The magic of manipulated valuations: WeWork vs your Superannuation

WeWork put its Initial Public Offering on ice this week as the company realised it would not be valued at the $47 billion that WeWork wanted. Indications are that WeWork would struggle to raise money with a $15 billion valuation.

The process WeWork took to get a $47 billion valuation is instructive for anyone with money invested in a Superannuation fund with significant unlisted assets.

WeWork is an unlisted company. Which means WeWork is not traded on a stock market, instead it is owned by a small number of investors. It also means WeWork traded infrequently - in this case, whenever WeWork needed more money.

The problem is that valuations were done by WeWork or a handful of investors based on what they thought they could eventually sell WeWork for. One major investor in WeWork, Softbank, has booked significant favourable investment performance based on the increase in theoretical value that Softbank imagined had occurred. Now Softbank will need to reverse those gains.

For investors trading in or out of Softbank in the meantime, it is a problem as the billions of dollars of gains simply weren't real.

A similar situation faces much of the Superannuation sector. Now I'm not suggesting all unlisted assets will need to be written down by two thirds like WeWork. But I am saying we just don't know whether the reported performance is accurate or not.

As I wrote earlier this year:

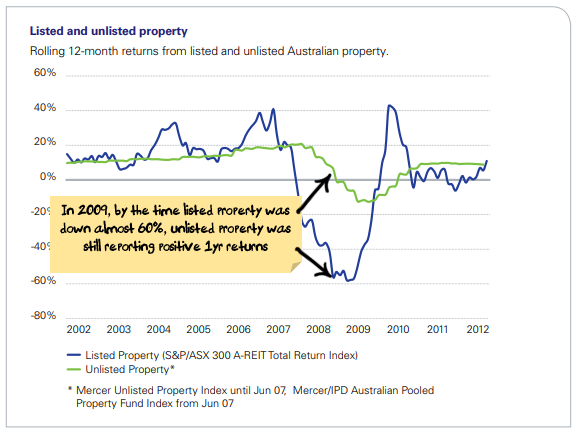

This is the issue when comparing funds that invest in listed assets vs ones that invest in unlisted assets – you have no way of knowing the actual value of the unlisted assets. A great example is unlisted property funds during the financial crisis. Unlisted property funds invest in effectively the same assets as listed property funds, the underlying properties are worth the same, the performance differs because of how it is reported:

Do you really think that while listed property prices fell almost 60% over a year, unlisted property prices had increased slightly over the same year? They both own the same buildings, it is just that unlisted assets don’t get valued regularly and so the values being reported were the values from prior years and didn’t reflect the actual market value.

By this stage, unlisted property funds weren’t trading anyway and so you couldn’t sell your unlisted asset at the inflated made-up prices – who would want to buy unlisted property assets at last year’s prices when you could get listed property assets at almost 60% off?

So, this is the trillion dollar question. Is an unlisted property trust less risky than listed property? There are a lot of people who say yes as the reported prices are less volatile – but my emphasis on the word “reported”.

For me, if it is the choice between owning an asset:

- in a listed vehicle where I can see what is happening, how much it is worth and buy/sell at any time, or

- in an unlisted vehicle where I don’t know what is happening, the asset can only be sold at infrequent intervals and the valuation is a mix of prices from prior years and management estimates

then I will take option 1 every time. Just because I can’t see the price move doesn’t mean that it hasn’t.

On average, Industry Funds have about a quarter of their assets invested in unlisted assets. For some, the figure is much higher. Which means the level of uncertainty is higher.

With full disclosure, some of my rant is probably sour grapes! We run superannuation funds at Nucleus, and it is all in liquid listed instruments - investors can see each and every underlying holding. We don't have anywhere to hide. Some months I wish we had 25% of assets in unlisted funds that could be strategically revalued...