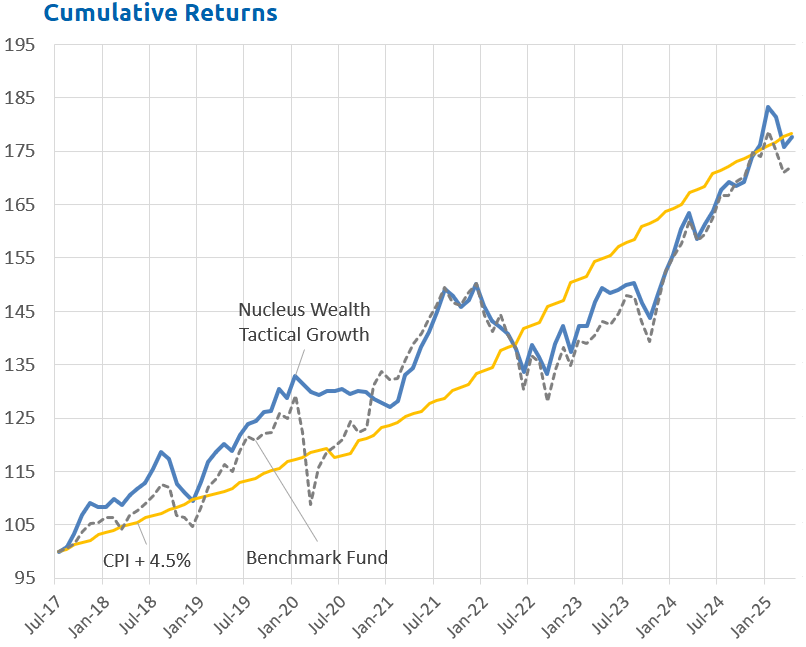

March 2022 Performance

The Australian stock market boom continued into March, although it is showing signs now of petering out. Commodities are the main story, and tremendously volatile. Over the last 12 months, iron ore more than halved, then added 50% and is now oscillating around the $150 mark. Oil and gas have been similarly volatile.

From here, there are some serious questions to be asked of commodities and therefore the exposure to Australian stocks.

The glass-half-full story is that the Ukraine invasion and Russian sanctions will benefit Australia. Australian exports of iron ore, wheat and gas will replace Ukraine and Russian exports, commodity prices will remain high and the ASX will continue to boom.

The glass-half-empty story is that Russian iron ore, oil and wheat will go to India and China rather than Europe, creating short term issues, but merely a reshuffling of supply in the medium term. Spiking gas prices are a short term positive, but have accelerated the move to renewables - a medium and long term negative.

One of the hallmarks of our growth fund to date has been our willingness to reduce risk when we believe the risk/return rewards are not appropriate. Now is one of those times. We are holding over 30% cash and bonds.

Our concern is that central banks are suggesting that they will solve inflation problems, which are largely a result of supply chain issues, by restricting demand. Given the problems that the world has had since the financial crisis, in our view that is not an attractive setup for markets.

We expect international equities to provide some protection from a growth slowdown. While the Aussie dollar is likely to rise if the energy crisis worsens, it is more likely to fall over the medium term. This will hedge the downside under the worst scenarios, whilst still providing some upside in the better ones.

Six warning signs of a global recession

The global economy is in a delicate state. Nearly every major economy is facing some sort of headwind. There are several signs that a global recession may be on the horizon. In this post, we'll look at six of those signs. So far, all of these indicators have been pointing towards a slowdown in economic growth...

Keep in mind that a global recession is typically considered to be growth below 2%.

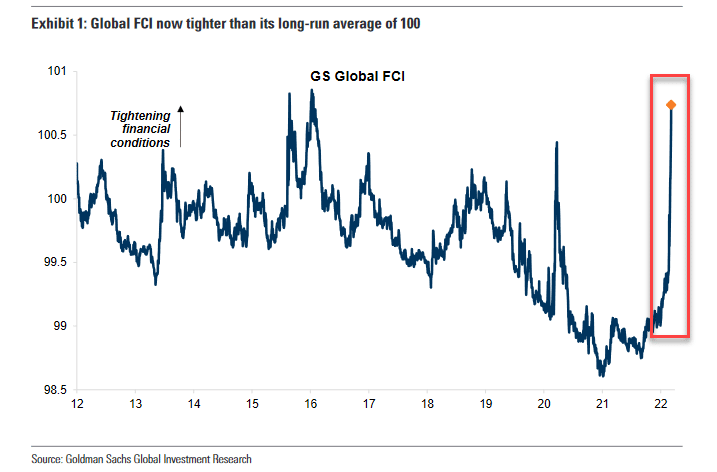

Factor 1. Fiscal and Monetary Tightening

The pandemic inspired a wave of government spending and central bank largesse. Governments issued debt hand over fist to locked-down workers. At the same time, central banks bought the debt to keep interest rates low and spur activity.

