Stock markets started to slide in April and have accelerated to the downside in the early days of May. Commodities continue to be the main story, tremendously volatile. Over the last 12 months, iron ore more than halved, then added 50% and is now falling. Oil and gas have been similarly volatile. From here, there are some serious questions to be asked of commodities and therefore the exposure to Australian stocks.

The glass-half-full story is that the Ukraine invasion and Russian sanctions will benefit Australia. Australian exports of iron ore, wheat and gas will replace Ukraine and Russian exports, commodity prices will remain high and the ASX will continue to boom.

The glass-half-empty story is that Russian iron ore, oil and wheat will go to India and China rather than Europe, creating short term issues, but merely a reshuffling of supply in the medium term. Spiking gas prices are a short term positive, but have accelerated the move to renewables – a medium and long term negative.

Our concern is that central banks are suggesting that they will solve inflation problems, which are largely a result of supply chain issues, by restricting demand. This is not an attractive setup for markets.

We expect international equities to provide some protection from a growth slowdown. While the Aussie dollar is likely to rise if the energy crisis worsens, it is more likely to fall over the medium term. This will hedge the downside under the worst scenarios, whilst still providing some upside in the better ones.

Adventures in economic engines

I have a confession. I don’t know much about the inner workings of combustion engines. Starting combustion engines, I know a lot about. Almost half a century of lawnmowers will do that for you. And being a cash-strapped student in the late 80s and early 90s. I know how to prime an engine. Use a choke. Stop an engine from flooding. Push start a car. Jumpstart a car. The experience of many Gen Xers is similar, I’m sure. 90% of the problems come from starting the engine. If you get that right, the rest of the system usually runs itself. You can (mostly!) survive without knowing how the engine works.

I suspect many central banks feel the same way about the economy. They know how to restart it: lower interest rates, increase government spending, loosen lending standards, boost consumer debt. But, they simply hope that the engine keeps running the rest of the time. And, much like the mysterious combustion engine, mostly it does!

However, every now and again, problems emerge. And it seems likely that we are in that position now. Debt levels are already high. Stall speed approaches.

A decade of weak demand, “solved” by a pandemic

From 2010 until the pandemic, central banks struggled to get enough demand. Inflation was muted. Interest rates spent a decade in the doldrums. Then, the pandemic hit, and the mix of increased spending on goods plus direct government stimulus gave us a boom.

The question is whether:

- the demand problem has been “solved” by the stimulus and now run-away inflation is the problem or

- we have a supply problem, exacerbated by short term government demand stimulus

If the answer is the first, central banks are on the right path. If the second is true (and I think it is), an accident is brewing.

Supply chain problems take centre stage

Inflation spiked in 2021. In my view, mostly due to clogged supply chains. By the end of 2021, supply chain problems were easing. Then the world economy was hit by Russia invading Ukraine. Energy prices rocketed. China began another round of lockdowns.

Now, we are facing further supply chain disruption for much of 2022.

Global banks are going to squash demand

The response from central banks has been to signal that they are going to slam on the brakes. The expectation is that central banks are going to beat demand down to the level of supply. At the same time, governments have hauled on the park-brake. We have a record amount of government stimulus being withdrawn from the market.

The Australian central bank, in particular, promised to be “data-driven”, stop relying on wage growth forecasts (which had proven hopelessly optimistic) and wait for actual wage growth. They promised no rate rises until 2024. Both promises have been thrown out the window.

This all may be the right policy for constraining inflation. Maybe world demand needs to be beaten down to much lower levels. But, it is not a good recipe for investment.

