at 12% real (say 15-16% nominal growth which is a relatively heroic assumption) and gradually edged down to 8% (11-12% nominal) per annum over the next ten years, then investment would have to grow at 0% to rebalance the Chinese economy. And investment growth is currently well above 0%.

So, on the "when" question the answer is the sooner the better. The longer it takes for the rebalancing to start, the more likely that it ends in a crash rather than an orderly transition.

The real question is how much ideological conviction to Chinese politicians have in rebalancing?

While Chinese GDP growth has been impressive, the growth has not been evenly dispersed among Chinese citizens. Estimates of the Gini coefficient, which measures inequality, have grown dramatically in China and suggest that China (ironically for a communist nation) has one of the world’s most unequal wealth distributions.

The inequality creates a number of issues. I am going to ignore the potential for large-scale political upheaval, not because it is unlikely but because human beings have proven to be very poor at predicting regime change and I am unlikely to be any better. It’s a risk that needs to be kept in mind, but there is little an investor can do right now as regimes can last decades beyond expectations or fall within weeks of experts decrying any possibility.

What the imbalances do create is something MB readers are used to reading about and something I am much more comfortable forecasting – political self-interest.

The growth in wealth for a (relatively) small number of people within China has been spectacular and has been based on the existing arrangements where investment growth is high.

Additionally, local governments are highly reliant on land sales to developers. Reports about Chinese party officials owning tens or even hundreds of properties, plus that China does not rate well on most measures of corruption (on the Transparency International 2012 study China was ranked 80th, citing graft, bribery, embezzlement, backdoor deals, nepotism, patronage, and statistical falsification) suggests that the relationship between party officials and developers is unlikely to be entirely above board.

So, rebalancing means less development which then means less chance for lower level communist party officials to “supplement” their income. As rebalancing occurs, it will create (probably quite intense) political pressure for the Chinese leadership.

Does the Chinese leadership have the fortitude to stand up to vested interests?

No one knows – probably not even the Chinese leadership.

What this means for investors is that it is wise to position portfolios for a rebalancing, but to be mindful that as the rebalancing occurs that there will be a risk that leadership will cave to vested interests and begin another round of stimulus.

For Australian investors, we also need to be mindful of the reduction in demand for commodities, see Houses & Holes’ posts here, here and here and here and here. Come to think of it, if you click on any H&H post, you’ll probably see something about this.

What is the end game?

My bet is that China will follow the Japanese path – spend as long as they can, then bundle all of the bad debts up into banks and zombie companies, followed by decades of economic stagnation where the economy goes nowhere but unemployment never gets too high, household incomes keep growing, and the Communist Party stays in power. Add in a rapidly ageing Chinese population and the parallels might be a lot closer than many imagine.

The danger is that they get it wrong and either an economic crisis or a political upheaval occurs.

In the next few years, the effects could easily be overshadowed by our next theme.

Mid-Term Trend 2: Trump tax cuts

The Chinese stimulus following the financial crisis was big. Big enough to mask other economic issues and help the lack of demand for much of the world, not least in Australia.