But this has come to an end.

Governments around the world have pulled back on spending. Particularly in the US. Remember that growth relies on more being spent this year than last.

At the same time, we are seeing central banks raise rates worldwide. Perhaps more importantly, the US central bank has changed its tune and is now talking about a long series of rate hikes.

Governments will still be running large deficits, but if they spend less in 2022 than 2021, it will be a drag on economic growth. Central banks will still be accommodative. But if central banks are less accommodative than 2021, it will be a drag on asset prices and economic growth.

Factor 2. Surging energy prices

Gas and coal prices have been elevated since late 2021. First due to jockeying around the Nordstream2 pipeline, now due to supply issues following the Ukraine invasion. Gas prices in Europe are still ten times higher than typical levels.

This acts as an additional tax on consumers, reducing demand. In Europe, it has also meant further supply chain disruptions as some companies cease operations, unable to compete at current prices.

Typically, higher energy prices might spur an oil & gas capital expenditure boom which can help to replace some of the lost demand. This has happened a little in the US. However, the global effect is muted. The surging prices and the Ukraine invasion have sparked a step-change in the desire for renewable energy.

There will be lots of capital expenditure on renewables. But in the short term, the supply is limited. This means the world is relying on high energy prices to bring about demand destruction. That is a negative for profits, inflation and economic growth.

Factor 3: The end of the supply chain supercycle

Is the supply chain supercycle over? It is certainly starting to look like it has peaked and is on the way down.

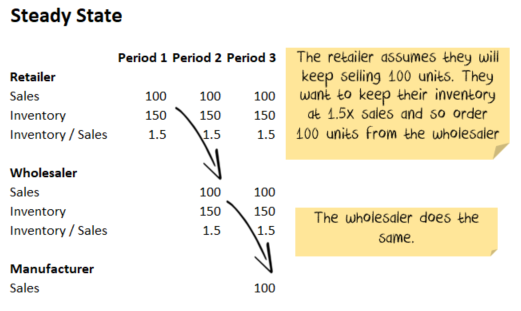

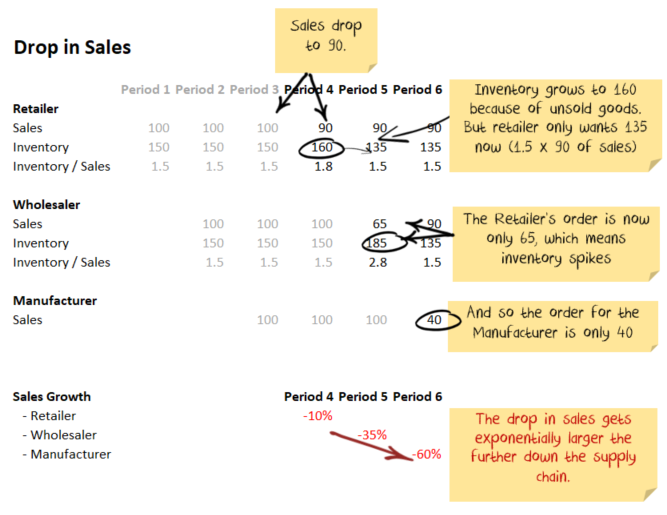

The bullwhip effect describes how businesses need to order far more than what they sell when they increase their inventories. i.e. they need to order for what they will sell in the next period, plus more to increase their inventory. Then, as inventories become full, businesses scale back their orders. The supplier, who by now has often invested in more production, suffers a fall in sales far greater than the retail. See the example below:

There is a very good case that the bullwhip is coming. Quite possibly soon. And it looks like a big one:

- Consumers consumed more goods than services during the pandemic.

- Companies over-ordered to increase inventories after being caught short of goods.

- Supply chain delays meant companies needed to further over-order to account for delayed shipments.

