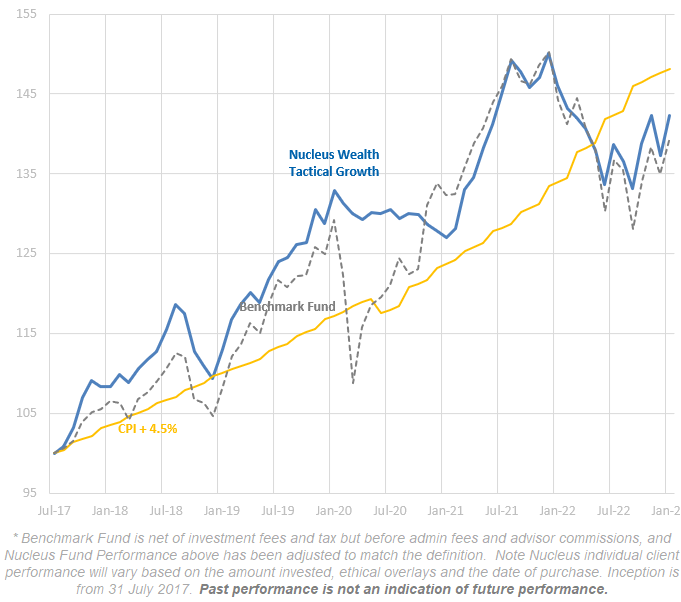

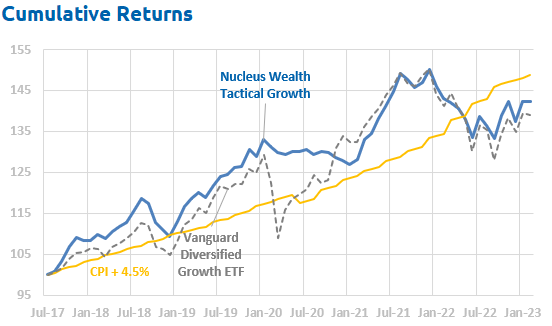

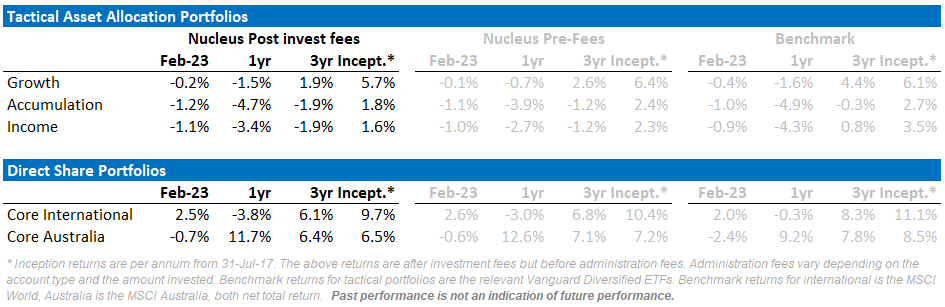

February was a mixed month. The ASX fell in price, down around 3%. Bonds were down around 1.6%. International stocks fell in US dollar terms, but rose 2% after accounting for currency. Given our conservative exposure in both an absolute sense and within equity portfolios this meant our portfolios generally performed better than benchmarks.

We expect weak stock markets as the central banks raise rates to slow demand, shrinking company profits.

With that in mind, the key factor to watch in the coming months to tell if we are wrong or right is the change in corporate profitability. The recent reporting season in the US showed some signs of weakening earnings, but not enough to confirm our thesis yet. Earnings continued to be downgraded over February, but not significantly.

A financial market tug of war

Stock markets are oscillating between hope and resignation. The hopeful side has two different, quite distinct strains. The bearish arguments are more about the degree of pessimism. But first, some background.

