Investing in a world of vested interests

Vested interests are everywhere, chipping away at the moral fibre of politicians, tilting taxes in their favour and diverting resources. In a more diversified economy, the vested interests compete with each other for government favours - a waste of money I'm sure, but there is some benefit in that no one type of vested interest dominates.

However, some countries - Australia and China in particular, are focussed on a particular type of economic growth which means the vested interests in that sector become more and more powerful and concentrated. When the economic growth model is exhausted, these vested interests resist any change - using their political power to stymie a shift to a new growth model. Usually, this means that a crisis is needed before any change can occur.

The Pettis Thesis

This recent Michael Pettis video discusses the growth of China in terms of economic models:

The key point Pettis makes is that China is running a Gerschenkron economic growth model, which has been run by many countries in the last 50 years including Russia, Japan, South Korea and a number of Latin American countries. The model works like this:

- By repressing consumption China increased their savings rate

- This savings was diverted into investment

- Most of the investment was centrally managed infrastructure spending (as the private sector is not good at that kind of investment)

- China also kept interest rates low (below inflation for many years) which penalized savers and benefitted companies and governments

- At first, the investment earned great returns (as China was in dire need of investment) and was hugely successful at increasing wealth for everyone

- As time went on, the investment projects generated lower and lower returns

- Finally, the return on investment fell below the return on debt and the debt burden began to grow

- At this point, you would think that a new growth model would need to be created – but in every other country that has followed this growth model they have stuck to the old growth model and kept increasing the debt until some form of crisis forced a change.

It is not a straight line

The themes are similar to ones we have espoused on numerous occasions, and while these themes were considered outlandish 7 or 8 years ago, most economists now recognize at least some of the unsustainability of the Chinese growth model.

But the decline in growth won’t happen in a straight line, the issue is timing and takes years to play out.

For an investor, recognizing this in 2011 and 2015 was very useful for getting out of the way of falling resources and a falling Australian dollar.

Then, in 2016/2017, increased Chinese capital spending (accompanied by rapidly increasing debt) reversed the process.

From here the risks appear to be more to the downside than the upside.

But don’t forget vested interests.

Vested interests made a fortune from the rise of China, and they don’t want the party to stop. More bridges, more apartments, more airports and more train lines.

China’s growth model was unsustainable in 2010 and is less sustainable now. But there is still scope for the model to be pursued for a considerable period of time - with less and less of an effect every year.

My expectation is that we are in the grind lower phase, where minor measures will be attempted to improve growth (with little effect) until growth slows enough or vested interest bleating becomes loud enough for another round of stimulus.

China probably avoids a crisis, but a policy error at the wrong point could result in a crisis.

The second derivative of growth

If you were a small, open economy with significant mineral resources, should you choose to restructure your economy by allowing the currency to rise so far that manufacturing was decimated and your economy became dependent on mining capital expenditure which was in turn dependent on an unsustainable Chinese economic growth model?

But it is too late, that horse has bolted for Australia.

The question now is how to restructure the economy in the aftermath.