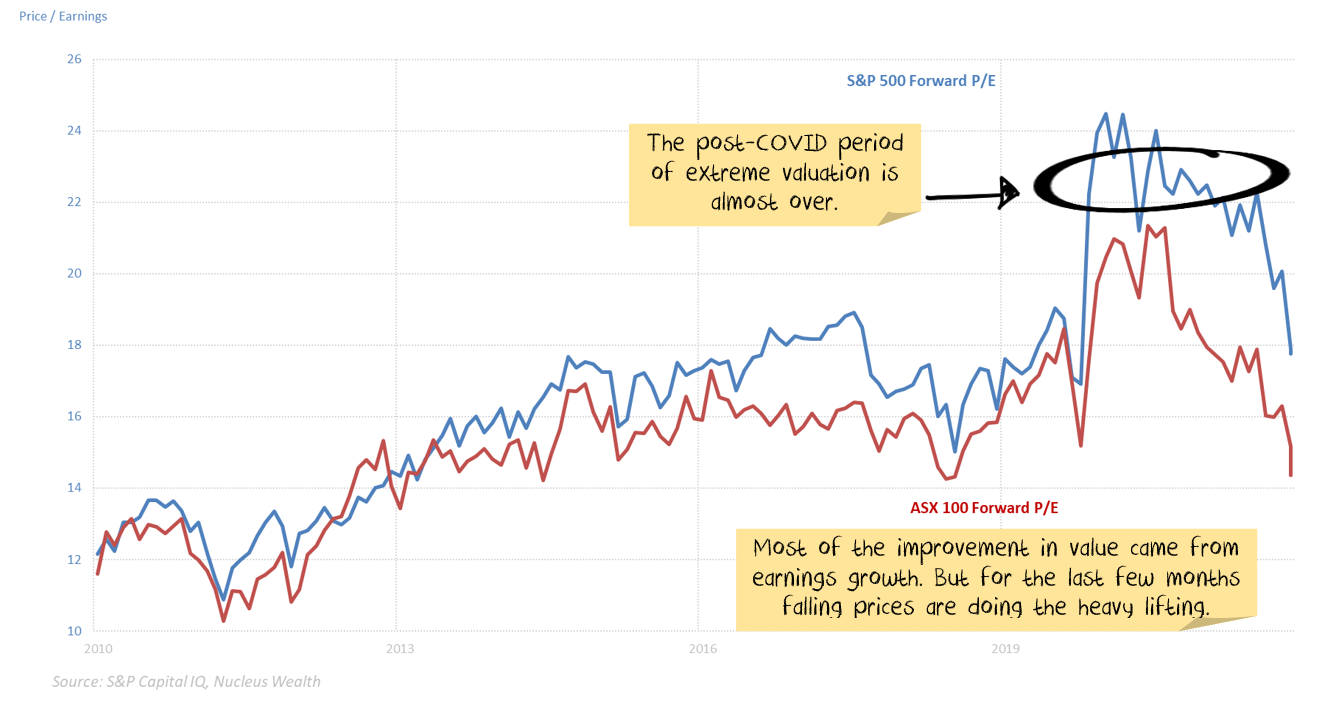

Valuation excesses have disappeared

We have been underweight stocks with the expectation that an accident was brewing. It looks as though that accident is arriving.

In the first few months of 2022, the valuation premium from the pandemic has disappeared:

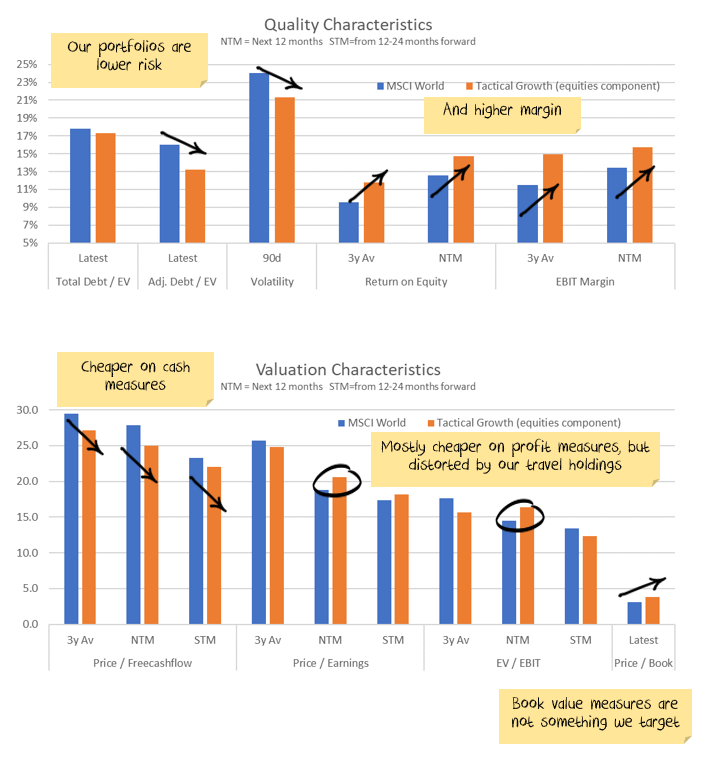

Markets are still not cheap. But they are no longer horrendously expensive.

Earnings growth is the most important factor

Valuation does matter. But earnings growth matters more. In a good year, earnings can easily grow 20% or more, making an expensive market fair value.

The danger is that earnings can also fall quite precipitously. And today, in my assessment, that is where the danger is.

At an aggregate level, earnings growth still looks OK. But most of the growth in the last reporting season came from energy and resources. And, effectively, central banks have promised to kill commodity prices to bring down inflation.

Second, we have had a record move in longer-term interest rates. These typically take six months to flow through to the real economy. The clock is ticking.

Business surveys have already turned down.

Stock markets have started to price the change. It is not yet time to buy.

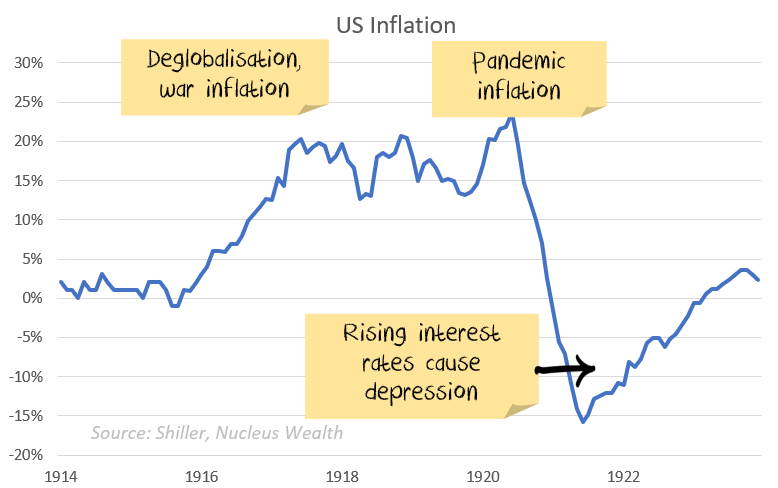

Have we seen this all before?

- Globalised supply chains reversing into more local production due to geopolitical tensions

- A pandemic disrupting supply chains

- A surge in inflation due to supply issues

- Central banks hiking rates into a supply-side shock

Yes, we have. Following World War I, all of the above factors were in place.

By 1920, inflation in the US was running at 15%. The US central bank hiked rates from 3.5% to 5.6% to curb demand. By 1921 the US was in a depression, with inflation of -10%.

The analogy is not exactly the same. But, trying to use interest rates to solve supply chain problems is at the core. There are more similarities than there are differences.

Investment Outlook

I have some pretty clear ideas about which trends are sustainable and which ones aren’t in the long term. However, the short term is far less clear:

- The sanctions on Russia are unlikely to be lifted anytime soon. The short term effect is probably commodity shortages. In the longer term, it seems likely that we will see a re-orientation, Russia will supply more to countries like China and India, less to Europe. For some commodities (oil, wheat) this will be easier. For others (gas) it will be extremely difficult.

- The Omicron variant looks to be resolving in the direction we expected, ripping through economies without too much harm and leaving behind an acceptance that COVID is endemic.

- The geopolitical energy crisis in Europe has turned acute. This will subtract from European growth in the short term, there will be a rush to alternative energy sources in the long term.