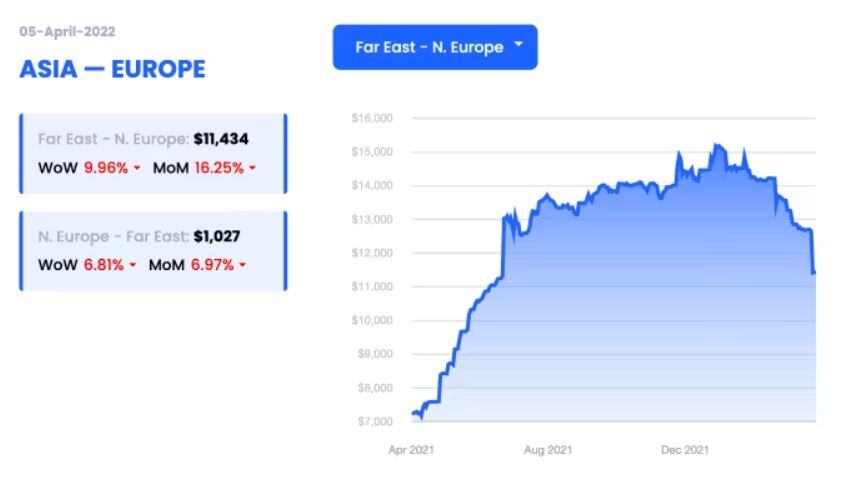

All of these are showing signs of going into reverse. In some markets, transport prices are tumbling:

But, price falls are not evenly spread. So the signs are ambiguous.

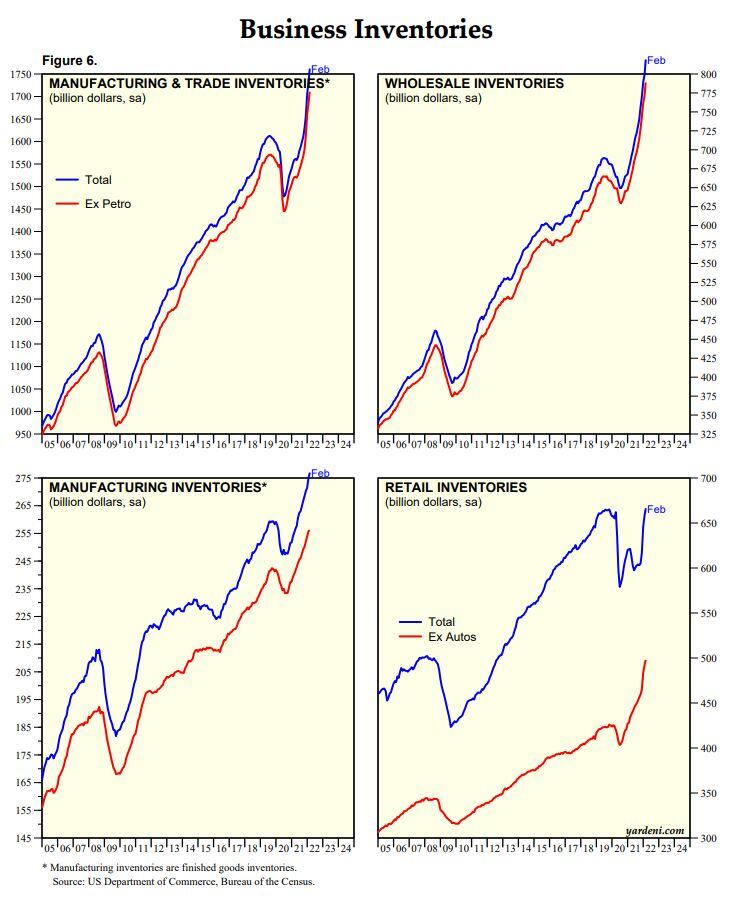

Excluding cars, retail inventories are at record highs. So they would seem ripe for a reversal at some point:

Could it all unravel suddenly? Absolutely. Could it last for months longer? Sure. Further disruptions from the Ukraine invasion or sanctions, China lockdowns or a hundred other left-field events could delay the reckoning.

Watch this space.

Factor 4: The property bust in China

There is an ongoing, slow-motion property bust happening in China. After years of over-building and increasing debt, authorities began a "three red lines" policy to rein in property developer excesses.

This is the fourth instalment of Chinese attempts to rid itself of its troublesome property development sector. The first began in 2011. It was ramped up again in 2015 and 2019. The failing growth that followed spooked policymakers into more stimulus each time.