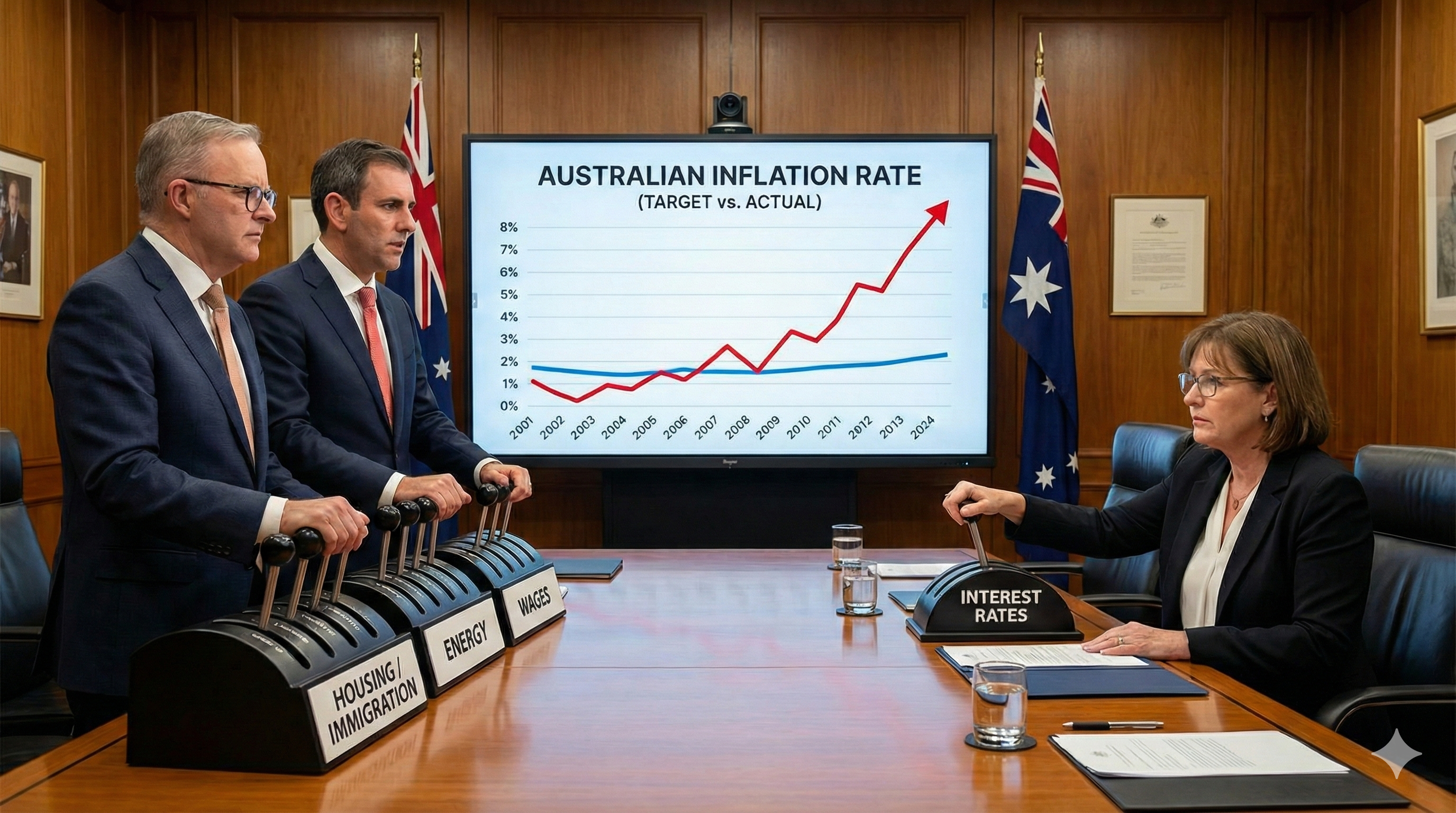

It appears that the first plan was to lower interest rates, and then look the other way on lending standards, international investment and money laundering as property boomed. Job done!

Now that property is coming off its highs, I’m not sure what came next in government and regulators minds – I suspect most didn’t think that far ahead. For the moment, the plan appears to be to try to keep the housing boom going as long as possible.

For my part, the next “boom” is probably going to be business investment. BUT, that is going to need a much lower Australian dollar, and probably a recession first.

My key point is that the more vested interests resist change, the more the burden is shifted onto the rest of Australia and the lower the Australian dollar will need to fall and the deeper the economic downturn will need to be in order to enact change.

So, who are the Australian vested interests?

Australian vested interests

Pettis talks about the problems of countries that have grown using a Gerschenkron economic growth model being unable to change due to the power of vested interests. But that problem is not just constrained to that particular economic model – it infects all countries who are primarily reliant on only a few avenues of growth.

The Australian vested interests who have done the best out of the last 20 years of growth are:

1. Resource Company vested interests

Mining: The vested interests who benefitted from the mining boom managed to kill the mining tax, and still to this day are hell-bent on trying to prop up the coal industry through some mix of subsidies, reduced taxes, subsidized infrastructure to the Adani mine or penalizing green energy. Mining vested interests had a key role in deposing a Prime Minister, and so politicians are unlikely to take on the mining sector anytime soon.

Gas: The biggest wins for this sector from vested interests was the PRRT (a complicated scheme for paying royalties which basically results in most new wells not paying royalties) and managing to avoid gas reservation on the east coast. In combination, the sector pays minimal taxes and gets to charge monopoly-style prices across Eastern Australia. As both major political parties are complicit, there is little in the way of political fallout. In a macabre way, you need to respect what the vested interests in the gas sector have achieved. For the gas sector, it is hard to know what else they could possibly want from the Australian government – what can you give the vested interests that already have everything?

2. Real Estate Vested Interests

Direct: The real estate sector has a considerable hold already over Australian policy. Start with the strategy of running a "big Australia" policy and record immigration. Then add first home buyer grants, special taxation treatment for negative gearing, no capital gains tax on own property, half capital gains on anything held longer than a year, no land taxes, allowing gearing in a superannuation fund to buy property, no compliance with anti-money laundering requirements, and I’m probably missed a bunch of others.

Indirect: Banks, furniture retail, basically anyone benefitting from a big Australia policy.

Investment Outlook

All of the vested interests are busy working on making sure that the models that made them rich over the last 20 years don’t change. But economic conditions are changing, and these the growth that drove each of these models is becoming exhausted. The question is will Australia need some sort of crisis before the old economic models are abandoned? If history is any guide, then yes.

The gas sector is going to be a drag on growth for the rest of the Australian economy through higher gas and electricity prices. Both miners and gas companies are “under represented” in the tax tables.

But we are probably at the peak for both mining and gas in terms of skewing the playing field in their favour.

If the property market really starts to gather some losses, I’m sure there are more policy initiatives that can be instigated. Larger first home buyer grants, stamp duty cuts, allowing people to dip into superannuation, more immigration, more tax rorts - there is lots more that can be done. The current Australian Federal Treasurer's job used to be National Manager, Policy and Research Property Council of Australia - i.e. his job was literally to come up new policies for property companies to lobby the government to skew the playing field in their favour.

So, my expectation is that as the end of the property cycle becomes more apparent, the playing field will actually become more skewed to property vested interests.

Where does that leave us?

Vested interests have skewed the playing field in their favour, and so the more the burden is shifted onto the rest of Australia. The Australian dollar will need to fall further and the deeper the economic downturn will need to be in order to enact change.

From an investment perspective, I'm keeping our investors out of Australian equities, through a mix of international stocks (valuation dependent), government bonds and cash.