September saw volatile, but ultimately strong equity markets push the investment returns for most superannuation funds higher. Our tactical investment funds performed well, and continue to post-investment returns above the returns of most Australian super funds over the last year. This comes despite their defensive stance.

In our portfolios, we are positioned for adverse outcomes, which means we tend to lag the market on strong up months and then make back the returns in weaker months:

Assets are priced for perfection, and we are expecting conditions to be far from perfect:

- corporate earnings are weak globally,

- inflation is almost nonexistent,

- central banks know that they are out of ammunition and are begging governments to borrow,

- largely governments are ignoring these central banks.

The one major exception is the US, although borrowing to give companies and the wealthiest 1% a significant tax cut is not what central bankers would have preferred.

This leaves most of the world relying on US growth to lift exports and demand enough to offset their own government’s failure to act. And with US growth now slowing after the sugar hit of tax cuts last year a range of countries, particularly in Europe, are being exposed as having no actual growth plan. Except for the hope that someone else will do the heavy lifting.

What can go right

This month I’m taking a break from pessimism. I want to play devil’s advocate and explore what could go right with economic growth and investments:

Up is usually the case

In many facets of life, a more cautious approach is the responsible option.

However, the natural tendency is for stock markets to rise more quickly than cash or bonds over the long term. Being too cautious in investing is a recipe for underperformance. Particularly for superannuation.

Yes, there are a lot of things that can go wrong with the stock market and the economy. But there is always something that could go wrong. There is never a period where there are no risks.

So, the hurdle needs to be higher for a negative outlook than for a positive one.

Trump wants to be re-elected

Trump’s best quality is that he is not ideologically wedded to many things.

His worst qualities are the remaining things[Sorry, this optimism thing is hard].This means Trump is capable of changing his mind when the

facts changestock market falls. So if the US economy is genuinely looking at a downturn, then he will do whatever he can to support it.Trump genuinely wants to support the economy fiscally and has no

acknowledgementfear of deficits.In our assessment, this is the right strategy as monetary policy has been exhausted. While tax cuts to the richest are one of the least effective ways to stimulate fiscally, Trump’s willingness to run deficits is relatively unique in the developed world.

Trade Wars

The trade war is negatively affecting both China and the US. While both countries have hardened positions, it is in the best interest of both countries that a deal is reached.

Both leaders are facing domestic issues, and slow economic growth is not helping.

There have been signs Trump is willing to do a deal to solve the problem. His most recent back down shows he is feeling the pressure more than Xi.

Hong Kong

The 70th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party celebrations is over. The celebration had the potential to create a flashpoint, and so the avoidance of that is positive.

Potentially, a US/China trade deal and growing exhaustion will lead the protests to die off.

Brexit

Y2K is an apt analogy. Unrecognised, Y2K had the potential to cause severe issues for computer systems around the world. However, the (relatively) early recognition and hype about the dangers meant Y2K ended up being a non-event.

There is a reasonable argument to be made that Brexit is similar. If Britain left immediately after the referendum, there would have been chaos. But forty long months have passed. Companies and the government have had a lot of time to plan and prepare contingencies.

There is likely to be some short term economic impact. But if the pound falls sharply, there is a reasonable argument that within three or four years, a new British economy will be growing faster than Europe.

There will be fewer financial services jobs in London. I’m unconvinced that is a bad thing for the British economy.

Kick the can

The motto of the political class ever since the crisis seems to be: “Why delay doing something until tomorrow when we might be able to wait until the day after.”

Whatever the problem, if there is an option to delay short term pain and increase the long term pain, current politicians will take that option.

For investment markets, it means more of the same. Goldilocks economic growth. Low enough to keep inflation down, not so high that central banks stop quantitative easing. Which means ever-lower interest rates. And financial assets keep increasing in value. That means ever-increasing inequality, which keeps wages low and profits high.

Net effect for longer term investors and superannuation funds: the negatives aren’t enough to outweigh the natural tendency for markets to rise.

The trouble with the investment bull case

The above scenario is not improbable. Most of it is a repeat of the last decade.

The problems with the above:

- They are generally dependent on actions by politicians. And more importantly, actions that change the current trajectory.

- Central banks have exhausted most conventional means.

- Governments are generally not supportive of fiscal support.

- Some of the reactions probably need stock markets to fall first – i.e. if stock markets fall then central banks will act, or Trump will ease up on trade demands.

- The trade war is uncovering core issues in China’s economic and political models. These issues will not go away.

- Stock markets are a little expensive.

- Earnings growth is a bit weak.

Under the same conditions with stock markets 25% cheaper, I would be buying stocks.

The problem is the confluence of uncertainty, with a reliance on political outcomes, and little margin of safety in stock market valuations.

The combination is enough to keep us wary. For the moment.

Australian Investment Outlook

The economic plan in Australia seems to be aiming for a short term fillup that will be enough to keep growth ticking over until some form of financial luck strikes. Maybe more Brazilian mining disasters to spike the iron ore price higher. Possibly China to unleash another massive capex stimulus program. Perhaps more earthquakes to shut down nuclear reactors in Japan to send coal and gas prices soaring.

At the moment Australian government’s fillup plan is to try to re-ignite the housing boom by convincing the world’s most indebted consumer to borrow more – a short term win for the Australian economy at the cost of longer-term growth.

This has many obvious pitfalls, but we need to acknowledge it may be successful. Economic luck has been on Australia’s side for the last 15 years, and so maybe Australia will get lucky again.

The danger is that Australia doesn’t get lucky, or more concerning is unlucky.

There are three key factors we are following that will tell us whether the government’s short term fillup is going to work:

Factor 1: Australian Credit growth:

The Royal Commission into banking reversed the credit boom and was enough to see house prices down around 10%. This came even while most other factors affecting house prices were still positive.

