History is written by the victors

My day job is a mix of quantitative and fundamental investment analysis. What that essentially means is that I spend my time looking for situations where the numbers don't match the narrative - and I can't help but notice that in the Australian Federal election result the narrative and the numbers are miles apart.

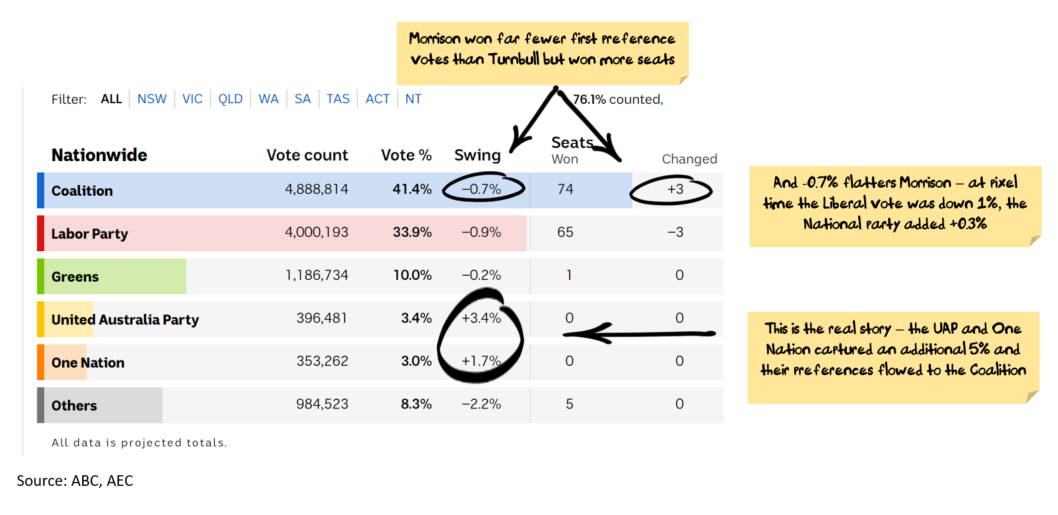

Scott Morrison and the Coalition are chalking this victory up to a splendid campaign and a reconnection with middle Australia. The numbers suggest:

- voters abandoned both the Liberal party (-1.0%) and the Labor party (-0.9%) in droves, but due to preferencing (particularly by Clive Palmer) those votes ended up back with the Liberals.

- the Liberals have done much better than Newspolls suggest, which is being treated as a strategic masterstroke by Morrison rather than an inditement of polling results

Remarkable question is whether Newspolls have been wrong for years, my guess is that they probably were. And so that probably meant two things (a) much of the Coalition instability was due to measurement error rather than a fundamental disconnect with voters (b) Labor falsely assumed that Bill Shorten was doing a good job despite his poor personal polling.

History is written by the victors

The history that the Coalition seems to be trying to write is that Morrison is respected and admired by the population which led to a +0.7% two-party preferred swing to the Coalition and their re-election. The first preference numbers tell a different story:

The data suggests:

- Morrison won far fewer votes first preference votes than Turnbull did last election

- The National party did much better than last election

- Shorten helped by winning far fewer votes than he did last election

- Morrison was effectively bailed out by Clive Palmer and One Nation preferences. The state that the Coalition did the best in (Queensland) was also where Palmer and One Nation votes were strongest

- The distribution also mattered - a lot of the votes lost by the Liberals turned safe seats into less safe seats. Ironically, the Liberals seem to have lost a lot of "the base" that Abbott/Dutton et al are so keen to reconnect with.

Morrison deserves credit for bringing stability to the imploding Liberals. However, the real heroes for the Coalition look to be:

- Pollsters who convinced the Labor party they were on the right track

- Clive Palmer and the United Australia Party preferences

- Michael McCormack (for those of you who don't recognise the name, he is the current leader of the Nationals and deputy prime minister)

Issues for Pollsters

In the aftermath of the Trump election, there was a lot of talk of undercounting of conservative views and pollster errors. There are already similar conclusions being drawn for the Australian election. This is not the same as the Australian election. Our mistakes are different.

To start with, the overall US voting numbers weren't that far off the opinion polls (Hillary won the popular vote convincingly), but the key pollster error was not enough attention paid to the distribution of voters in key states which led to a Trump win. Relatively slight underestimating of the Republican vote in those states was enough to confuse the pollsters into thinking that Trump would certainly lose.

There is a lot of soul searching among pollsters following the election over what went wrong, and it is clear that there are significant problems with both election intention polling and exit polls.

Mark the Ballot had the interesting observation prior to the election about the above table:

And what a remarkable set of numbers they are: The 16 polls taken since April 11, when the election was called, have all been in the range 51-52 for Labor and 48-49 for the Coalition.

If we assume the sample size for every one of these polls was 2000 electors, and if we assume that the population voting intention was 48.5/51.5 for the entire period, then the chance of every poll being in this range is about 1 in 1661.

Now maybe we happen to live in the timeline where the 1 in 1661 chance happened to occur.

But there would also seem to be a relatively strong possibility that:

- polls are having with problems getting representative samples

- pollsters are resorting to statistical adjustments to adjust for non-representative samples

- these statistical adjustments are leading to clustering - no one wants to be an outlier and so statisticians make adjustments until they aren't outliers

I also suspect that Clive Palmer created issues for the polls as his party did not exist at the last election. If Clive opts not to spend $60 million next time, then there is likely to be the opposite problem for polls.

Regardless, it would seem that polls should be treated with much more scepticism going forward.

Investment issues

Politicians have far less effect than many think on the performance of stock markets and economies. This is partly because there is less difference between the policies of the different political parties than the politicians want you to believe, and partly because they have only limited effect on economic outcomes - central bank decisions are more important in most countries.

This is more true for Australia than most, as a small open economy Australia is highly dependent on global commodity prices which political leaders have even less effect on.

So, don't overplay the effect of elections in general. Having said that, I do expect a positive short-term effect and a negative medium-term effect from the re-election of the Coalition.

Short-term effect

The Labor party had policies that would have been negative for house prices which would have increased the possibility of house price declines sharpening. That crisis has not been completely averted, but the chance of a negative tail risk event has decreased. Our expectation is that Morrison will also be more aggressive in trying to bail out the housing sector as house prices continue to weaken.

Medium-term effect

One of the structural problems with many global economies is a lack of demand and what is being termed "secular stagnation". Our assessment is that much of the secular stagnation is due to inequality and stagnant wage growth. Labor had a number of policies to address those risks in Australia, the Coalition does not. We expect low wage growth and secular stagnation to continue to be a feature of the Australian economy.