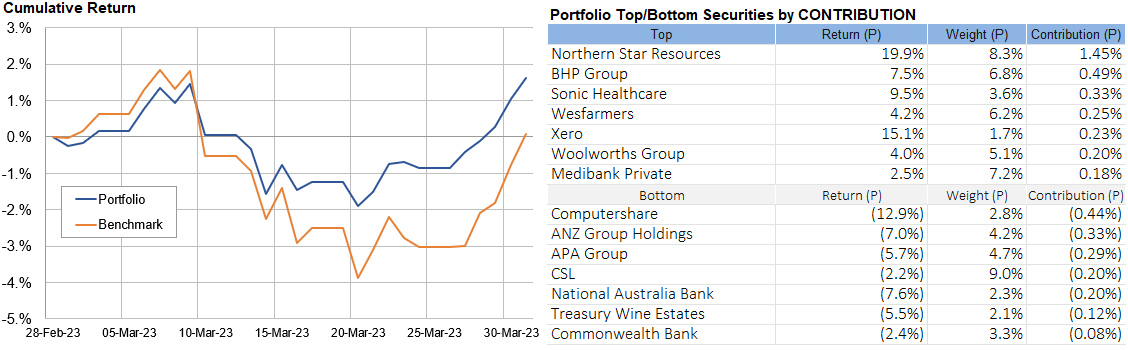

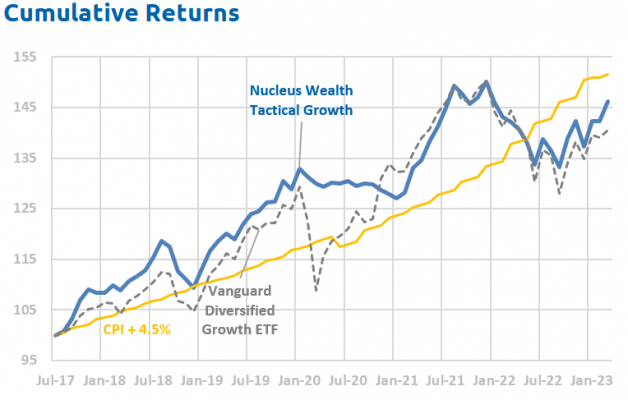

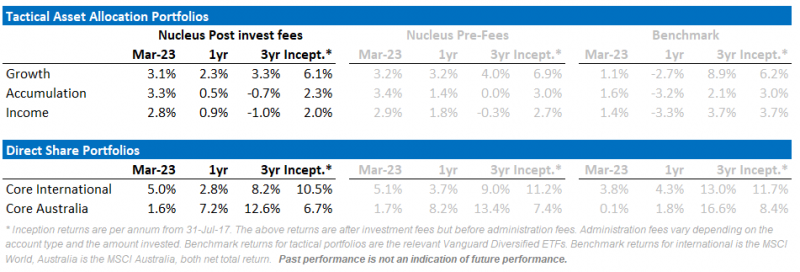

During March, all of our portfolios outperformed their benchmarks, bolstered by our defensive and underweight bank stock exposures. Quality and growth stocks boomed, banks fell. The ASX fell slightly but our Australian portfolio rose 1.6% and our international rose 5%. Bonds rose around 3.5%.

Looking forward, we expect weak stock markets as the central banks raise rates to slow demand, shrinking company profits.

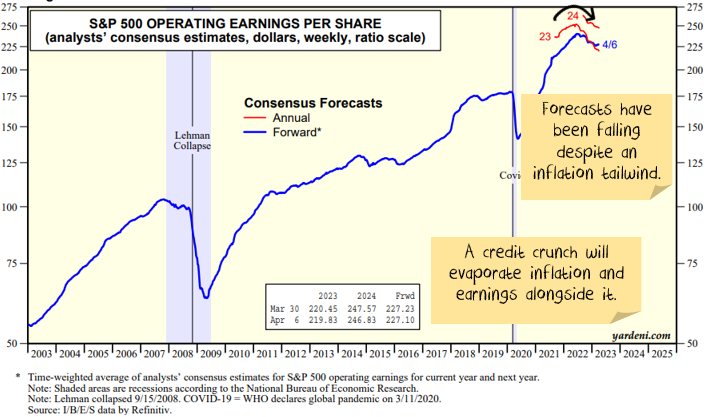

With that in mind, the key factor to watch in the coming months to tell if we are wrong or right is the change in corporate profitability. The recent reporting season in the US showed some signs of weakening earnings, but not enough to confirm our thesis yet. Earnings continued to be downgraded over March, but not significantly.

