I’ve written a few times recently about the imbalances in the Australian economy and how messed up the Australian housing cycle is. It looks as if the Australian economy is hanging on to positive growth based on one factor. Without that factor, there is significant economic downside. The one economic question that matters:

Can rising house prices drive the rest of the economy on their own without a construction boom?

There are three main areas to indicate if this is the case. Two have come out with more negative data since I last posted. One is a glass half empty: better current conditions, worse future conditions.

Upside Case

Can rising house prices drive the rest of the economy on their own without a construction boom?

For the optimists, the answer is a resounding yes. House prices have not only stopped falling but have risen over the last few months. Buyer queues are out the door for limited supply which will inevitably mean rising house prices. And Morrison’s 95% lending for first home buyers hasn’t even begun yet. Investors will follow first home buyers, which will lead prices higher and then upgraders will start buying again. Rising property prices will mean consumers will start spending once more, construction will recommence, and a new Australian economic growth cycle will begin.

It would appear that the Federal Government has this belief.

Downside Case

Can rising house prices drive the rest of the economy on their own without a construction boom?

The poorer arguments mounted by pessimists tend to have a moral angle: house prices are too high for children to afford, they will have to come down to a level that an ordinary person on a regular salary can afford. If that occurs, house prices will fall 30-40%. While these arguments are compelling from a social justice perspective, or on a long term basis, the same arguments have been valid for 15 years. Timing is important:

Other weak arguments base the downturn on extrapolating no intervention from governments. We know the current government is hell-bent on intervening in the housing market.

The better argument is that even if construction approvals rebound, employment would fall for at least another year as the construction decisions made over the past two years affect the number of people employed. And construction approvals are not rebounding.

Rising unemployment in Perth led to a 10% house price fall in the 2012-2017 period while Sydney/Melbourne house prices boomed. What is to stop the same fate for Australia as a whole?

Per capita income has gone nowhere for 7 years, so it is hard to see any rescue coming from that front:

If rising unemployment does mean house prices fall further, then there are a range of probable adverse effects. There are some seriously negative economic effects if the effects snowball. And we won’t even get started about the impact on a fragile Australian housing market if an international shock (Brexit, Trade wars, Hong Kong unrest, corporate debt accidents, European recession) hits.

It doesn’t need to be one or the other

You don’t need to buy into the entire negative story to be cautious. If employment holds up, then the positive story has a chance (assuming benign international conditions). But, if unemployment rises, then Australia won’t need a global shock to see house prices resume a downward path.

When presented with an asset class that has limited upside in positive scenarios and significant downside in adverse scenarios, I usually opt to avoid the asset class and look for returns elsewhere.

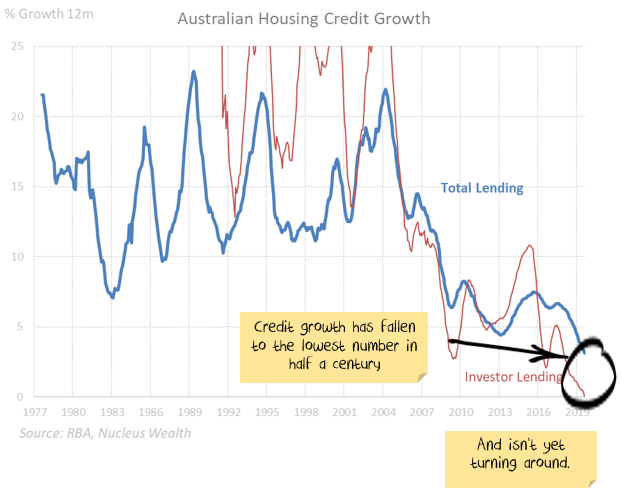

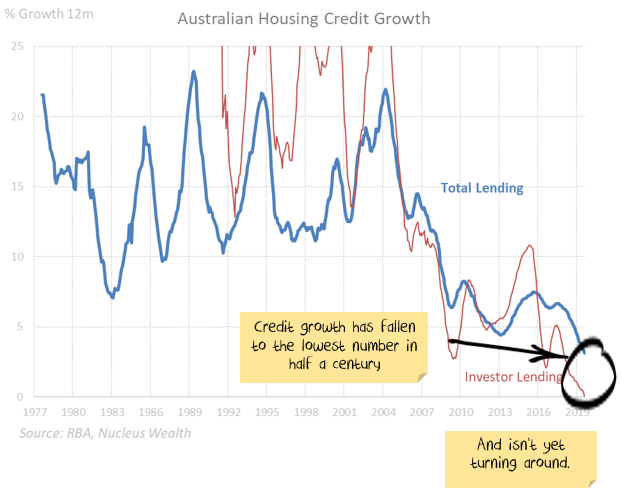

Update 1: Australian Credit growth:

The Royal Commission into banking reversed the credit boom and was enough to see house prices down around 10%. This came even while most other factors affecting house prices were still positive.

Will the Morrison government manage to get the already over-levered Australian households to take on even more debt? If I am too bearish, particularly in the short term, this is where you will see the effects. So far there are none:

On the regulatory front, the Westpac v ASIC responsible lending court case win for Westpac has the potential to lead to easy lending conditions. ASIC is taking the case to the Federal court, so we are in limbo for some time.

Update 2: Unemployment

There is not enough space here to go into the detailed links between house prices and unemployment. Indicatively, during the 2012 to 2017 housing boom years, the Perth market faced mostly the same factors as Sydney/Melbourne except for (a) slightly weaker population growth and (b) rising unemployment. And Perth property prices fell more than 10% while the rest of Australia boomed.

We are expecting considerable job losses in the construction sector.

Having said that, construction jobs have been resilient so far. Forward indicators (job ads and approvals) continue to point to sizeable job losses.

Source: ABS, Seek, UBS

Add to this scenario, job losses from state government austerity as budgets have been struck by falling transaction numbers in the housing market:

Finally, any global shock (trade wars, recessions, debt crises) is likely to be transmitted to the housing market through higher unemployment.

Update 3: Foreign Buyers

Foreign demand was substantial for both the boom and the bust:

China cracking down on its capital account and deteriorating relations between Australia and China suggests foreign investment will remain low.

The question is whether Hong Kong unrest translates to increased demand for Australian property.

The Answer

So, the answer to the one question

Can rising house prices drive the rest of the economy on their own without a construction boom?

will be found in whether increases in unemployment remain contained.

I’m skeptical. But if I’m wrong, the charts above will be where we will see the signs.

Recent data suggest my skepticism is warranted.