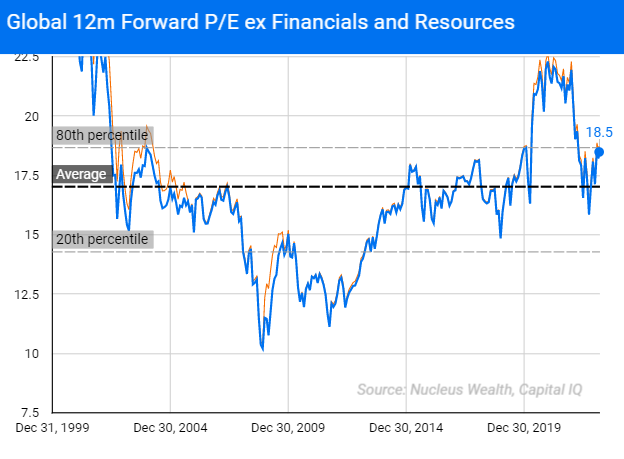

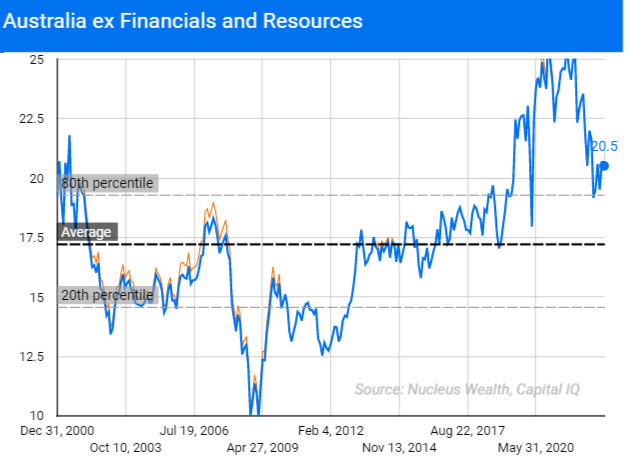

Global markets (excluding banks and resources) are on a forward earnings multiple of around 18.5x. i.e. stocks are, on average, 18.5x higher than the earnings which back them.

This is higher in the US and Australia and lower in Europe and Japan. Vs history, it is at the 80th percentile (i.e. expensive):

Earnings have fallen about 10% so far. Typical indicators suggest there is a lot more downside. But analyst forecasts are holding up. In the last month or so, forecasts have been resilient. Optimists are suggesting that earnings forecasts have bottomed.

Bullish argument 1: Bad news is good news

A return to 2021 conditions. Bad economic data means that bond yields will fall, central banks will reverse course, flood the market with liquidity and earnings multiples will expand.

This argument is basically:

- Earnings forecasts won’t fall much further

- Falling yields will mean that the amount investors pay for assets will increase.

Say earnings fall by less than 5%, and markets return to post-pandemic multiple highs of 22.5x. This would imply 10-15% upside to stock markets from here.

In my view, this is not rational. High earnings multiples come from excitement about earnings growth, not relief about the lack of downside. Markets can be irrational. But investing because you expect markets to become less rational is rarely a winning strategy.

The days where bond yields fall and the tech sector rises are the days where this narrative is the winning one.

Bullish argument 2: a soft landing

This argument is that the Fed has done a masterful job, and inflation will ease back into range while employment edges lower.

This argument is basically:

- Earnings forecasts have bottomed and will start to rise, outpacing inflation

- The multiple paid might ease lower, but higher earnings will mask any weakness.

Say earnings rise by 10%, and markets trade roughly on current multiples. Including dividends and buybacks, there could again be 10-15% upside to stock markets from here.

I’m not going to say that a soft landing can’t happen. It is just that soft landings are extremely rare. And even the rare ones usually rely on an external factor to rescue the economic cycle. A deus ex-machina.

If a gift from the gods is what you expect, then this scenario makes sense. In the face of gas shortages, the incredibly warm winter in Europe counts as one gift. This scenario could make sense if more of these events are coming.

But investing on the hope that something will turn up is not my favoured strategy. To put it mildly.