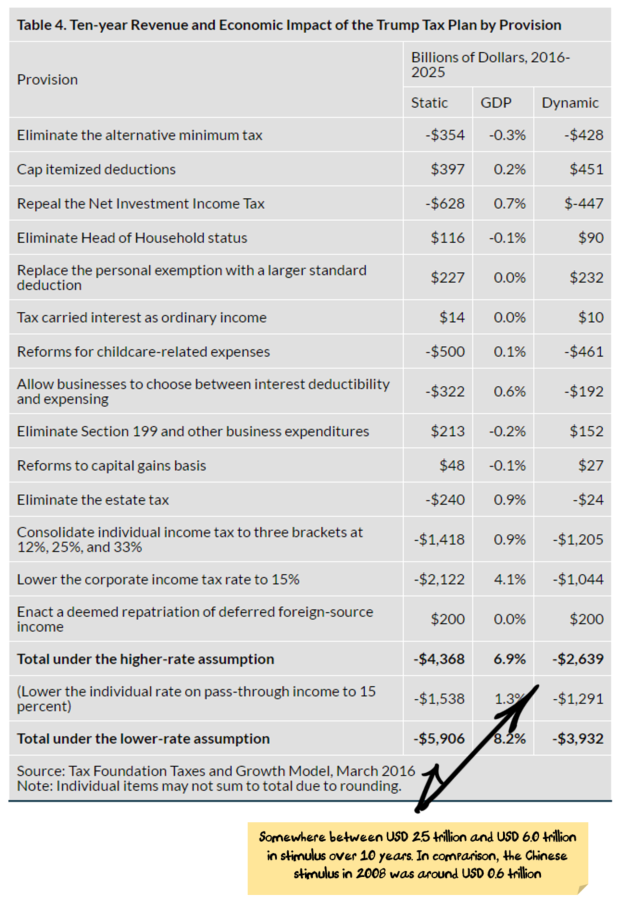

I am thinking that Trump tax cuts could do the same. He has promised tax rates will be cut across the board (top tax rate from 39% to 33%, company tax from 35% to 15%) – and its hard to see a Republican House or Senate standing in the way of that change as they are generally pro-tax cuts.

But keep in mind that there is considerable uncertainty with anything that Trump has said.

Now these tax cuts are badly targeted by giving most of the benefit to the rich and to companies, trickle down is unlikely to work, it's unsustainable, it’s only a short-term sugar hit, I understand all the negatives. But if it is anywhere near Trump’s promise then it’s going to be such a huge stimulus that you don't want to stand in the way of it as an investor.

It is almost as if Trump wants to engineer a boom/bust cycle:

So how do you play this theme?

Round 1: Buy US stocks for the sugar hit, plus exporters in non-trade pact countries

It does look like a huge stimulus package in the US is about to be enacted.

This means that the US will go deep into debt - a good thing for global demand.

This means the end of the rate cycle (although the upswing may not last that long). The US dollar is likely to be strong, and I suspect that the US dollar will offset a lot of the benefit for the US – i.e. US demand increases, but a decent amount of that benefits the rest of the world through increased exports to the US.

In aggregate, this is a buy US equities story, probably go light on US exporters or companies that are import exposed as the US dollar strength is going to hurt them the most. In other markets, try to avoid exporters who will be hit by trade sanctions (Mexico, Canada, China) and look for those that might fly under the radar and benefit from US demand (UK, Europe, maybe even Japan). Increased demand puts a floor under a lot of commodity prices; some will rise.

Keep in mind that some of this is already priced in.

Round 2: Reduced world trade, increased protectionism, Europe splinters

Hello higher costs in the US. Net/net the average Trump voter will probably give back from a higher currency and increased inflation any gains from increased protectionism.

Are we going back to the 1930's?

Will a US/China trade war break out or will it just be lots of noise and posturing while in the background the increased US demand benefits the Chinese economy? Hard to tell, and I’m not willing to decisively invest on this theme until things are clearer. The US House of Reps + Senate are Republican dominated and so are not "naturally" trade protectionists. If Trump's popularity takes a hit then they may become more obstructive.

US companies will struggle with profit growth due to higher costs (with the higher USD), fading stimulus.

Europeans to continue to splinter.

Does Trump have a war in him? Quite possibly... Hopefully it’s not China. Ten years ago, if you suggested that the US might go to war with the Philippines, people would have laughed at you. I’m not saying that I think that a war between the Philippines and the US is likely, but as a sign of the times I wouldn’t rule it out…

Round 3: Unsustainability become apparent

If you don't believe in trickle down (I don't) then at some stage the debt becomes unsustainable and taxes need to be lifted. Hopefully it’s not too close to the time that the Chinese debt becomes unsustainable... Anyway, that is future me's problem - probably 2-3 years away at least, maybe 5 years away, at which time we are in a worse position that today, the core problem of too much inequality/lack of demand still exists (probably gets worse).

Maybe it is the Euro falling apart, maybe it is another external shock, but the core thesis of a lack of demand largely driven by inequality remains and in 3-5 years we are back where we started but with a much higher US debt balance.

So, investors should play the boom but don’t forget about the bust.