The sectors to buy for the next up-cycle

Today I want to talk about what the other side of the downturn will look like. Not because I think the downturn is over. In fact, the signs are increasingly pointing towards a continued acceleration of the credit crunch. But, the time to plan your portfolio is not as earnings are being hit and companies are falling over. You need a game plan now. And recent advances in artificial intelligence could be a game changer.

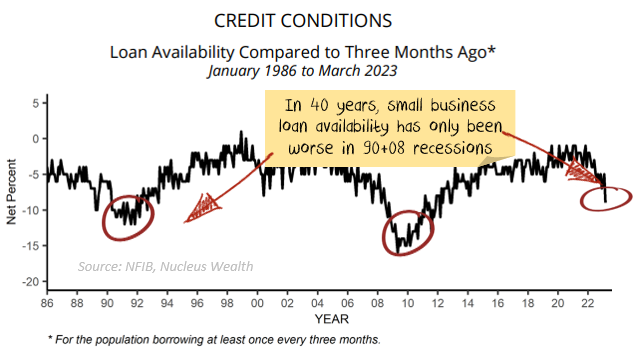

The credit crunch is here.

I feel like I have done this topic to death recently. The short version:

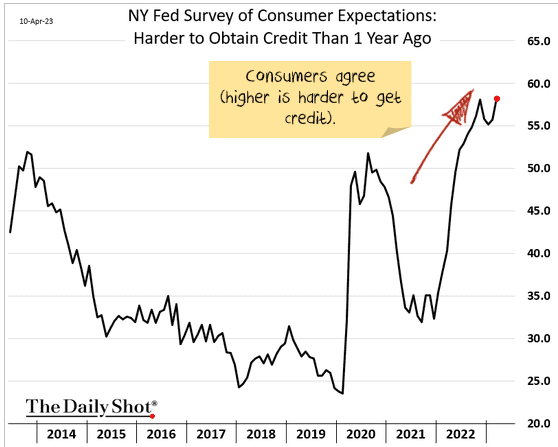

A banking crisis has been playing out over the last few weeks. On its own, it is unlikely to create major issues. The credit crunch following the banking crisis will create the major issues.

I’m expecting bank funding costs to increase. Deposits to flee the smaller banks. Both have already started.

As a consequence, banks scale back their lending. Interest rates charged are higher. Corporates bear the brunt, the US falls into recession and default rates spike. Inflation is no longer a concern.

Net effect: a mini-banking crisis, followed by a credit crunch, possibly followed by a traditional banking crisis.

Some quick stats:

Earnings are still too high. As are valuations.

One of the key features of the last year has been the ability of companies to expand margins, using inflation as a cover to push through price increases. But that is coming to an end.