China keeps returning to this program for one reason. Its property market excesses are the key threat to its economic development path. Property is both the source of its enduring catch-up growth and its doom if allowed to run too far. No other Chinese sector misallocates capital and kills productivity on such a massive scale. If not restructured, it will drag China into the middle-income trap of weak income, stalled growth and declining efficiency.

In 2020, China announced lending conditions for property developers called three red lines. These conditions are now being enforced. It is trying to slow the property lending market, which has grown around 600% over the past decade. In addition, there have been dozens of other minor changes to slow credit to the property sector.

Evergrande but one of many

Evergrande is significant partly because of how big it is. But, more importantly, whatever solution is applied to Evergrande will need to be used on hundreds of other property developers.

The total value of listed companies globally in the Real Estate Developers or Homebuilding industry is a little under USD1 trillion. More than half of those companies are listed in China or Hong Kong. Plus, on average, Chinese and Hong Kong property developers have 3.5 times more debt than developed market companies.

101 minor changes

Every second day there is some sort of announcement out of China about property sector support. Changes to rules on who can buy property, reserve cuts, support for small businesses, tax cuts and more. None of these will stop the fall.

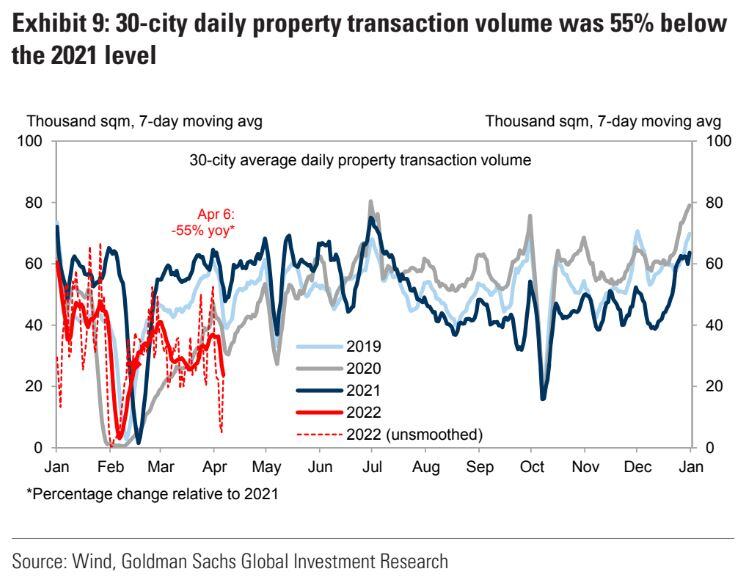

Property sales are down 50%+ on last year. New construction is also tanking.

The only factor that can save the property sector will be a government-sanctioned way to evade the three red lines. This has not been forthcoming.

At some point, China will once increase credit again to the sector in the future. It is not a one-way ticket. However, the long-term trend is down. The downtrend will be punctuated by bursts of credit to strengthen the Chinese economy when it weakens.

The question is whether Chinese authorities will fold quickly this time or want to see more reform before relenting. I expect China to let property slow to at least 2015 levels before folding. Maybe the COVID lockdowns will change that? They haven't yet.

Factor 5: COVID lockdowns in China

OMICRON is affecting around a third of the Chinese economy. Chinese domestic demand is slumping. Factory shutdowns will reduce consumption in developed countries. Can the world handle the decrease in demand on top of all the other problems?

There will likely be stimulus on the other side of the lockdowns. But that is probably months away. And, to date, policies have been targeted mainly at the supply side.

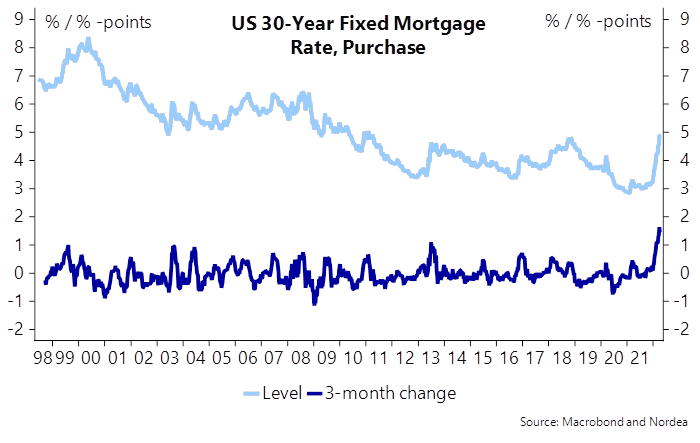

Factor 6: The effect of higher interest rates

Housing affordability has tumbled globally with higher interest rates.

