There is a certain seductiveness to a bearish investment argument. The chance to appear like a rational actor in a crazy world. The opportunity to be able to say “I told you so” at a future date. The moral superiority of the cautious investor.

The problem is stock markets usually go up. The world belongs to the optimists, regardless of how (frustratingly!) oblivious many optimists are.

I’m no stranger to the bearish argument in recent years. However, I have been careful to temper my caution in the asset allocation of the funds that we run and take a little more risk. For example, during 2019 while stock markets boomed our growth fund finished in front of all but three other growth superannuation funds (according to Chant West):

My point is we are not perma-bears looking for the next crisis to complain about. I’m trying to establish credibility, so you actually listen to my argument. Because, for me, the time for tempering caution is over.

The time for caution is here

Two weeks ago, we spoke in our podcast about the coronavirus and the dangers it presented given where the world is in the economic cycle. Since then, the news has only gotten worse.

There are two elements to the coronavirus:

- Humanitarian. The bigger the shutdowns, the greater the preventative measures, the fewer people will die.

- Economic. The bigger the shutdowns, the greater the preventative measures, the more significant the economic impact will be.

To date, the focus has been on minimising the economic impact. That is no longer the case and now (belatedly?) it is about preventing the spread of the disease. Or, for politicians, at least been seen to be trying. The economy is no longer the issue.

I’m not a virologist, and I’m not pretending to be. I don’t have expert knowledge if the measures will work or not to prevent the virus from spreading. I support measures to save lives at the cost of economic growth.

But I do know that the economic measures to date are significant and the world is not well-positioned for an external economic shock.

Coronavirus is not SARS, and it is not 2003

SARS killed fewer than 800 people and decreased China’s GDP growth by about 2%. The rest of the world was fine. The issue is:

- Coronavirus has already infected far more people than SARS. It may have a lower mortality rate, but it is making up for any shortfall by being far more contagious

- The containment measures already in place are far greater than the measures for SARS. They will have a significantly greater economic impact.

- China is more than 4x larger than it was at the time of SARS. At the time the effect on the world economy was relatively negligible. Now it is much greater.

- Retail, restaurants and tourism are a significantly larger part of the Chinese economy now, and these are more likely to be affected.

- SARS was limited to five main countries. Even if the Coronavirus doesn’t kill anyone in the developed countries, the greater infection rate and the economic effect of containment will be much greater. Already the U.S., New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, Philippines, Iraq, Indonesia, Italy, Australia and other countries have enacted bans that will affect their own tourism industries. More is likely.

