Putin's carbon tax

A side effect of Russia's invasion of Ukraine has been the jump in oil and gas prices. The result is basically a global Putin carbon tax. Albeit with the proceeds going to Russia and OPEC rather than to national governments. When you add the re-realisation of commodity supply chain instability, there is now an increasing incentive for an express transition away from coal and gas. To a lesser extent, oil is affected.

The cost of Putin's carbon tax

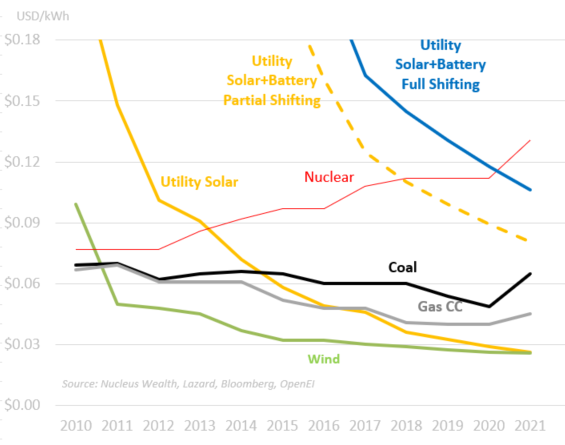

Coal, gas, oil. All have economics based on a scarcity curve: the more we use, the deeper we need to dig and more expensive to extract. Solar and battery power is on a technology curve. The more the world produces, the cheaper it becomes:

This leaves us with an energy parity where the technology curve becomes an upper bound for the scarcity curve. i.e. the price of energy will trend towards the cost of Solar+Batteries.

Solar+Batteries are the "killer app" – extremely scalable once they reach an acceptable cost.

The issue is that gas-fired electricity is extremely sensitive to fuel cost. Even more so than other technologies. At current, elevated European gas prices, renewables + batteries are far cheaper than gas.

What about hydrogen?

Think of hydrogen as a battery. Energy is needed to create hydrogen, which can then deliver energy in the future. The problem is that the roundtrip losses are high. Whatever power you start with, you will lose 55-85% in creating and then burning the hydrogen. Existing batteries lose less than 20%, and the newest technology batteries lose around 5%.

On the other hand, hydrogen storage is much cheaper than batteries. If you double battery storage, then you roughly double the price. For hydrogen, that is not the case. My rough estimate is that hydrogen becomes attractive if you want to store energy for more than three days. Most electricity grid applications do not need to keep energy for that long:

How fast can Europe transition to renewables?

Not particularly quickly. There simply isn't the capacity to produce solar panels or batteries at the scale needed. If world solar panel production grew incredibly quickly, say 30%+ per annum, solar would still only be around 15% of world electricity production by 2030. Even if Europe took half of the increased solar production each year, it would take about five years to be weaned off Russian gas.

With more gas imports from the US, maybe that could be two or three years.

The net effect: Even with Putin's effective carbon tax and considerable political incentive, renewables are probably a decade away from capping energy costs. The economics with current European prices favour a rapid transition. But the capacity is not there.

The effect of Putin's carbon tax on the economics of electric vehicles

Oil has a similar cap to electricity. Electric vehicles. However, while solar+batteries are at price parity, electric cars are more questionable without subsidies. Especially in Europe and Australia.

The economics are similar: pay for a battery up front and then pay far less in fuel. And costs are showing the same technology curve:

Then the problem becomes more complicated:

- Both electricity and oil costs can change. If you thought electricity prices would rise and oil prices would fall, the equation is very different from electricity prices falling and oil prices rising.

- There are meaningful taxes and subsidies for both. Government policy changes the equation from country to country.

- Range anxiety dominates the equation. Electric cars are more economical today for most consumers who are happy to charge every few days. But range anxiety means consumers want a bigger battery that is effectively a wasted investment.

I find the most useful way to look at the equation is in terms of payback. For example, if a battery with a range of 300km costs $6,000 and saves $2,000 per year in fuel costs, the payback is three years.

Note the charts above use retail electricity prices. If consumers use their spare solar power, the economics are dramatically better. For example, Australia would look more like the US:

And finally, at $100 oil, commercial vehicles are no-brainers to switch to electric. In all the above countries, the payback period is slightly more than a year.

Range anxiety calculation aside.

Most cars drive less than 33km per day (12,000km per year). Say consumers were happy with 100km of range, i.e. charging 3-4 times a week. Then, the economics of electric cars stack up today.

But consumers clearly aren't happy with so little range. Basically, consumers want to buy a larger battery to:

- make the occasional longer trip

- ease their range anxiety.

The extra battery capacity is effectively "wasted". i.e. consumers are paying for much larger batteries and rarely ever using the excess capacity.

The question is whether consumers need twice the capacity, five times as much or ten times to be happy. So far, as battery costs come down, electric vehicle manufacturers mostly keep the car's price unchanged and extend the battery range. Which means the economics are not materially changing.

Renewable energy & electric vehicle costs will fall.

Both are on technology curves and have years of further price declines. But, supply chain issues and commodity costs will probably mean not much change for prices in 2022. So, while the above charts will look much better in five years, they may not be measurably different over the next year.

How fast can Europe transition to electric vehicles?

Slowly. First, there isn't the capacity to produce batteries (or cars) at the scale needed. Second, most cars last more than ten years. With electricity, there is an economic imperative for energy companies to switch. Consumers don't have the same imperative. And some of the economic imperative might be absorbed by lower prices in the second-hand car market.

If electric vehicle takeup is substantial, won't that create massive electricity demand which will delay the transition away from gas?

A little. But at the speed we are talking about, it won't make that much difference. Also, car engines are not efficient. Less than 20% of the energy content of oil ends up as mechanical energy. i.e. losses are more than 80%. Losses from batteries are typically less than 10%.

Investment implications

There are no quick fixes for energy. Putin's carbon tax will help accelerate the transition to renewables. Solar+batteries are economically the best option for Europe to transition away from Russian gas, but the capacity to do so quickly is not available.

It is a similar story for electric vehicles. However, the economic pressure is much lower for typical consumers.

Without a rapid expansion of batteries, solar power and electric vehicles, a reliance on Russian gas will continue.