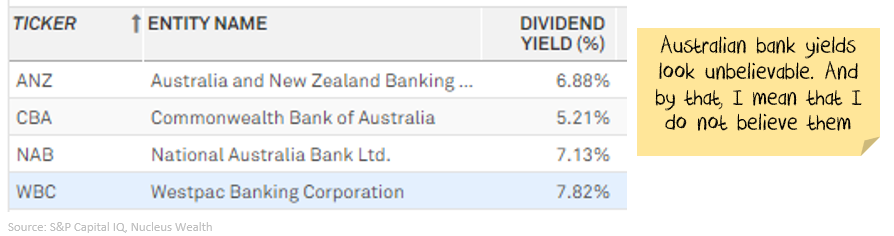

Australian Bank dividend yields are unbelievable. And not in a good way.

Don't be fooled by the dividend yields that you might see for the major Australian banks. They are reflecting a rosy vision of the future that is far from certain, and in my view are a value trap.

For those with superannuation investments (where Australian bank shares make up a large part of most funds), investments or a home loan, it is important to understand the fundamentals of the banking industry.

To me, there are three significant risks to an investment in banks :

- Global pandemic smashes demand and consumer confidence

- Supply-side problems in China mean indebted companies start going bankrupt, and contagion spreads

- Demand problems from global travel restrictions mean companies stop spending on capital expenditure

I've explained the risks a few times in the last week with these outcomes and will no doubt do so again. So I won't go into that again today.

What I want to deal with is even if none of the above occurs, then Australian banks still have another big hurdle to jump:

If interest rates stay stuck at low levels, then profitability will be eroded

Economics of lower interest rates

The general theory is the Reserve Bank of Australia wants to get more economic activity to decrease unemployment and lift inflation. By lowering the interest rate:

- Consumers with home loans save money. For a small proportion, this means that they can afford higher house prices and so bid up the value of existing houses. For other consumers with home loans, the cost savings and the confidence from higher house prices translate into greater consumption spending.

- It becomes cheaper for businesses to borrow to invest. The mix of more consumer spending and less expensive loans means that more firms invest.

The combination of the two is a virtuous circle that then employs more people, which creates more consumption and more business investment and so on.

However, these are reliant on the expectation:

- banks will lend more money as interest rates fall.

- consumers will be confident enough to take out the loans

- businesses will be confident enough to take out loans and expand

Bank Business Model

The problem is banks have different incentives in their business model: low-interest rates are not necessarily better. If interest rates are too low, it can be a disincentive for banks to lend. As we have seen in both Europe and Japan.

At the simplest level, banks are an asset/liability mismatch. In essence, banks borrow from depositors (and others) on a short term basis and lend it out for long periods.

So, banks make the most money when short term rates are low (borrowing is cheap) and long term rates are high (lending is expensive). This is called a steep yield curve. The actual level of interest is far less important than the difference between the two interest rates.

But, as many depositors know, banks stopped paying interest on most transaction accounts a few years ago. So banks can't lower interest rates on those accounts any further to reduce costs. This means lower rates don't decrease bank costs for at least part of a bank's liabilities.

The other part of a bank's liabilities is more complicated. The short version of the story is yield curves are very "flat" (rather than the profitable steep curves), and so there isn't much relief on that front either.

The net effect: rates cuts for banks are going to eat into profitability.

Europe has been facing this conundrum for years. How do central banks keep rates low enough to stimulate the economy but not send the banks bankrupt?

And that is where Australia now finds itself.

Investment Outcomes

The three main investment factors are that Australian banks:

- Earn some of the highest returns on equity in the world

- Are some of the most expensive banks in the world

- Look attractive from a yield perspective as interest rates march lower

The optimists suggest:

- You pay up for quality

- After brushing off the Royal Commission, Australian banks are through the worst

- The housing market is now rising in Sydney and Melbourne, reducing the chance of bad debts

- Clearly, the government is ready to roll out more policies to support the housing market and grow credit quickly

- Coronavirus will pass quickly, and the world will bounce back in a "V" shaped recovery.

The pessimists suggest:

- As interest rates in Australia chase the rest of the world downward, returns will do the same

- If returns fall any further, then dividends will be cut

- The housing market is vulnerable – the government and regulators used most of their bullets trying to hold house prices at high levels. Now that we have an external shock, the tools to support the market are limited.

- There is still a rogue agency (ASIC) trying to litigate against the banks and actually enforce the Royal Commission findings. This could restrict credit once more.

- Forward indicators of construction have cratered. And there is a gap in the infrastructure pipeline over the next few years. And the bushfire effect on tourism. And the coronavirus effect on almost everything. We saw in Western Australia over the last five years that rising unemployment trumps easy credit.

How far can dividends fall?

Our View

In our superannuation and investment funds, we are very much erring on the side of caution.

First, I do think that at least one of the major risks is likely to occur. But, even if banks dodge all three, then the low interest rates forever are going to strangle bank returns. And Australian banks are still not cheap! Relative to other banks around the world, the Australian banks are some of the most expensive.

In our portfolios, we have been underweight banks for some time as we expect interest rates to remain low for years. Then, at the end of January we: (a) moved our tactical portfolios into cash & bonds (b) reduced our bank holdings to minimum weight. We have no interest in owning banks going into a likely debt crisis.

Make no mistake: right now, an investment in the banking sector is a macro-economic call. If you want to buy the banks on your expectation of a favourable macroeconomic outlook, then I can understand that view. But given all the risks, don't get starry-eyed over a dividend yield that is far less certain than at any time in the past decade.