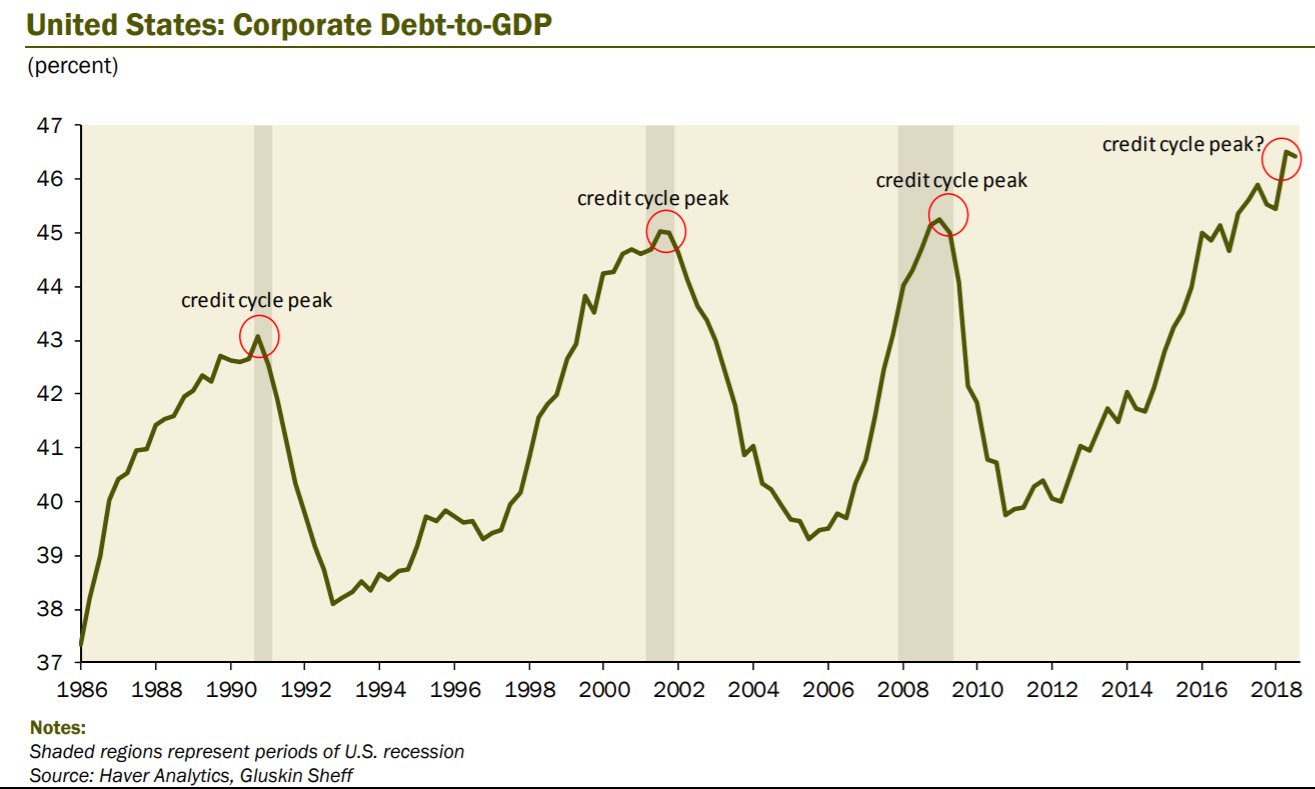

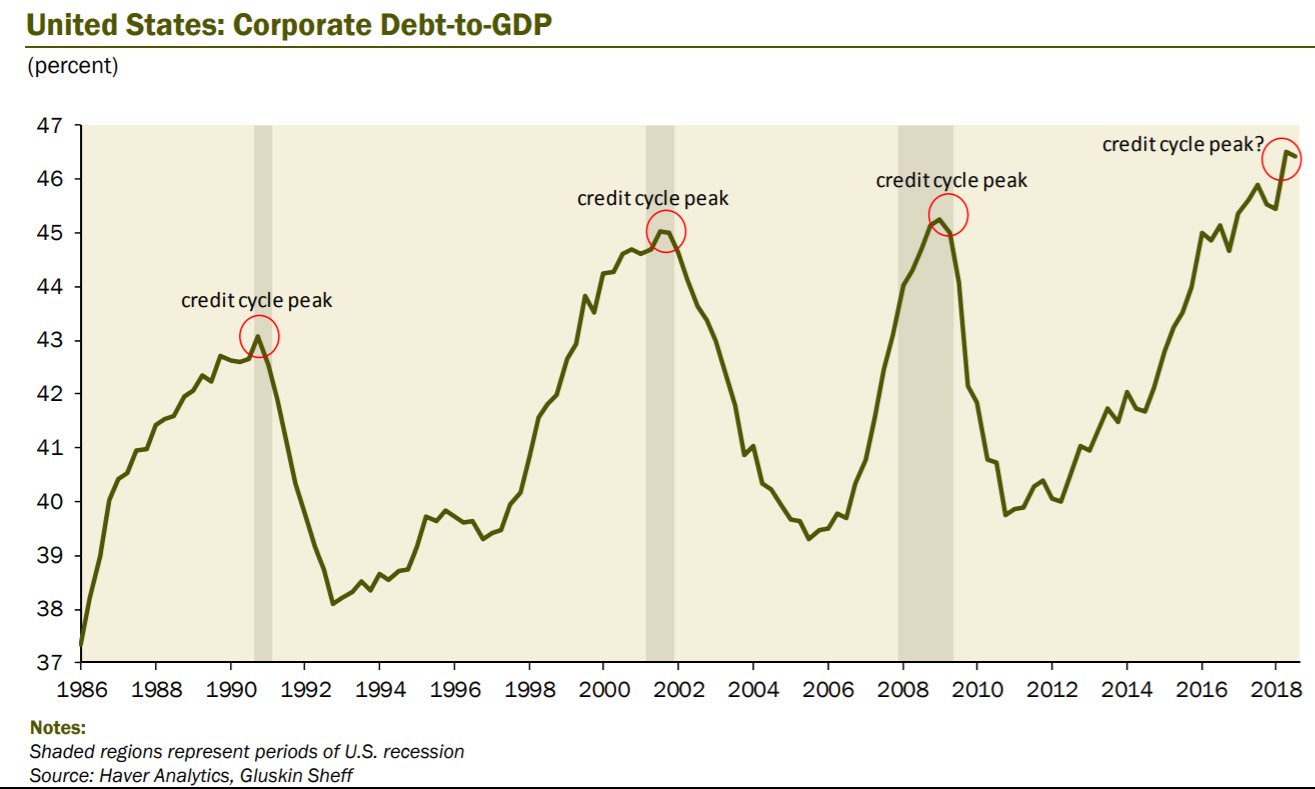

- SARS was basically at the bottom of the global economic cycle. Debts were low. China still had productive investment. The world was about to launch into the mother of all housing booms. Economic circumstances in 2019 are very different.

- Central banks have exhausted conventional measures.

- Corporate debt is at cycle highs.

Where to avoid

Sectors and countries I’m looking to avoid have a number of key elements:

- Exposure to Chinese demand

- Reliant on Chinese and global tourism

- Companies with too much debt

- Countries with consumers carrying with too much debt

- Countries with too much debt not denominated in their local currency

- Cyclical companies, like resources or capital equipment which tend to rise more quickly in booms but fall more rapidly in busts

- Exposure to Chinese students

- Banks exposed to the above

Australia ticks almost every box above. Europe ticks a lot. Canada has a decent spread.

The Counter-argument

The best counter-argument is that there is plenty of liquidity out there. Central banks are pumping the world full of money which is what has driven stock market valuations to current levels.

It is a good argument. It is also an argument that has a binary outcome. Market liquidity is a mind trick. If the market believes in the power of central banks, then stock markets can continue to levitate.

Are you confident markets have (and will keep having) complete faith in central banks? Then you have a reason to continue to buy stocks.

However, if you are concerned (1) negative earnings will result from the containment measures (2) the faith in central banks will disappear once negative earnings appear; then come join me on the dark side.

The Upshot

We, and most fund managers, have made a lot of money for investors during the current cycle.

Earnings growth is negligible. Valuations are more expensive than they have been since the tech wreck.

In my view, now is not the time to be greedy and to try to squeeze the last drop of performance. Instead, we are taking cover to wait for a cheaper, and potentially a much cheaper, opportunity to buy stocks.