Mid-Term Trend 3: Europe falling apart

This post is already longer than I intended, so I'll be brief on this one as the can has been kicked down the road (again) on Europe, and Trump tax cuts increasing world demand could paper over the cracks for a few more years.

There are structural problems with the Euro which have resulted in a depression in Greece and deep recessions in Spain and Portugal. Italy and France are struggling to meet deficit commitments. Germany is doing well (thank you very much). There has been a rise in the support for anti-euro parties in most countries across Europe and Britain has voted to leave.

I’m a subscriber to the Pettis school of thought on this one. Basically, Spain (as a representative of most of southern Europe) did not “pull” savings from diligent, pious German savers; but an underpriced Deutschmark (at the creation of the Euro) and German labour reforms caused a drop in German wages relative to German GDP. This meant German household consumption fell as a proportion of GDP which meant that German savings (being the other side of the coin) rose. These German savings were then “pushed” onto the rest of Europe.

Ordinarily, this would be solved by currencies: the Spanish currency would fall, and the German currency would rise. That way German workers would be wealthier and consume more, and Spaniards would have lower wages and be able to compete with German workers. But these countries are locked into the Euro which means that a different resolution is needed.

The solution to European problems (from Germany’s perspective) is for Spain to stop borrowing the money that German banks keep offering them. Which basically amounts to recessions in Spain until wages in Spain fall low enough for Spanish workers to compete with German workers. The Pettis solution is for Germany to increase wages and spending to create household demand that will allow Spanish workers to compete.

It looks like Europe is going to continue to down the recession route. Which means a rise in voter discord and increased likelihood that Europe falls apart.

Other trends: On the reserves bench

There are lots of other trends that I’m keeping track of, I’ll explore them in more detail later. Each has the potential to be promoted to a key theme:

Trade Imbalances: China, Japan and Germany have traditionally run large export surpluses while the US, Australia, UK and other countries have run large deficits. Over the long-term this is not a sustainable trend, and changes to this have the potential to be disruptive.

Energy Parity: My pet theory that we are heading for energy parity where all forms of energy are (roughly) the same price with solar + batteries being the upper bound on prices. Hard to find winners, easy to find losers.

Driverless Transportation: My take is fourfold: (1) driverless transport is more likely first in constrained, known environments – which is handy because most people live in cities. (2) the cost savings are considerable for taxis/public transport as the biggest costs are the driver (removed) and depreciation (improved utilisation rates). (3) driverless cars increase the speed of electrification of vehicles due to cost and convenience factors. (4) the timing is unclear, but the proliferation of live trials suggest that it is coming sooner rather than later.

Low volatility investing: There is a small bubble here, quite possibly a (minor) blow up coming.

The next phase of monetary policy: Two decades of monetary stimulus in Japan, closing in on one decade in Europe and still few signs of inflation. Something needs to change.

Technological change: Technological changes are always happening, but they do come in waves as computing power gets cheaper and a new group of industries come under threat. Current industries are transport and energy.

Chinese capital flight: If you are a diligent, hardworking mid-level government worker who has managed to save a few million dollars and you are worried about explaining how you managed to save that much while on a salary of a few thousand dollars a month then you need to get that money out of China.

Climate change / green energy: This post is already a little longer than I thought it would be… I’m going to leave this for later.

The Bottom Line

The outlook is a clouded at the moment, largely because of uncertainty about what a Trump presidency will mean.

My base case is that Trump gets the tax cuts through, but his trade war rhetoric is more bark than bite. If the trade wars do break out, then it is an entirely different ball-game and we will need to revisit our investment thesis.

In the meantime, tax cuts of the size Trump is suggesting will be too large for any investor to ignore. If the stimulus is in the current form, it will dominate the economic outlook for the next few years - likely overshadowing most other themes. I'm thinking it results in a classic boom/bust cycle with lots of debt-fueled spending in the short term which stops when the debt gets too high. While I don't like the nature of the stimulus, I don't think it will be good for the US economy in the long term and I think it will result in a (possibly very damaging) bust, you don't go underweight equities in fear of a bust before the boom has started.

Whether right now is the right time to be buying equities and what is priced into markets is a different issue - more on that next time.

January 21, 2017