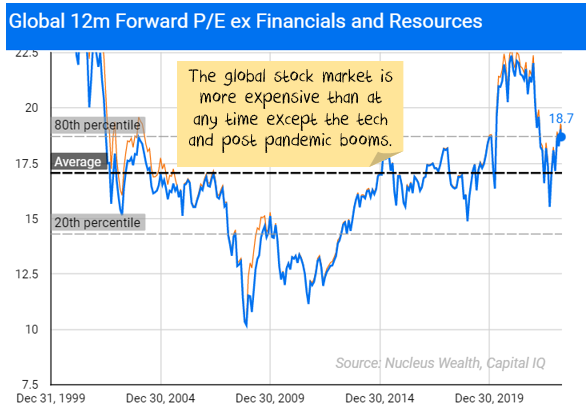

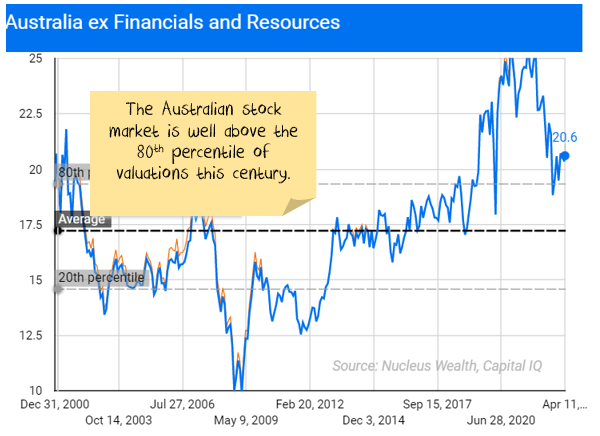

It is more instructive to strip out banks and resources on the valuation front, as their earnings can be volatile. On that basis, global stocks have only been more expensive during the tech bubble and the post-pandemic boom. Australian stocks are more expensive again.

What type of economic environment are we headed for post-recession?

The major swing factor will be government reactions to the recession. If there are significant direct fiscal interventions, as we saw during the pandemic, then inflation might return.

More likely, it will be a replay of the 2010s:

- High levels of inequality mean not much demand (the rich save extra income).

- Central banks cut interest rates, hoping already leveraged consumers could take out even greater loans.

- Productivity gains don’t end up in wages.

- Inflation stays low.

Inequality is here to stay for a while. In Australia, a left-wing government is increasing tax on low and middle-income earners while cutting the tax paid by the top brackets. It is similar globally. There are no signs of any broad backlash.

The artificial intelligence game-changer.

The biggest potential positive for earnings is coming through artificial intelligence breakthroughs.

I’ll leave the details of how the software works and what is different for others. There are plenty of breathless newspaper reports discussing the pros, cons and hyperventilating about the demise of jobs. This is partly because it is true. Mostly because it is the journalists themselves that are in the firing line this time.

What I will note is

- Chat GPT, in particular, has made significant inroads into democratising artificial intelligence for a broader audience.

- Arguably, Chat GPT’s greatest input has been a user-friendly interface.

- The sudden introduction of artificial intelligence to hundreds of millions of people is bound to have significant productivity gains.

- The volume of people now using these models will accelerate the learning and improve the models themselves. Meaning more productivity gains.

- The difference vs the 2010s, for an investor, is that this time it is the service industries that look like they will benefit the most from the productivity gains. Or lose the most from job losses. Depending on how you want to frame it.

Productivity tools mean fewer assistants.

Fifty years ago, most professionals had a secretary. By the late 1980s, word processors replaced typewriters, and the ratio of assistants to professionals shrunk. Into the 1990s and the rise of email took another chunk. The internet, scheduling apps and online bookings meant fewer again. Productivity tools meant doing more with less.

It is the same with artificial intelligence. The lawyer doing the work is still needed. But they won’t need as many juniors to chase up precedents or re-draft contracts.

The senior software engineer will still create the program – but artificial intelligence will limit the ancillary roles like testing, porting into other languages, and error trapping. Artificial intelligence will perform the basic tasks that could be offloaded to offshore staff or a junior.

Copyrighting is not a job that I would be steering my kids towards. There will be an explosion of derivative content on the internet. A role that artificial intelligence is eminently suited for. The task of writing is suddenly much easier. Original thoughts will still be at a premium, but very little of the world runs on those anyway.

The factory analogy.

Talking of thoughts that are not mine, I heard a great analogy. Back in the day, factories were powered by steam engines. This meant that factories were often multistorey, designed to be as close to a central engine as possible.

Once electricity arrived, companies replaced the steam engine but left the rest of the factory in place. It took a while before people realised that distributed power meant they were no longer constrained. At this point, they redesigned factories around the process rather than the power source. We ended up with huge, long factories where inputs come in at one end, more efficient operations in the middle, and finished goods at the other.

