Inflation Update

We covered inflation in a lot of detail in our four-part series earlier this year. So far, the inflation cycle is playing out largely as foreshadowed. In particular, the inventory supercycle.

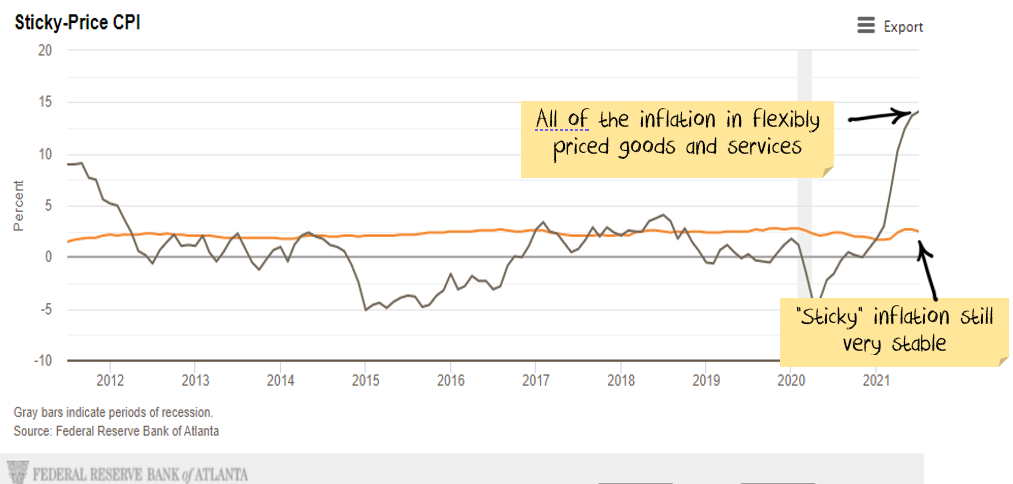

Inflation is still elevated, but the sub-components where we are seeing inflation are not the types of categories where entrenched inflation shows up:

Commodity inflation is peaking

It is not a commodity supercycle. Those last a decade. It is an inventory supercycle. Inventory cycles are lucky to last ten months. Many commodities are showing signs that the inventory supercycle has finished. Iron ore, copper, oil, all have rolled over in recent weeks. Lumber, after trebling, has returned to its pre-cycle prices:

Even some agricultural goods are showing the same trend:

We also covered commodities recently in more detail in The shortest commodity supercycle ever? - highlighting that not only China but macro and micro conditions are ominous for commodities.

Finally, if you don't believe me, then listen to this guy from Twitter a few months ago:

Chinese PPI: headlines look wild, details look tame

In China, consumer price inflation is subdued at 1%. But producer price inflation is booming, up 9% over the last year leading some to suggest China will be exporting inflation soon.

Bollocks.

The components of PPI show extraordinary conditions. 30-50% increases in commodity industries on the back of price rises over the last year, lowflation and deflation elsewhere:

Inflation means continued price rises. If the only source of producer inflation was commodities, and commodities are now falling, what will producer prices do?

Where might we be wrong?

If we are wrong, then wage growth will be where inflation shows up. Wage growth could spark a round of wage-push inflation, where higher wages increase inflation, and so workers demand wage rises to keep up and so on. But "could" is the operative word.

Internationally, wage growth is starting to show. UK wage growth is back to pre-pandemic levels. US wage growth as well:

The difficulty unentangling temporary vs structural issues

The interesting factor is that wage growth is very high in low paid roles that were disrupted the most by the pandemic:

Is it possible that employees in these roles are demanding higher wages to cater for the uncertainty? More consistent work in other industries with a lower risk of being sent home with no pay suddenly looks more attractive than low wages in hospitality.

The problem is untangling structural changes from temporary ones. If there is a one-off shift upwards to cater for the uncertainty, then inflation won’t ensue. And potentially, wage growth will drift lower as the next generation of youths without the memory of losing work at a moments notice enters the workforce.

Job ads vs unemployment indicate a structural change

There has clearly been a structural change in the workforce. One way to see this effect is to look at the number of job ads vs the unemployment rate. The financial crisis saw the relationship take a big step up and to the right:

There has clearly been an even larger structural change due to COVID. However, some of that change is likely temporary. Airlines, restaurants and tourism are all likely to need to hire back staff. The manufacturing sector boomed, with consumers diverting the money they would have spent on services to goods. But this is reversing now and will likely continue to reverse once economies open.

My expectation is that there will be structural changes. There will be sectors that will never return to pre-pandemic levels. But most of the differences are temporary.

Are older workers gone for good?

Another factor is the loss of older workers. Most recessions see these workers leave the workforce and never return. The pandemic so far is showing the same trend, with the participation rate for over 55s down significantly:

What are the other reasons for not working?

There are some surprisingly large differences between Australia and the US over the reason for not working:

However, it is also clear that there is no single reason which will drive participation up. If these workers eventually return they will put more downward pressure on wage growth.

Other factors affecting wage growth in Australia

- Cognitive dissonance on behalf of Australian governments. Public sector wages recently hit a record low. Governments are the nation’s largest employers – higher/lower wages will affect the rest of the market.

- While wage growth expectations have increased recently from economists and unions, households are still expecting record low wage increases. Businesses will likely be keen to meet this expectation...

- Work from home opens up companies to employing people in lower-cost regions. Including international. Basically, it flattens the supply curve for workers (in some industries), keeping wage growth low.

- After years of running massive levels of immigration, COVID has crashed immigration levels. This has led to short term rises in wages. Both major parties are expecting to re-introduce massive levels of immigration.

Net effect

There are signs of growth in wages. But there are a host of headwinds. We are still expecting inflation to moderate.