Bearish argument 1: central banks will do what they say they are going to

Don’t fight the Fed is an investment mantra. It indicates that when the US central bank (the Fed) is raising rates, it is bad for markets and vice versa. The Fed is raising rates. The chair is indicating that interest rates will be higher for longer to cure inflation. If that means a recession, he says that price will be paid.

Market pricing at the moment is that markets do not believe central banks. They are pricing that the economy will go into recession by the second half of the year, and central banks will quickly reverse course.

This leaves us with a simple bearish argument. What if the Fed does what it says it will do?

Typical recessions see earnings down around 20%. Earnings multiples bottom at about 12 or 13x. That implies a 50% downside from here. Welp. Even a mildish recession suggests 30% downside to equity prices.

Is this likely? Probably not. Is it possible? Sure.

So, not a base case but a risk case.

Bearish argument 2: central banks cause a recession and then reverse

Bond markets are already pricing this as the most likely outcome. We concur but note the high level of uncertainty.

The big issue here is the level of earnings downgrades. If earnings downgrades are limited to 5-10%, then prices are less likely to fall dramatically. If investors can “see the other side” of the economic recession, then maybe earnings multiples can stay at elevated levels. i.e. investors will acknowledge the negative earnings but look forward to the growth that follows every downturn. Meaning only 5-10% downside for markets.

But, it is a slippery slope. The further earnings fall, and the less responsive central banks are, the further away the recovery is. So stock markets will fall quickly as both earnings and pricing multiples are downgraded.

Net Effect

Over the past 20 years, developed market economies have become financialised. Both housing and stock markets make up an ever greater proportion of consumer wealth. Increasing values means consumers spend more. But it can also go in reverse. Arguably, central banks have become bubble managers, responsible for injecting confidence into markets.

With the feedback loop between asset markets and consumer spending, it becomes reflexive: rising confidence increases asset prices which therefore increases consumer spending, justifying the prior rise in asset prices. The key central bank responsibility? Making sure the system doesn’t go into reverse.

There is an elevated level of uncertainty at the moment. Investors, economists, central banks, consumers, and corporates are all struggling to come to terms with how to interpret the economy:

- Central banks are trying to guide to higher rates for longer. Markets have been, to a certain extent, ignoring what central banks are saying. The US central bank releases a “dot plot” showing that they expect rates to be over 5% by the end of 2023. In contrast, markets are pricing in rate cuts in the second half of the year.

- Economists are mostly expecting a recession for developed markets. Strategists are calling for earnings to fall 10% or more. Individual stock analysts are largely ignoring both. They are still expecting positive earnings growth from companies.

- The US central bank GDP forecast confidence interval ranges between a recessionary -1% and a booming 3%+ growth.

- Forward indicators from business surveys are at recessionary levels, suggesting a tough ride ahead. In contrast, companies are still hiring. Unemployment rates are at generational lows in a number of countries.

It is no wonder that markets are confused, oscillating between fear and elation.

The bearish arguments make more sense to us. However, uncertainty is high. A slippery slope of feedback loops could quickly turn a mild bearish argument into a devastatingly bad one. Equally, a string of better-than-expected outcomes could turn a mild bearish view into a bullish one.

It is prudent to stay invested for the most likely outcome but be prepared to change.

China Addendum

Australia is expensive:

In our view, most of this is pricing a roaring Chinese recovery. This has yet to occur. The expected wave of stimulus and property development has yet to happen.

It may still occur.

But markets are already pricing a healthy property market recovery. If the current situation continues, the Australian stock market is significantly more at risk than other markets.