Using artificial intelligence is the same. Right now, we are replacing existing systems. There will be productivity enhancements that we have yet to think of.

The investment question: who will benefit most.

To the victor, the spoils.

In different industries, different groups will benefit the most. There are four main possibilities to consider for each industry:

1. Artificial intelligence technology companies.

The technology producers like Open AI, Microsoft, Google will benefit. But I expect them to distribute it free or close to free in the early stages. Probably for the mid-term as well.

The reason why is that it is a land grab. The benefit of having more users outweighs the benefit of charging too much for the software – a lot like search.

Say you have the greatest AI engine right now, and you charge 50 bucks a month for it. You get a million users.

However, your competitor gives it away free with a product only 80% as good as yours. They get a billion users.

Now, they are collecting 1,000x your data, improving their engine and eventually leapfrogging your technology.

For this reason, I’m expecting the competition to be fierce. These companies will benefit but won’t take the lion’s share of the productivity gains.

2. High-value employees.

The next probability is that the senior, more productive employees will demand higher salaries as the juniors are let go. In smaller service companies, say doctors or lawyers, the more efficient professionals might try to take most of the gains in higher wages.

The larger the workforce, the less likely this is to occur. At the margin, productivity gains will likely lead to above-average wage growth for top employees. But not enough to make a huge difference in company profits.

At an economy-wide level, the job losses and devaluing of basic service jobs will probably be bad for wage growth and equality.

3&4. Prices or company profits?

What happens to the rest of the productivity gains? In competitive industries, most of it will end up in lower prices for consumers as the gains are competed away. In less competitive industries, the gains end up as higher profits.

Say you are a phone company. You cut call staff by a third, but so does everyone in your industry. Do you all make higher profits? Or are the gains competed away in lower prices. History says the second.

History suggests that profits will be the primary beneficiary for companies with more pricing power, say Apple or Coca-Cola.

So, what do you buy?

Value stocks broadly are not going to be the winners. They tend to be the stocks with the least pricing power. Productivity gains will be competed away for most value stocks.

Growth stocks? Maybe. It will be hit-and-miss with this group due to changing business models. But, given we are talking about stocks to buy as economies recover from the recession, it will be worth having some growth in your sights for at least the initial stages of the recovery.

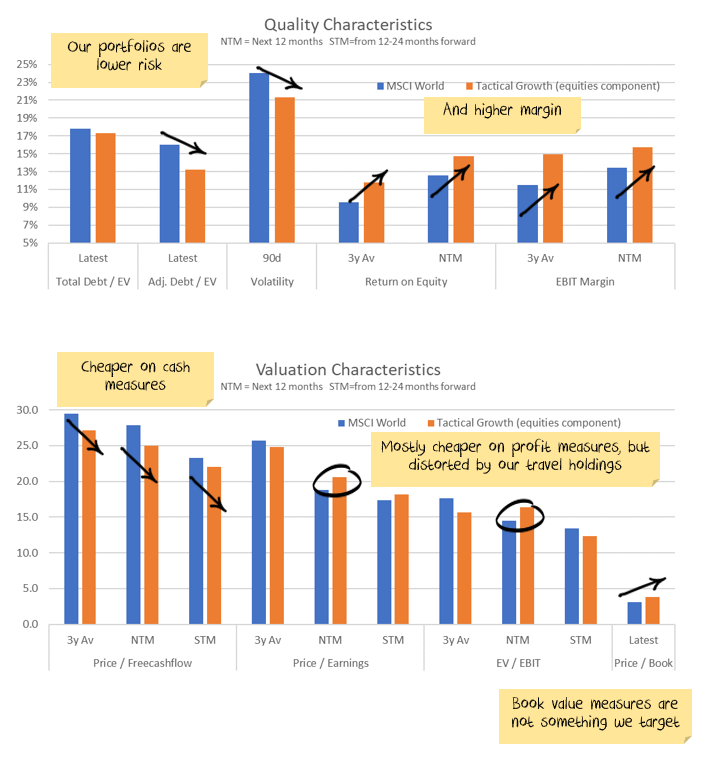

Quality stocks are the safer bet in many cases. These are the stocks with pricing power, higher margins and better returns on equity.

