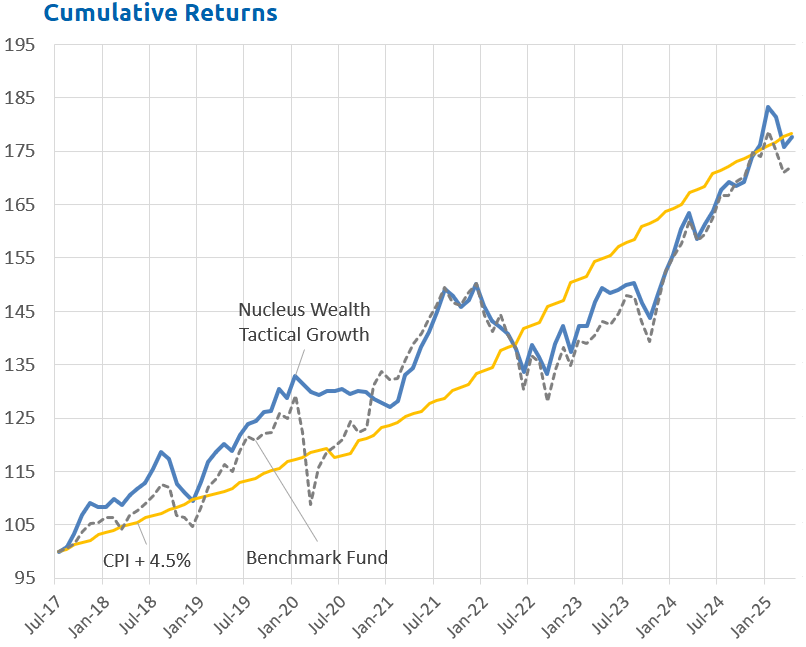

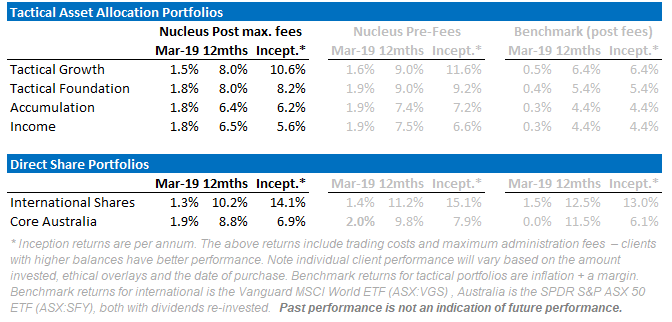

March 2019 Performance

Global equities finished the month with the best quarterly performance since 3Q 2010. Of more interest to our investors though: we have had a change of heart and made some significant portfolio changes. Our assessment is that "we are not in Kansas anymore" and, while we will return to the real world before the end of the movie, the investing environment for the next 6 to 18 months needs a different asset exposure.

In March, the rise in global equities wasn't as sharp as January/February’s optimism over increased central bank dovishness gave way to worries over global growth slowdown, U.S. yield curve inversion, and looming recession concerns. In particular, we are seeing a divergence between bonds, which are pricing a slowdown, and equities which are pricing renewed growth - which in the end meant that asset allocation was less important as both bonds and equities were rising in price.

We have been arguing the overweight bond case for six months now, but we are putting that view on hold. Not over the longer term, we still believe secular stagnation, low inflation, low wage growth and an overly stubborn Reserve Bank of Australia will drive Australian bond yields lower. However, for the next 6 to 18 months we believe the debt push in China will provide a burst of growth that needs to be recognised in our investment positioning.

A long term trend

Our core thesis over the past ten years has been that China's growth is, in the words of its own Premier, unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable. China is running a Gerschenkron economic growth model, which has been run by many countries in the last 50 years including Russia, Japan, South Korea and a number of Latin American countries. The model works like this:

- By repressing consumption China increased their savings rate

- This savings was diverted into investment

- Most of the investment was centrally managed infrastructure spending (as the private sector is not good at that kind of investment)

- China also kept interest rates low (below inflation for many years) which penalized savers and benefitted companies and governments

- At first, the investment earned great returns (as China was in dire need of investment) and was hugely successful at increasing wealth for everyone

- As time went on, the investment projects generated lower and lower returns

- Finally, the return on investment fell below the return on debt and the debt burden began to grow

- At this point, you would think that a new growth model would need to be created – but in every other country that has followed this growth model, they have stuck to the old growth model and kept increasing the debt until some form of crisis forced a change.

China spends around 50% of its GDP on capital expenditure, mostly housing and infrastructure, which is far in excess of other countries, even those like Japan or South Korea that followed a similar growth model.

So, our view is that China will structurally try to manage away from this growth model as the debt burden required to maintain that model increases every year.

However, vested interests made a fortune from the rise of China, and they don’t want the party to stop. More bridges, more apartments, more airports and more train lines. China’s growth model was unsustainable in 2010 and is less sustainable now. But there is still scope for the model to be pursued for a considerable period of time – with less and less of an effect every year.