- Supply chains have improved a little but are still clogged.

- Demand is challenging to read and distorted by Omicron. Demand held up far better than prior virus waves.

- Governments continue to withdraw (or not replace) stimulus. There will be a fiscal shock in 2022. The question is whether the private economy will be strong enough to withstand it.

- Central banks have made it clear that they will try to solve the Russian induced energy issues and supply chain induced inflation by raising interest rates. The odds of a policy error have increased significantly.

- China still has not bailed out the property sector. China is trying to ensure that houses under construction get built, small businesses have access to credit, infrastructure building continues, and failing developers do not crash the economy. But China is yet to show any signs of turning back to the old days of debt-driven property developer excesses. Unless they change, this will deflate the commodity market.

It is still not the time for intransigence. Events are still moving quickly. But we have positioned the portfolio towards the most likely outcome and are gradually increasing the weights as more data arrives.

Bond yields have risen significantly. If the world heads for recession this is a buying opportunity. The problem in the short term is that the narrative “high inflation, central banks raising rates = sell bonds” is surging still. And the mix of higher volatility, leading to deleveraging of risk parity trades, and momentum means yields could yet go higher. We are starting to invest for bond yields to reverse.

Bond Mea Culpa

We clearly held too much in our bond portfolio during the first few months of the year. We had a market weight position in most of our funds, a little more in our growth portfolio.

Bonds then suffered one of the worst investment periods in their history, down a little over 10%.

The net effect is that we do not believe that economies are strong enough to handle interest rates that are 3% higher. The market disagrees. We are starting to move overweight into bonds with the view that interest rate markets have sown the seeds of their own demise.

I will publish a longer piece later this week to go into more detail.

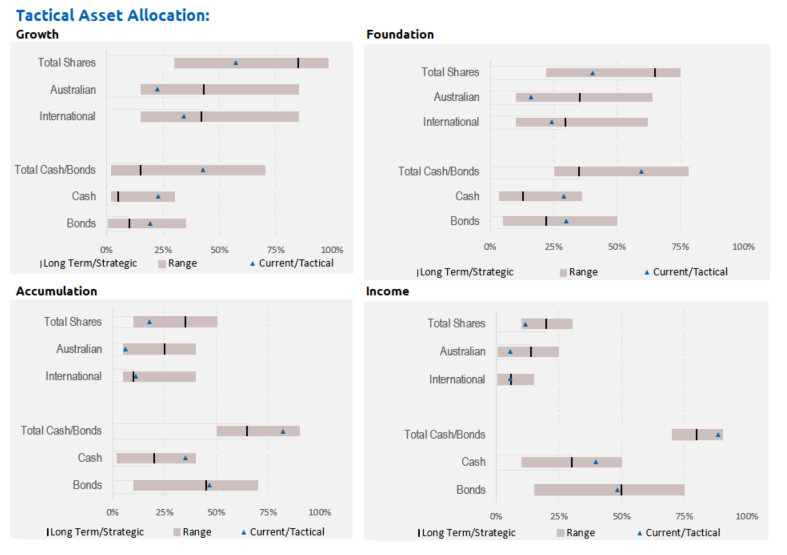

Asset allocation

Stock markets are expensive, but becoming less so. Debt levels are extremely high. Government/central bank support continues but is slowing. Earnings growth had been really strong but has come to a halt.

Markets are supported to a great degree by central banks and governments. Policy error is every investor’s number one risk.

But, any number of other factors could force this off course and see unexpected inflation. Mutations could disrupt supply chains again. Chinese/developed world tensions might rise further, leading to more tariffs. Or, China might reverse its tightening on property sectors. Biden may get through additional stimulus, driving increases to minimum wages.

We are significantly underweight Australian shares, with the view that the Australian market will be the one most affected by a slowdown in China:

Australian equities have been a good source of investment performance in recent months. We switched out of them and into international equities and cash. We have largely built the defensive side of the portfolio up, changing out of value winners like resources, banks and cyclical industrials.