Corporate lending rates have increased substantially.

Both of these are going to slow economic growth.

Have we seen this all before?

- Globalised supply chains reversing into more local production due to geopolitical tensions

- A pandemic disrupting supply chains

- A surge in inflation due to supply issues

- Central banks hiking rates into a supply-side shock

Yes, we have. Following World War I, all of the above factors were in place.

By 1920, inflation in the US was running at 15%. The US central bank hiked rates from 3.5% to 5.6% to curb demand. By 1921 the US was in a depression, with inflation of -10%.

The analogy is not exactly the same. But, trying to use interest rates to solve supply chain problems is at the core. There are more similarities than there are differences.

Investment Outlook

I have some pretty clear ideas about which trends are sustainable and which ones aren't in the long term. However, the short term is far less clear:

- The sanctions on Russia are unlikely to be lifted anytime soon. The short term effect is probably commodity shortages. In the longer term, it seems likely that we will see a re-orientation, Russia will supply more to countries like China and India, less to Europe. For some commodities (oil, wheat) this will be easier. For others (gas) it will be extremely difficult.

- The Omicron variant looks to be resolving in the direction we expected, ripping through economies without too much harm and leaving behind an acceptance that COVID is endemic.

- The geopolitical energy crisis in Europe has turned acute. This will subtract from European growth in the short term, there will be a rush to alternative energy sources in the long term.

- Supply chains have improved a little but are still clogged.

- Demand is challenging to read and distorted by Omicron. Demand held up far better than prior virus waves.

- Governments continue to withdraw (or not replace) stimulus. There will be a fiscal shock in 2022. The question is whether the private economy will be strong enough to withstand it.

- Central banks have made it clear that they will try to solve the Russian induced energy issues and supply chain induced inflation by raising interest rates. The odds of a policy error have increased significantly.

- China still has not bailed out the property sector. China is trying to ensure that houses under construction get built, small businesses have access to credit, infrastructure building continues, and failing developers do not crash the economy. But China is yet to show any signs of turning back to the old days of debt-driven property developer excesses. Unless they change, this will deflate the commodity market.

- Labour markets became more uncertain in January/February as Omicron boomed throughout the world. It will be months before a clear picture emerges.

It is still not the time for intransigence. Events are still moving quickly. But we have positioned the portfolio towards the most likely outcome and are gradually increasing the weights as more data arrives.

Bond yields have risen significantly. If the world heads for recession this is a buying opportunity. The problem in the short term is that the narrative "high inflation, central banks raising rates = sell bonds" is surging still. And the mix of higher volatility, leading to deleveraging of risk parity trades, and momentum means yields could yet go higher. We are dipping our toe in that water but are not quite ready to dive in.

Asset allocation

Stock markets are expensive. Debt levels are extremely high. Government/central bank support continues but is slowing. Earnings growth had been really strong but has come to a halt.

Markets are supported to a great degree by central banks and governments. Policy error is every investor's number one risk.

But, any number of other factors could force this off course and see unexpected inflation. Mutations could disrupt supply chains again. Chinese/developed world tensions might rise further, leading to more tariffs. Or, China might reverse its tightening on property sectors. Biden may get through additional stimulus, driving increases to minimum wages.

We are significantly underweight Australian shares, with the view that the Australian market will be the one most affected by a slowdown in China:

Australian equities have been a good source of investment performance in recent months. We switched out of them and into international equities and cash. We have largely built the defensive side of the portfolio up, changing out of value winners like resources, banks and cyclical industrials.

Performance Detail

Core International Performance

Markets recovered their initial sell-down with our portfolio closely tracking its benchmark. Our property stocks and Meta (Facebook) offset weakness in the Banks as economic slowdown and inflation worries loomed large. The commodity-backed AUD strength meant currency headwinds hindered all regions. During the month we added two tire manufacturers (Bridgestone and Michelin) to the portfolios seeing them as long-term beneficiaries of the move to electric vehicles.

Core Australia Performance

Banks, Energy and Technology were the drivers of the Core Australian portfolio performance with Aristocrat the key detractor. In March we exited Flight Centre which has been removed from the Benchmark and thus our investment universe.

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at Nucleus Wealth.

Follow @DamienKlassen on Twitter or Linked In

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen is an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management, a Corporate Authorised Representative of Nucleus Advice Pty Ltd - AFSL 515796.