We expect Chinese growth to grind lower, where minor measures will be attempted to improve growth (with little effect) until growth slows enough or vested interest bleating becomes loud enough for another round of stimulus.

An echo boom

It seems clear now that the spectre of a US/China trade war, combined with slowing growth both in China and globally has been enough to spark another round of debt stimulus in China:

To be frank, we thought the January stimulus was partly due to timing issues with Chinese New Year and catch up for the winter shutdowns. The decline in non-bank loans in February re-inforced that view. But March data makes our view from earlier this year look wrong. It’s too early to know for sure, and Chinese authorities may turn this off just as suddenly if there is a trade deal, but for the moment we are treating this as a fundamental change.

Effect on Australia

The main transmission mechanism from Chinese growth to Australian growth is through commodity prices - mainly iron ore, coal and gas. Chinese home building is the largest source of demand for iron ore and coking coal - Australia's largest exports. Also, Australian corporate profits increase, government royalties and tax receipts improve the government budget, the improved budget often triggers tax cuts, and higher commodity prices spark increased capital expenditure. These episodes also often coincide with a rising Australian dollar.

But we do think things will be somewhat different this time.

There is recognition in China that the rate of change of people moving to cities has declined - i.e there are still a lot of people moving to cities, but the number moving each year is declining:

The Chinese stimulus currently looks more targetted than prior lending booms so as not to add to the problem. i.e. the focus is on avoiding too much more homebuilding.

However, increases in lending are a blunt instrument - we fully expect a chunk of the increased lending to end up in the Chinese housing construction market:

The differences between this time and the prior episodes are:

- Less focus on home building

- Iron ore prices are already high due to a supply shock driven by the removal of Brazilian iron ore after two dam collapses in Brazil. We expect that the increased demand from China will be partly offset by the return of Brazilian production, which will limit the iron ore price.

- China's iron ore demand is largely expected to have peaked, which will limit the number of new mines and mine expansions built in Australia.

- Australian thermal coal has been targetted by China for political reasons and so the price has been falling for the past six months. While the political situation could reverse quickly, on current trends it limits the transmission of Chinese growth into Australian growth.

- There is usually a lag between when commodity prices affect tax revenue to the actual tax cuts of at least 6-12 months. Given Australia is having a Federal Election on 18 May, there may well be an amount of any budget benefit delayed for the next election. Also, state governments budgets are in the middle of being devasted by falling property transactions, limiting the net effect of federal plus state government spending

- The China/US trade negotiations are believed to include some energy provisions - i.e. Australian gas exports might be offset by increased US gas exports. Regardless, the poor structure of Australia's gas royalties means that even as Australia becomes the largest exporter of gas in the world very little will flow through to governments as royalties.

The aggregate of these factors means that while the effect will be positive for Australian growth, just not as large as prior episodes. The initial Chinese debt boom had the largest effect on Australian growth but each subsequent echo boom is having less and less of an impact.

March Quarter International Exposures

The attribution charts of our International portfolio shows the greatest contribution (blue bars) came via the various technology sectors recovering from December lows, though the best overall performer in the quarter was our energy exposure. Geographically Europe and US stocks saw similar performance with Japan/Asia the laggard.

Given the March quarter proved a virtual retracement of the Dec quarter, we thought it interesting to breakdown at the two past quarterly performances. The Chart below shows their relative contributions to our International portfolio returns for the past 6 months. While Technology stocks saw the greatest swings, it was the Energy, Finance and Health sectors that saw the best net performance on a 6 month view. Europe surprisingly saw a better recovery than the US.

Tactical Asset Allocation Portfolio Positioning

In our tactical portfolios, we own cash, bonds, international shares and Australian shares. We tend to blend these portfolios for clients so that each investor receives an exposure tailored to their own risk and income requirements.

The broad sweep of our asset allocation over the last 18 months was to ride the Trump Boom, winding back on equities as share markets advanced and topping up when they fell but maintaining an underweight overall position in shares. For the past six months we have been very conservative with our holdings, looking for an appropriate level of protection as the current business cycle draws to a close. The increasing Chinese debt is enough for us to reconsider our view. If the business cycle is extended for an additional six to twelve months then there is scope for us to take more risk. We have:

- reduced our bond overweights

- begun to redeploy our cash into select equities positions. In particular we see value in Europe.

Over / Underweight positions by portfolio

Epilogue

Both Australia and China have imbalances that will eventually be resolved. The influx of another round of Chinese stimulus will delay the resolution for both countries, and make the eventual resolution more problematic. However, in the short term, we expect the impact of the latest round of Chinese stimulus to be similar to prior episodes. This more positive outlook hasn't been enough to convince us to significantly change our weight to Australian shares - Australian shares are still considerably more expensive than most international comparisons with poorer growth expected.

We retain large cash and bond balances to hedge against volatility and in the expectation that capital protection will be important during 2019. Our key focus is Chinese growth, gauging the extent of the slow down and the policy response.

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at Nucleus Wealth.

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen is an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management, a Corporate Authorised Representative of Integrity Private Wealth Pty Ltd, AFSL 436298.