Will the Morrison government manage to get the already over-levered Australian households to take on even more debt? If I am too bearish, particularly in the short term, this is where you will see the effects:

On the regulatory front, the Westpac v ASIC responsible lending initial court case win for Westpac is a boost for easy lending conditions. ASIC is taking the case to the Federal court, which will probably limit the upside.

Factor 2: Unemployment

There is not enough space here to go into the detailed links between house prices and unemployment. Indicatively, during the 2012 to 2017 housing boom years, the Perth market faced mostly the same factors as Sydney/Melbourne except for (a) slightly weaker population growth and (b) rising unemployment. And Perth property prices fell more than 10% while the rest of Australia boomed.

We are expecting considerable job losses in the construction sector.

Source: ABS, Seek, UBS

Add to this scenario, job losses from Victorian and NSW state government austerity as budgets have been struck by falling transaction numbers in the housing market.

Also, any global shock (trade wars, recessions, debt crises) is likely to be transmitted to the housing market through higher unemployment.

Factor 3: Foreign Buyers

Foreign demand was substantial for both the boom and the bust:

China cracking down on its capital account and deteriorating relations between Australia and China suggests foreign investment will remain low.

The question is whether Hong Kong unrest translates to increased demand for Australian property.

Asset Allocation

The real question for investment asset allocation is what to do in the meantime. The current government has:

- almost three more years in power,

- plenty of scope to increase government debt to support the housing sector in novel ways

- no compunction about trying to convince Australian consumers to borrow even more.

Blowing the property bubble meaningfully larger is probably beyond the Australian government, but arresting the fall in prices seems likely.

The risk is some sort of global shock or broader economic downturn. Australia has now “broken glass in case of emergency” to prop up the housing market, and policies that could be employed in a crisis have already been applied. In the event of a genuine crisis, the downside is going to be more pronounced.

Which leaves a measure of conflict in asset allocation. Do you try to ride a short term stabilisation in the Australian economy and run the risk that any global crisis is likely to be devastating? Valuations have made part of the decision with the Australian market looking increasingly expensive.

So where does an asset allocator turn?

In 2018 we saw a slowing Australian economy, stagnant wage growth and ten-year government bond yields of 2.8%. We felt being overweight bonds was an easy decision (investors make money on bonds when yields fall).

At the time we were one of the only voices expecting rate cuts in Australia. Now rate cuts are raining down, and further cuts are a consensus opinion.

While we were expecting Australian ten-year bond yields to fall to these levels (1.0%), we weren’t expecting them to fall so quickly. The last 9 months have been dramatic.

Keep in mind that the Reserve Bank of Australia has an inflation target of 2-3%. At current yields, the bond market is suggesting that it will not meet that mandate for the next ten years. Which, in the context of the European and Japanese examples, anemic wage growth, world-leading private indebtedness and an overvalued housing market, is probably a reasonable assumption – unless something changes.

We are of the view that stagnant growth is going to be on the menu until we see governments spending money. And probably “helicopter” money. Given the current state of economics, that will probably take a sizeable economic crisis. Until then, we expect more of the same – slow growth and a grind lower.

The low yields present an asset allocation quandary. I was hoping that by this stage, we would have seen more reasonable equity prices, allowing us to switch out of our bonds and into equities. But equities are looking expensive. Not irrationally expensive, but certainly more costly than we would have thought given the uncertain and low growth outlook. So we are now holding lots of cash, looking for the right opportunity.

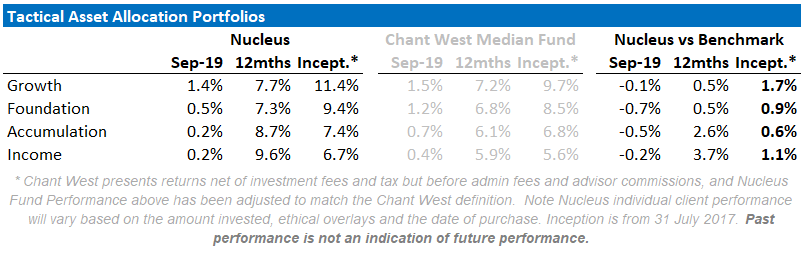

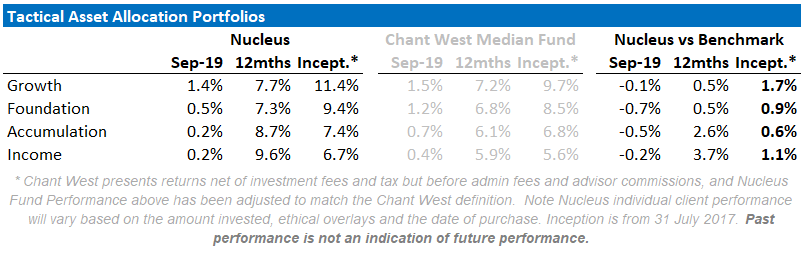

September Performance

We are comfortable with the view that the defensive position is warranted. If markets shoot higher, then we will underperform, but we think the trade-off is justified. Downside protection is more important at this point in the cycle than chasing stock markets higher.

During the month, we re-allocated to several Japanese companies that we believe will benefit from a protracted trade war.

Investment Outlook

Australian shares are still considerably more expensive than most international comparisons with weaker growth expected. We retain large cash and bond balances to hedge against volatility and in the expectation that capital protection will be important during 2019.

Our key focus is on:

- Chinese growth, gauging the extent of the slow down and the policy response to the trade war

- Trying to work out how sustainable the effect of the Australian election will be on house prices

- Gauging the damage that a Boris Johnson led Brexit might cause