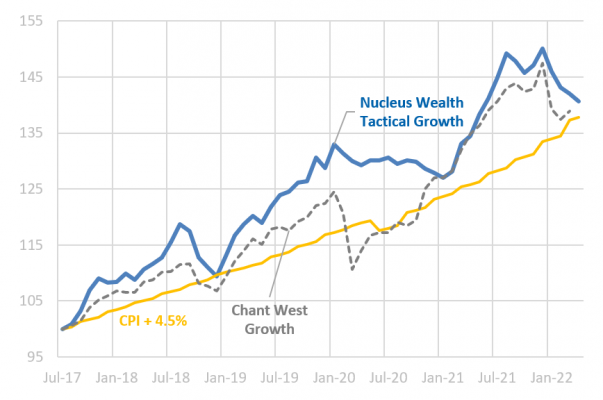

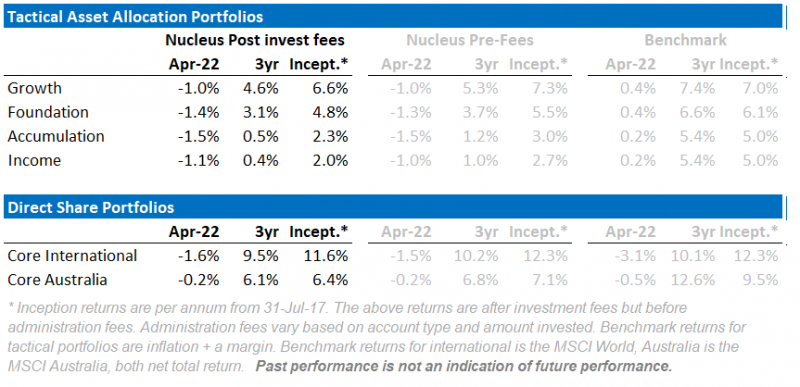

Performance Detail

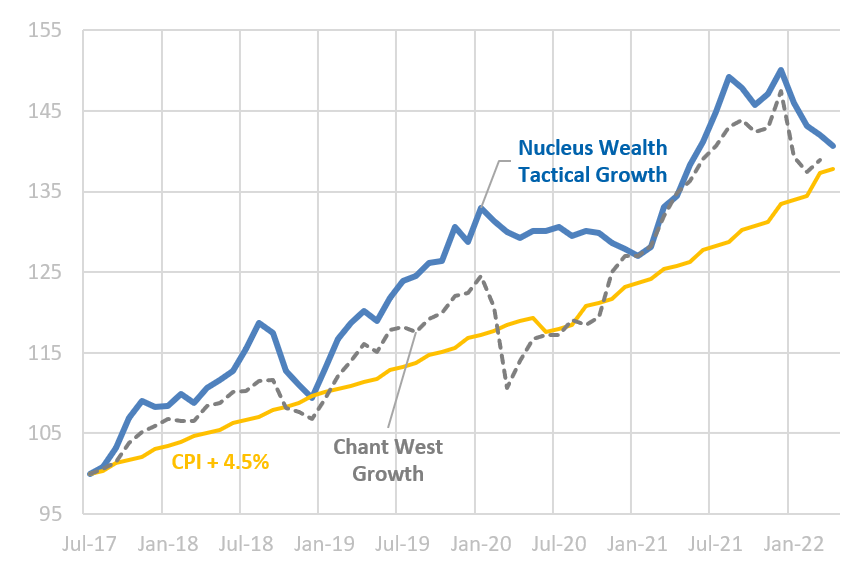

Core International Performance

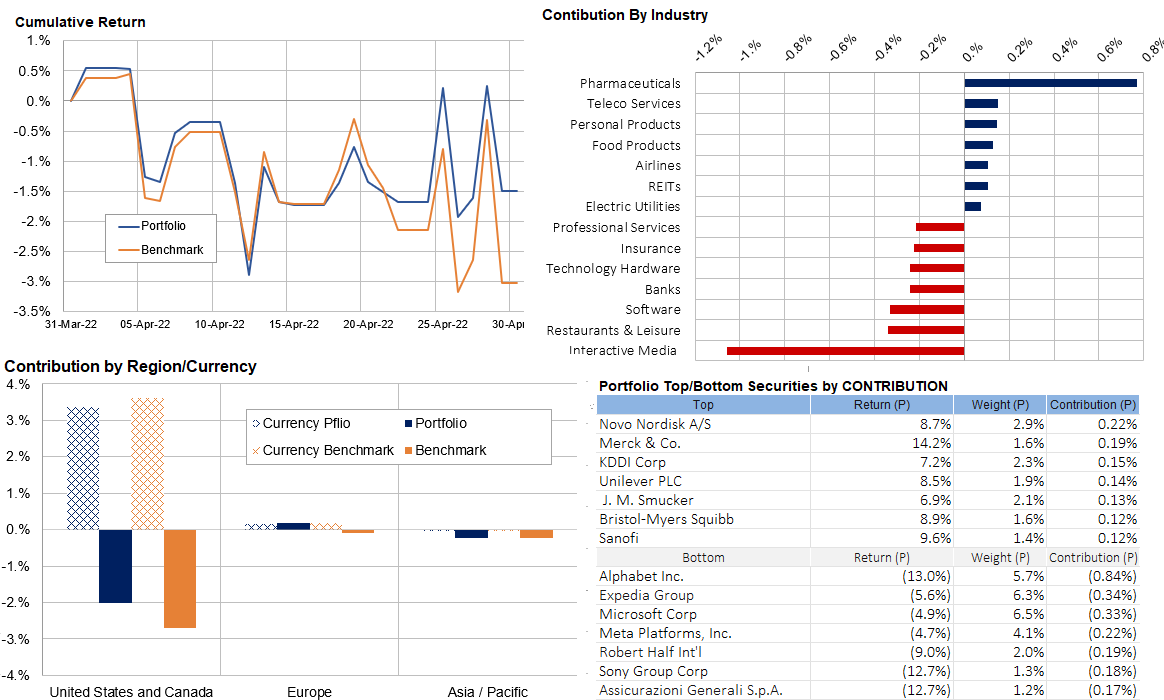

Markets drifted lower in a very volatile month with our portfolio outperforming largely on the back of strong pharma performance and a lower weighting to the unloved tech sector. AUD weakness