About those Australian dividend yields...

At a headline level, Australian dividend yields look good. They paid out 4.5% last year, and are forecast to be 4.8% for next year. Well above global developed markets of a little more than 2%. But, as I showed with valuations last week, the story is more complicated under the surface.

High Australian dividends are partly a function of our tax system

Franking credits are of no use to companies. So, they want to shovel them out to investors as quickly as possible.

What you often see in Australia is companies raising capital from shareholders while at the same time paying similar amounts out as a dividend. To the same shareholders. From an efficiency perspective, this seems crazy. Why pay all the investment banking and administrative fees when you could just keep the cash and not pay a dividend?

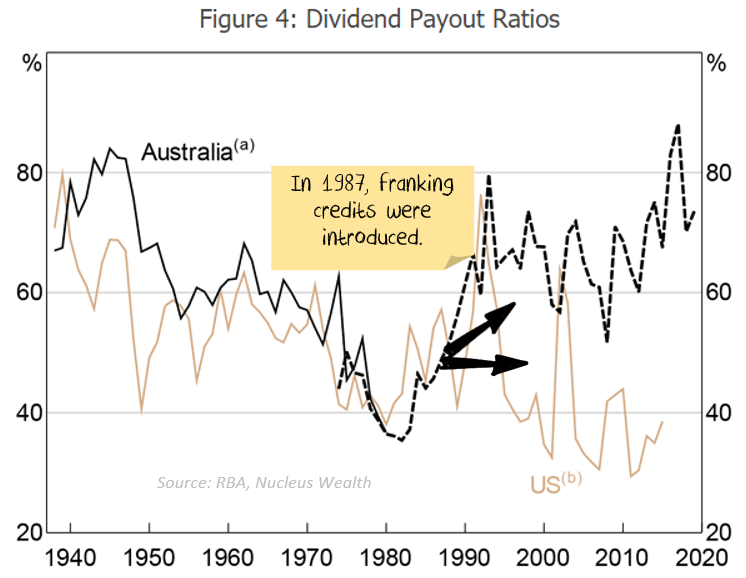

The main reason is tax. By paying a dividend, the Australian company releases the franking credits to investors. You can see that the Australian dividend payout ratios diverged from the US after the introduction of franking credits:

The cost of higher dividends is lower share prices

Internationally, it is more tax efficient to: (a) pay out a smaller dividend (b) use the left over money to buy back shares. This reduces the number of shares and makes each share worth a little more. So, the return is the same. It is a question of whether you want the return paid out as cash or accrued as a higher share price.

If you add in the effect of buybacks, you can see that Australian companies are much more similar to international ones:

Australian dividends tend to be more volatile

International stocks tend to have more stable dividends. If you look at the S&P as an example, the dividends climb quite steadily from year to year:

In contrast, the level of buybacks can vary wildly:

You can think of Australian dividends effectively as a combination of dividends + buybacks because of the Australian tax system. In that case, it makes more sense why the Australian dividends are more volatile than those offshore.

The highest Australian dividend yields are in the riskiest sectors

While forward dividends are expected to rise this year, analysts have the yields falling the year after. This reflects high commodity prices that are not expected to last.

The falling dividend provides a clue as to the underlying problem:

Yes, dividend yields are high, but the high dividends come in sectors that might have the most at risk.

Materials and energy are not sectors that pride themselves on stable dividends. On the contrary, these dividends are the most volatile of any sector.

Next on the list is financials, primarily the banks. You don't need a particularly long memory to note most banks cut dividends by more than 50% in 2020. So, are you worried about rising interest rates spurring a sustained housing decline, or worse, a housing crash? Then you may not want all of your dividend eggs in that basket.

The net effect: you get a high dividend yield, but probably not a stable one.

High Australian dividend yields are partly a function of historical happenstance

Over 50% of the ASX 50 by size is resources and banks. In contrast, those sectors are only around 10% of global stock markets.

If you simply bought ASX stocks (no global ones), but used the same sector weights as international stockmarkets, you would almost halve your dividend yield.

i.e. an overwhelming reason for the higher yield on the ASX is because you will put more than half of your portfolio into resources and banks.

Put another way, if BHP decided to redomicile to London, the ASX dividend yield would fall by around 0.5%. To keep a high yield, would you then put 10-15% more of your investments into other resource stocks?

Investors in other countries, particularly income investors, would shudder to have such an extreme exposure to two sectors. But in Australia, because that this the structure of our market, that kind of allocation is fine.

Net effect

Higher dividends aren't derived from some magical Australian advantage. Higher Australian dividends are a function of:

- Our tax system, which results in higher dividends and lower share price appreciation.

- A concentrated exposure to sectors with riskier dividends.

You may be fine with both. But don’t pretend that higher Australian dividend yields come with no strings attached.