The one Australian Economic question that matters

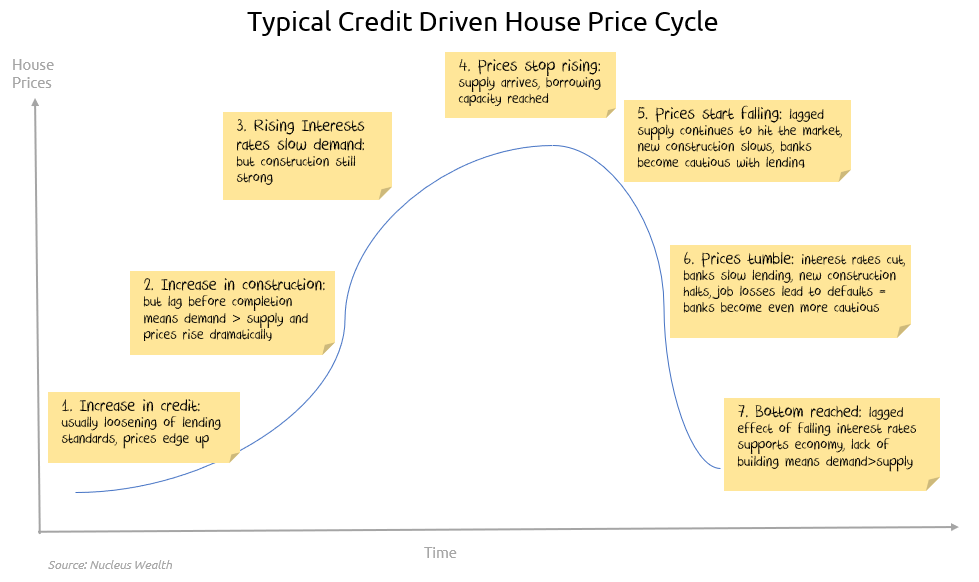

First, I need to set the scene. I wrote recently about how messed up the Australian economic cycle is, noting that housing booms come in several different flavours. Australia had a credit-driven housing boom from 2012 to 2017, and those types of boom/bust cycles usually have the following elements:

This is not the Australian cycle

- In Sydney/Melbourne the construction was primarily apartments, which take a lot longer to build, and so the usual lags on both the upside and the downside are longer. In Perth, rising unemployment meant prices fell despite the credit boom.

- Then the Banking Royal Commission stepped in to restrict lending. Sydney/Melbourne jumped ahead to elements of step 6 without the job losses (yet).

- Now the Morrison Government is trying to spark step 1 of the process by loosening credit again, and the Reserve Bank has cut interest rates.

- Meanwhile, we have the Royal Commission unequivocally condemning bank lending processes, followed by ASIC losing a pivotal court case which suggests lending processes were fine, followed by ASIC appealing the decision.

- To top it off, there hasn't been any deleveraging - Australians still have record housing debt. And construction job losses are coming. And new construction has crashed. And there is still apartment supply coming on. And the global economy is weak.

So it isn't a typical cycle. As I wrote:

Is the Australian government really pinning it's economic growth hopes on trying get the world's second most indebted consumer to borrow even more?

It is a (morbidly?) fascinating economic experiment that the government has launched, seemingly in concert with the regulators.

We know from examples in numerous countries over history that housing booms can occur when the regulators are asleep at the wheel but there aren't many examples we can look at where the government are actively encouraging over-leveraged consumers to borrow more and the regulators to stay out of the way.

There are plenty of cases where we have seen housing cycles spark economic growth. We just saw it from 2012-2017, and ten years earlier we saw the same effect process play out in the US.

Here is my take on the key factors affecting the housing market:

The one question that matters

And with the scene set, that leads us to the question alluded to in the headline:

Can rising house prices drive the rest of the economy on their own without a construction boom?

For the optimists, the answer is a resounding yes. House prices have not only stopped falling but have risen over the last month. Buyer queues are out the door for limited supply which will inevitably mean rising house prices. And Morrison's 95% lending for first home buyers hasn't even begun yet. Investors will follow first home buyers, which will lead prices higher and then upgraders will start buying again. Rising property prices will mean consumers will start spending once more, construction will recommence, and a new Australian economic growth cycle will begin.

It would appear that the Federal Government has this belief.

Pessimists have a different take.

The worst arguments mounted by pessimists tend to have a moral angle: house prices are too high for children to afford, they will have to come down to a level that an ordinary person on a regular salary can afford. If that occurs, then house prices will fall 30-40%. While these arguments are compelling from a social justice perspective, or on a long term basis, the same arguments have been valid for 15 years - timing is important.

The better argument notes that even with a sunny outlook for construction, employment will fall for at least another year as the construction decisions made over the past two years affect the number of people employed.

Rising unemployment in Perth led to a 10% house price fall in the 2012-2017 period while Sydney/Melbourne house prices boomed. What is to stop the same fate for Australia as a whole?

Per capita income has gone nowhere for 7 years, so it is hard to see any rescue coming from that front:

Can rising house prices drive the rest of the economy on their own without a construction boom?

will be found in whether increases in unemployment remain contained. I'm skeptical - but if I'm wrong this is where we will see it.