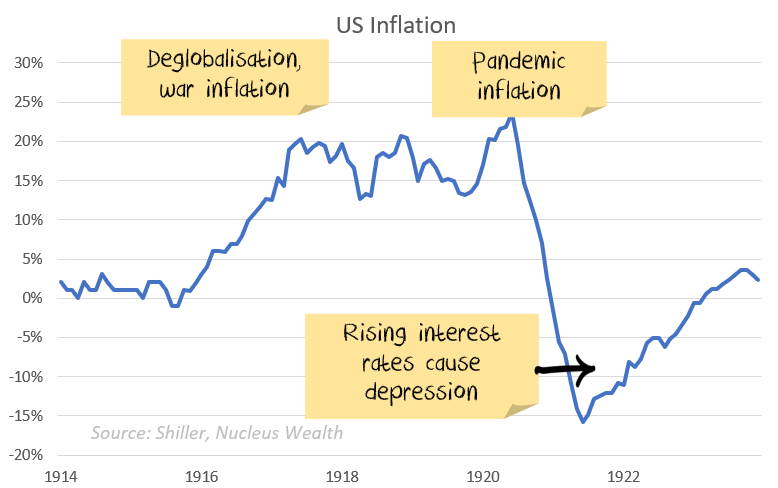

Have we seen this all before?

- Globalised supply chains reversing into more local production due to geopolitical tensions

- A pandemic disrupting supply chains

- A surge in inflation due to supply issues

- Central banks hiking rates into a supply-side shock

Yes, we have. Following World War I, all of the above factors were in place.

By 1920, inflation in the US was running at 15%. The US central bank hiked rates from 3.5% to 5.6% to curb demand. By 1921 the US was in a depression, with inflation of -10%.

The analogy is not exactly the same. But, trying to use interest rates to solve supply chain problems is at the core. There are more similarities than there are differences.

Investment Outlook

I have some pretty clear ideas about which trends are sustainable and which ones aren’t in the long term. However, the short-term is far less clear:

- The sanctions on Russia are unlikely to be lifted anytime soon. The short-term effect was commodity shortages. In the longer term, it seems likely that we will see a re-orientation, Russia will supply more to countries like China and India, less to Europe. For some commodities (oil, wheat) this will be easier. For others (gas) it will be extremely difficult.

- The Omicron variant looks to be resolving in the direction we expected, ripping through economies without too much harm and leaving behind an acceptance that COVID is endemic. In China, rolling lockdowns have finally finished.

- The geopolitical energy crisis in Europe has eased on the back of much warmer weather. Australian energy price caps have pushed down energy prices. There will be a rush to alternative energy sources in the mid-term.

- Supply chains continue to improve.

- Governments continue to withdraw (or not replace) stimulus. There will be a fiscal shock into 2023. The question is whether the private economy will be strong enough to withstand it. Leading indicators suggest profits will be lower.

- Central banks have made it clear that they will try to solve the Russian-induced energy issues and supply chain-induced inflation by raising interest rates. The odds of a policy error have increased significantly.

- China still has not bailed out the property sector. The latest changes are not a bailout… but they may morph into one. China is trying to ensure that houses under construction get built, small businesses have access to credit, infrastructure building continues, and failing developers do not crash the economy. China is yet to show any signs of turning back to the old days of debt-driven property developer excesses. In the short term, commodities have been booming. If China doesn’t continue to roll out new measures, the commodity market will deflate again.

It is still not the time for intransigence. Events are still moving quickly. But we have positioned the portfolio towards the most likely outcome and are gradually increasing the weights as more data arrives.

Bond yields have risen significantly. If the world heads for a recession this is a buying opportunity. In the short term the narrative “high inflation, central banks raising rates = sell bonds” seems to be coming to an end. Although there may be another last hurrah as the US central bank looks to rein in the stock market optimism.

And the mix of higher volatility, leading to deleveraging of risk parity trades and momentum means yields could yet go higher. We are invested for bond yields to reverse.

