Is bad news no longer good news?

The stock market tends to be driven by narrative. For much of last year, the narrative was that bad news was good news. Bad economic news meant bond yields fell and inflation expectations cratered. However, it also meant more central bank intervention. Growth stocks boomed. In a time of no growth, any stock that did exhibit six months of growth would "therefore" grow forever. Even better if the stock didn't make any profit! A lower bond yield meant investors could pay more for those stocks. In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man became king.

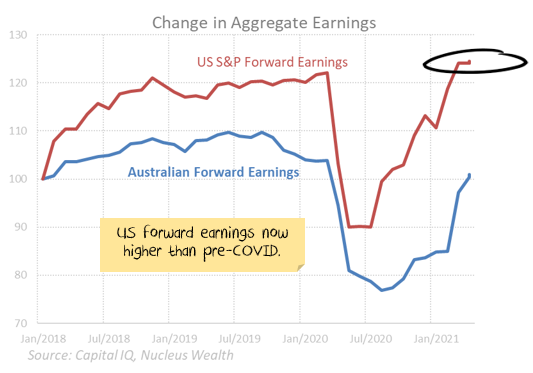

The narrative changed sharply in November. Vaccine success and a new, big-spending government in the US revived hope for growth and inflation. The new narrative became good news was good news. Good economic news meant higher profits. Value stocks became the new leaders, and growth stocks sank. Banks, cyclicals, commodities all shot higher on the expectation of rising economic growth.

There is one more narrative circulating through financial markets you should be aware of. We are calling this one good news is bad news. It is basically the reverse of the first narrative. It assumes that the rising bond yields and inflation will burst the stock market bubble.

Which narrative will reign supreme this year?

- Bad news is good news. Ongoing deflation (after a brief inflation spike) and further central bank intervention will see asset prices outperform the economy.

- Good news is bad news. The stock market boom will go bust as inflation and bond yields rise.

- Good news is good news. Expensive stocks can weather higher rates because the profits boom is real and central bank/government support will not be withdrawn prematurely.

The least likely, in my view, is the "good news is bad news" option. Not only do I think that the inflationary pressures will be temporary, but I also believe in the central bank "put". i.e. central banks do not want bond yields to rise to the point where they damage economic growth. The Australian and European central banks have expressly commented on this. The US Fed has avoided explicitly commenting, and so maybe markets will test their resolve. This could lead to short term pull-backs, but these are more likely to be buying opportunities.

Our position is that profits growth will put a sizeable dent in the overvaluation as inflation spikes. But that will fall back, driving violent rotations under the equity hood but no major breakdown in the engine itself.

So, the focus right now is on the "good news is good news" argument. Deflation and disinflation are likely to take over in the coming months, but that is a theme for later.

There are other risks.

Investment markets are distorted by central bank buying and government stimulus. The number one risk for the next few years is a policy mistake. But nothing seems imminent on this front.

There are ongoing virus mutations and problems with some vaccines. At the moment, these issues look solvable.

Given elevated debt levels, a debt crisis is possible. It is unlikely to be in corporate debt markets where central banks have already expressed a willingness to wade in to bring borrowing costs down.

Hedge funds are a more likely culprit. We've seen Melvin Capital and others lose vast amounts on a short squeeze in the past three months. Then Archegos blew up, over overleveraged on long positions that moved the wrong way. With so much debt, expensive markets and such low interest rates, there is an ever-present danger. The next one may be large enough to threaten financial stability. On the other hand, moral hazard is in short supply. If the blow-up is big enough, central banks and governments would probably step in.

Governments globally have been willing to suspend rules around bankruptcy and generally allow consumers to not pay loans. As these rules are progressively lifted, there may be problems. But globally, rising house and stock market prices have alleviated the most obvious issues.

The common thread is that moral hazard is no longer an issue. Need to suspend the rules of capitalism and prevent bankruptcies? Go for it. Do you want central banks to print money to reduce the cost of corporate debt? Not a problem. How about central banks lending money to commercial banks to keep them profitable? Just hide your program in plain sight behind an acronym like TLTRO or TFF, and no one will bother to ask questions. So much money has been spent or printed that few are bothered to be outraged anymore.

The one place where I'm pretty sure there would be backlash would be an emerging markets debt crisis. US growth is looking like it could be much stronger than the rest of the world. This could lead to a significant rise in the US dollar. That could create conditions similar to the Asian crisis in the late 1990s. This isn't a base case, but it is one of the only debt areas that central banks and governments would face resistance to rule changing/money printing solutions.

Summary

The categorisation of the narrative options into good/bad is clever semantics. And my favoured narrative, good news is good news, is the only non-contradictory semantic.

However, the categorisation probably over-trivialises the other narratives.

They are genuine possibilities. I am closely watching for signs that growth is tapering and deflationary forces are again reigning supreme. While the result in that narrative is still "good news" for stocks, the affected stocks are very different.

This is not a "set and forget" market for asset allocators.