Commodity super-cycle hype: Copper edition

Over the last few months, there has been an increase in analysts calling a commodity super-cycle. I disagree. Many commodity prices are at super-cycle levels. It is the volumes that are not in a super-cycle.

And high prices without an increase in volumes is a sure recipe for price reversion. Or, in other words, a cycle. Not everything needs to be super.

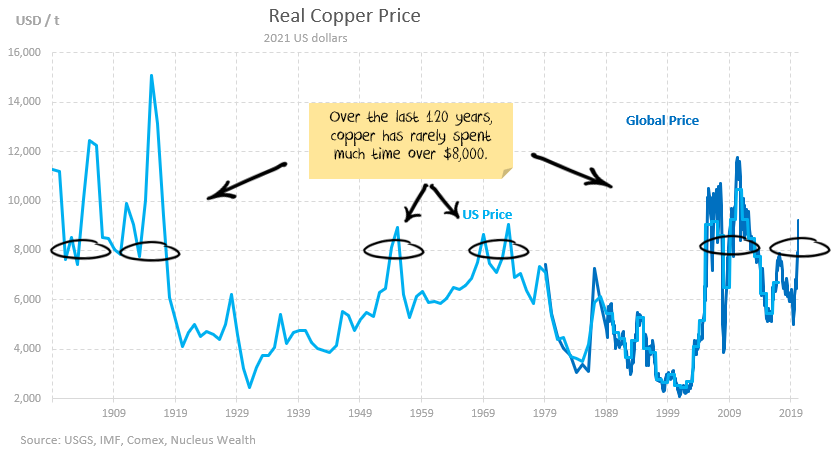

Take copper, for example. Looking at a 100-year chart adjusted for inflation, it is clear that prices above USD8,000/ton are the exception, not the rule.

This recent Bloomberg post is typical of the hype. Titled "China's Commodities Binge Makes America's Future More Expensive", it launches into a description of all of the shortages:

America requires steel, cement, and tarmac for roads and bridges, and cobalt, lithium, and rare earths for batteries. Above all, it needs copper—and lots of it. Copper will go into the electric vehicles that President Biden has said he'll buy for the government fleet, in the charging stations to power them, and in the cables connecting new wind turbines and solar farms to the grid. But when it comes to these commodities—and copper in particular—Washington is one step behind Beijing.

...

Chinese entities, many of them state-owned, have bought mining operations everywhere from the Democratic Republic of Congo and Peru to Indonesia and Australia. In recent years, they've also been buying up international trading companies.

Bloomberg makes the copper situation sound scarier than the reality.

The US infrastructure boom is over-hyped

Bloomberg inadvertently destroys their own argument at the end of the article:

While the details of Biden's infrastructure push remain to be haggled over in Congress, consultancy CRU Group estimates that $1 trillion of spending could necessitate an additional 6 million tons of steel, 110,000 tons of copper, and 140,000 tons of aluminum annually.

So, 110,000 tons per annum needed. There are about 30m tons of copper supply per year. i.e. a 0.3% per year increase in global supply. A US infrastructure boom is simply not that copper intensive.

The Electric Vehicle boom impact on copper is over-hyped

A battery-electric vehicle uses around 35kg more copper than an internal combustion engine vehicle. There are about 100m cars produced annually.

So, if the entire world's production changed to be electric tomorrow, we would need 3.5m tons per year, or 12% more copper production.

But it isn't changing in one year. If it takes ten years, then we need 1.1% more copper per year. A solid source of demand. But nothing like the doubling of production we saw from 1995 to 2016.

Secondly, the amount of extra energy needed is not that much. So electric cars don't automatically mean an extensive grid build-out:

Driverless Electric Vehicles could signal copper demand destruction

If and when driverless electric taxis finally go mainstream, the demand for car production could fall significantly.

The average taxi is used between five and ten times more than the average car.

There are complicating factors like vehicle life. And seldom-used cars would be replaced first. But total production is clearly lower.

If three seldom-used cars were scrapped for each driverless taxi, then the amount of copper needed by the auto industry would actually shrink. Which is in the realm of possibility.

The Renewable Energy boom effect on copper is unclear.

I'm a big believer that solar and battery costs will continue to fall and be a critical part of the grid (see here for more):

But there are two ways this can go:

- Centralisation and national networks: This assumes new sources of energy are plugged into the existing national grids. New connections will require a considerable amount of copper. Recycling copper from shutdown sources may offset this a little. Overall, strong demand growth for copper.

- Decentralisation and local networks: If energy storage cost issues are solved, then the need for a national grid disappears. Suppose local networks with storage for thousands of households become the predominant network. There will be much less copper needed. And maybe largely covered by recycling parts of the old national grid that is no longer needed.

The first way seems more likely at the moment as it is the incumbent system. But, the economics will lean more to the second way the better batteries become.

Chinese construction is key to any super-cycle.

The average apartment uses about 150kg of copper. So, build one less apartment, and you can convert four electric cars with the copper saved.

In China, the floor space under construction suggests around 80-90m homes are currently under construction. i.e. one in six Chinese households is having a new home built right now.

Plus, going forward, we expect China to gradually increase the amount of copper recycling, lowering the need for copper from mines.

Could an increase in Chinese copper recycling and slowing construction offset some of the new copper needed? Almost definitely. Could it offset all of the new copper needed? Possibly.

Mine supply has been limited by COVID

Mine production doubled between 1995 and 2016, but since then has been essentially unchanged at around 20m tons per year.

COVID restrictions limited supply from mines in 2020. Production was down around 2% globally vs 2019.

Recycling mistakes in China also hit supply

Global copper recycling is around 10m tons per year.

In 2020, COVID significantly impacted eWaste recycling. Particularly in Europe.

More importantly, China put restrictions on imports of all recycling materials in 2018 as a fight against pollution. This had the unintended consequence of increases the demand for raw copper, which is much more energy-intensive. So, after making this mistake, China has now largely reversed the policy. It reclassified copper scrap as a resource rather than waste and suspended copper import taxes created as part of the US trade war. Copper recycling in China will increase.

The net effect

The copper price is in a super-cycle. I'm unconvinced that copper demand is.

What is more likely is that this is simply a normal cycle:

- Current high copper prices will spark a supply boom (Chile, the world's largest producer, already expects to increase production 20%+).

- The effect will bring prices back to a more normal level.

- Copper miners will make super profits in the meantime, but don't expect the profits to last forever.

- Production will need to increase for new sources of demand, but the growth will be much lower than the growth in the early 2000s.

And, if you are an investor in copper stocks, worry more about Chinese construction than electric vehicle demand.

Not every cycle has to be a super-cycle.

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at Nucleus Wealth.

Follow @DamienKlassen on Twitter or Linked In

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen is an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management, a Corporate Authorised Representative of Nucleus Advice Pty Ltd - AFSL 515796.