Asset allocation

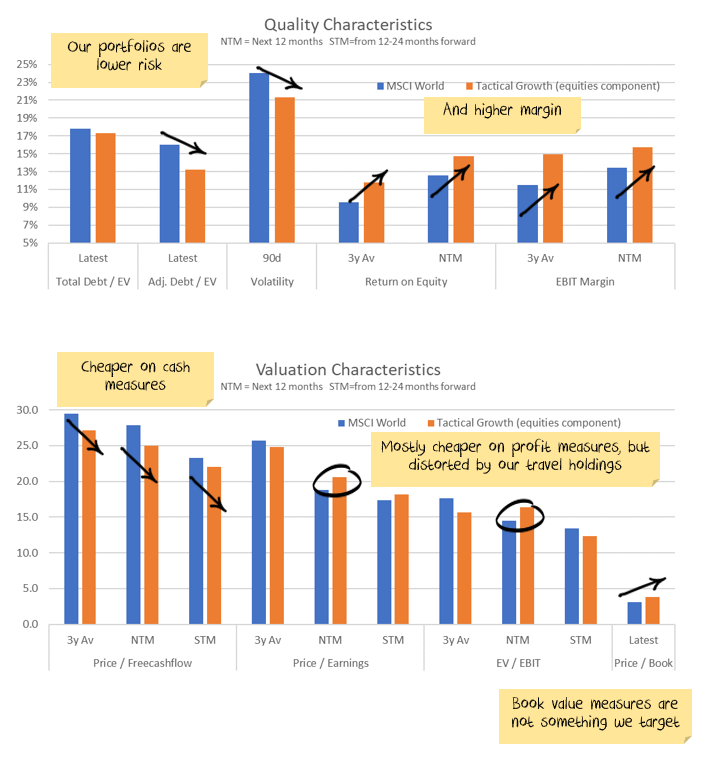

After being very expensive for a number of years, stock markets are now merely expensive. Debt levels are extremely high. Earnings growth had been really strong but has come to a halt. There are signs it is starting to reverse.

Markets are supported to a great degree by central banks and governments. Policy error is every investor’s number one risk.

But, any number of other factors could force this off course and see unexpected inflation. COVID mutations could disrupt supply chains again. Chinese/developed world tensions might rise further, leading to more tariffs. Or, China might reverse its tightening on property sectors.

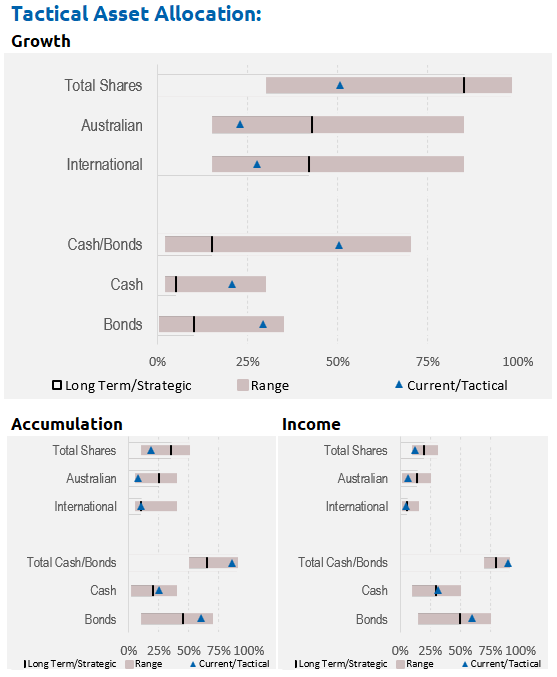

We are significantly underweight Australian shares, and as noted above, overweight bonds, with the view that the Australian market is more quickly affected by rising interest rates and more affected by a global recession:

