The St Louis Fed recently did an interesting AI survey that suggested the benefits of AI are large in certain areas but far from uniform.

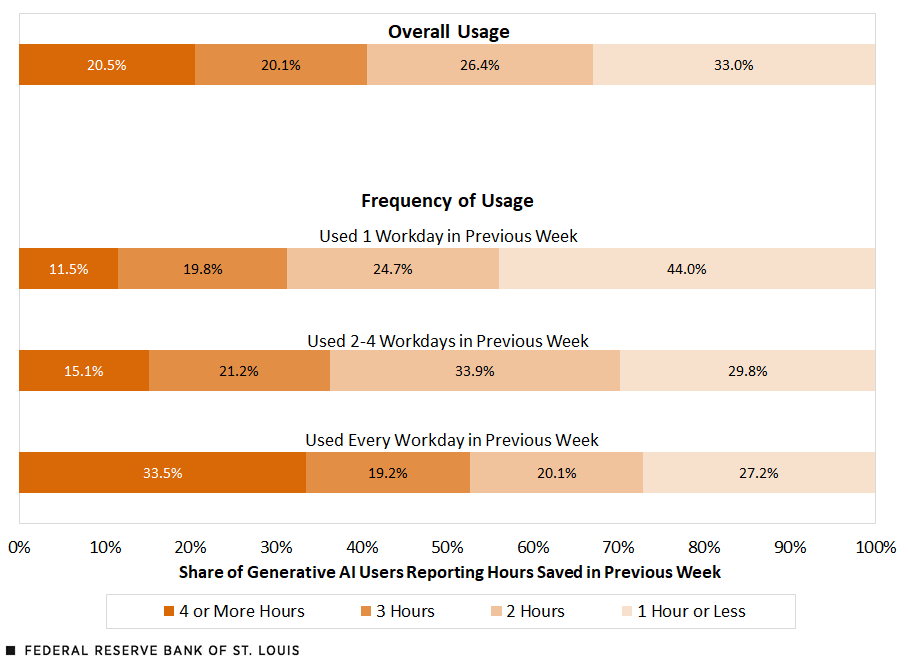

For each generative AI user, we computed the percentage of working hours saved as the ratio of time saved in the previous week to hours worked in that same week. We found an average time savings of 5.4% of work hours in the November 2024 survey. For an individual working 40 hours per week, saving 5.4% of work hours implies a time savings of 2.2 hours per week. When we factor in all workers, including nonusers, workers saved 1.4% of total hours because of generative AI.

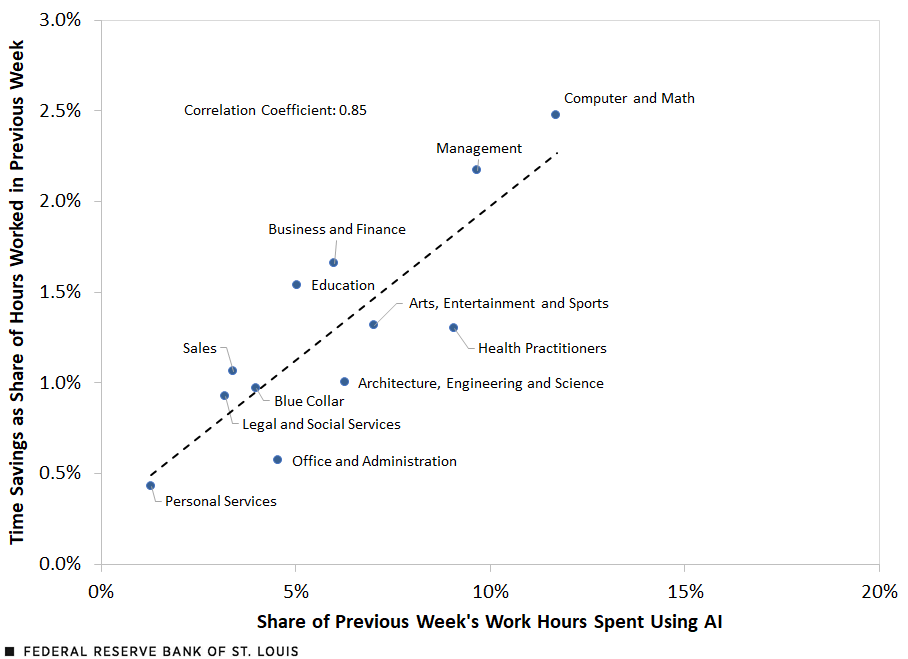

The next figure illustrates how generative AI-driven time savings vary with usage across occupations. Time savings and overall usage are highly correlated. Workers in the computer and mathematics occupation used generative AI in nearly 12% of their work hours, and they reported this saved them 2.5% of work time. By contrast, workers in personal service occupations used this technology in only 1.3% of their work hours, and it saved them only 0.4% of work time. The slope of the dashed regression line is 0.17, indicating that a 10 percentage point increase in the share of time spent using generative AI is associated with a 1.7 percentage point increase in the time saved as a share of hours worked.

This does not look overly promising for the Australian economy, which is mostly mired in the bottom left corner of the chart.

Education and finance look more encouraging. My own use of AI suggests that education, in particular, is an area where AI might make a much bigger impact than this. ChatGPT is a lot smarter than any professor I have ever met.

Yet, overall, this disappointing outside if computing and then there is the reverse effect to consider. AFR.

In the right hands, artificial intelligence can clearly be a force for great good. It’s just that I keep coming across people like Sarah Harrop, who know how dire it can be in the wrong hands.

Harrop is an employment partner at the Addleshaw Goddard law firm in London, which means she deals with claims of unfair dismissal, discrimination and other forms of mistreatment.

Since the arrival of ChatGPT, she says there has been a distinct rise in the number of vastly more detailed, lengthy and outwardly credible correspondence to HR departments and employment tribunals.

The documents often contain references to legal precedents and other references to the law that don’t always turn out to be accurate but take hours to sort through.

“We have seen examples where there are dozens and dozens of pieces of correspondence sent to the employment tribunal,” she told me.

The length of the documents and the speed at which they are generated suggests they are almost certainly produced by robots rather than humans, she said, adding this causes “significant pressure” for employers and tribunals.

I can well imagine what a tedious and costly burden this can be for employers, and I am sure they are not alone.

Indeed. I recently had an experience with a Telstra bill that was downright alarming in the above sense.

I spent more than hour being passed from AI chatbot to AI chatbot trying to sort an issue only to discover I had been scammed along the way and then had to spend another hour unwinding the scam.

All claimed to be human beings, none were, and I ended up finding the grotesquely inefficient act of calling Telstra and being passed around on the phone more efficient than the AI runaround.

There are huge gains to be made in some sectors, I am sure. But Australia’s lopsided immigration/consumer economy does not look like one of them.

July 3, 2025