meant currency tailwinds reduced the potential falls. During the month we largely stayed the course making no major changes to the portfolios.

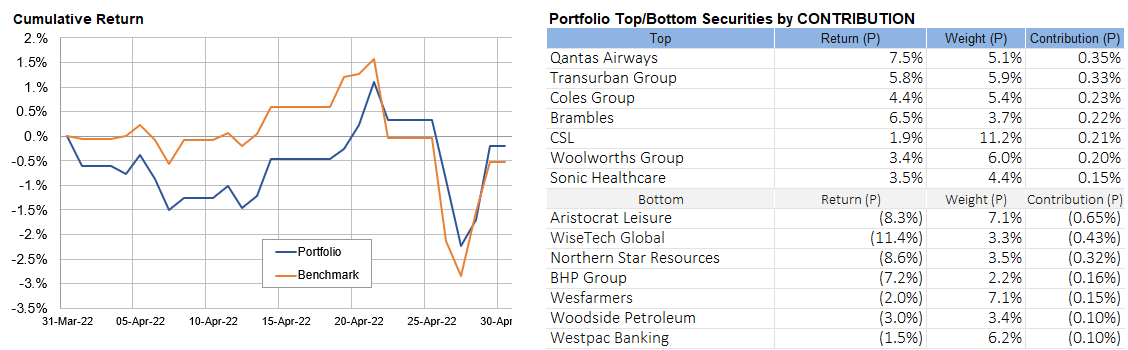

Core Australia Performance

Defensives were the place to hide in April while growth and resource stocks fell back. Our relative underweight to resources meant we outperformed the Benchmark. No portfolio changes this month.