Performance Detail

Core International Performance

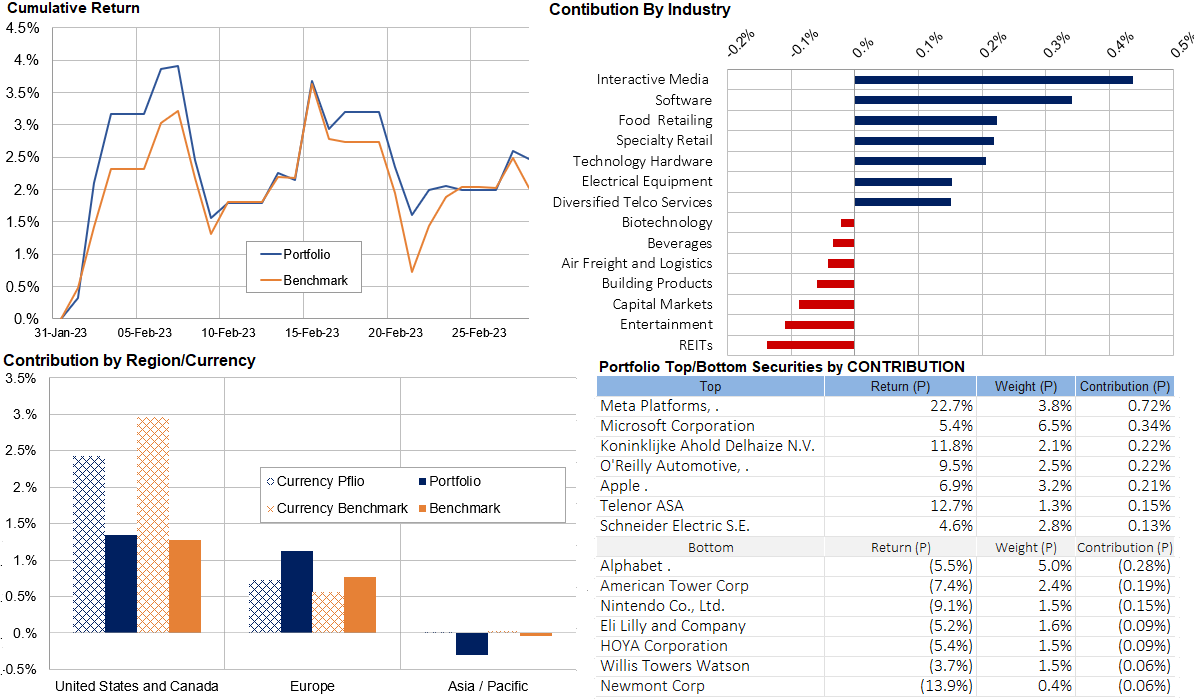

February was back to risk-off for international stocks in US dollar terms. However, aided by a falling Australian dollar our international portfolio finished the month up 2.5%. While the currency was a key contributor our stock selections in local currency terms outperformed everywhere but Asia/Pacific. Defensives and a continued recovery in Meta boosted performance. Alphabet (Google) and American Tower Corp provided the biggest drag on performance.

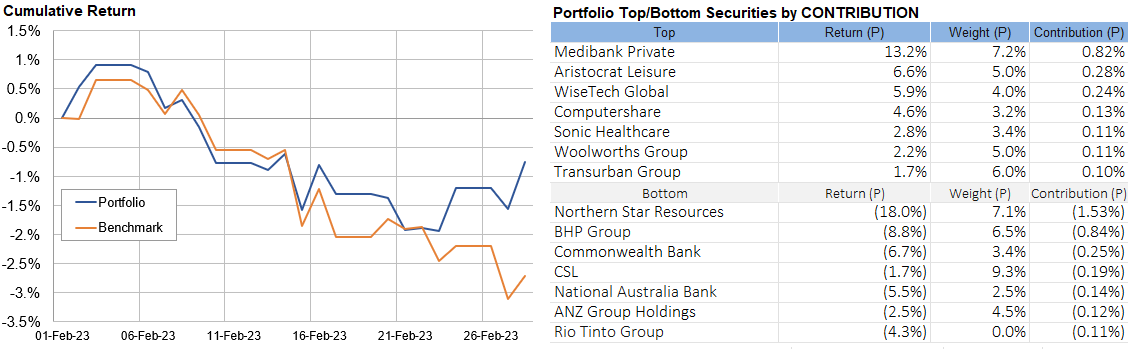

Core Australia Performance

Australian indices fell significantly over the month led by the bank stocks in particular. Being significantly underweight banks and resources meant that our Australian portfolio outperformed in the falling market.