I would be careful buying intermediaries or wholesalers. The internet has spent the last 20 years trying to disintermediate these companies. Any surviving companies should be worried that improved access to artificial intelligence will finish the job.

With that framework, let’s dig through the most affected sectors:

Information Technology is the obvious place to start. Coders are going to be much more productive. You will need fewer of them. Support services will generate cost savings for companies, and job losses for employees, for years.

Media is going to see significant changes. Advertising and copyrighting will have their staff numbers halve for the same output. Media creation, will become cheaper and easier. This is already affecting music and video as well as text. Do you need to churn out a mindless rom-com or action movie? The number of staff you need will be much, much lower. Talent will still win, but your talent will need less help.

Legal & compliance, and likely costs, are in for a shakeup. You will still need the clearer thinkers, and they will still be well compensated. But it will be less about armies of lawyers than it once was.

Transport is on the cusp of a major change. Logistics will be a major beneficiary. Driverless trucks and cars will generate a productivity boom like no other. Whether driverless vehicles will be ready next year or in fifteen years is hard to tell. What I can say is broader access to artificial intelligence will speed up the process.

Education is in for a shock. No more take-home assignments? Faking competence is suddenly so much easier. Something will need to change.

Healthcare is also ripe for disruption. Diagnosis tools will make doctors significantly more productive. Wearable technology is generating reams of new data. Research and development tasks are going to be so much easier. Does that end up in cheaper healthcare or simply more of it and higher-paid doctors?

Finance will continue to see job losses in customer service roles. In corporate finance, stock broking and funds management, the rainmakers will be more productive and need less support staff.

Wrap up

Keep in mind that all of these changes are longer term. We have a credit crunch to navigate first.

But we can clearly see where the next wave of productivity enhancements comes from. And they will likely underpin reasonably significant earnings growth after the credit crunch.

Investment Outlook

I have some pretty clear ideas about which trends are sustainable and which ones aren’t in the long term. However, the short-term is far less clear:

- The banking crisis is morphing into a credit crunch. This is the number one issue over the next few months.

- The sanctions on Russia are unlikely to be lifted anytime soon. The short-term effect was commodity shortages. In the longer term, it seems likely that we will see a re-orientation, Russia will supply more to countries like China and India, less to Europe. For some commodities (oil, wheat) this will be easier. For others (gas) it will be extremely difficult.

- The Omicron variant looks to be resolving in the direction we expected, ripping through economies without too much harm and leaving behind an acceptance that COVID is endemic. In China, rolling lockdowns have finally finished.

- The geopolitical energy crisis in Europe has eased on the back of much warmer weather. Australian energy price caps have pushed down energy prices. There will be a rush to alternative energy sources in the mid-term.

- Supply chains continue to improve.

- Governments continue to withdraw (or not replace) stimulus. There will be a fiscal shock into 2023. The question is whether the private economy will be strong enough to withstand it. Leading indicators suggest profits will be lower.

- Central banks have made it clear that they will try to solve the Russian-induced energy issues and supply chain-induced inflation by raising interest rates. The odds of a policy error have increased significantly.

- China still has not bailed out the property sector. The latest changes are not a bailout… but they may morph into one. China is trying to ensure that houses under construction get built, small businesses have access to credit, infrastructure building continues, and failing developers do not crash the economy. China is yet to show any signs of turning back to the old days of debt-driven property developer excesses. In the short term, commodities have been booming. If China doesn’t continue to roll out new measures, the commodity market will deflate again.

It is still not the time for intransigence. Events are still moving quickly. But we have positioned the portfolio towards the most likely outcome and are gradually increasing the weights as more data arrives.

Bond yields have risen significantly. If the world heads for a recession this is a buying opportunity. In the short term the narrative “high inflation, central banks raising rates = sell bonds” seems to be coming to an end. Although there may be another last hurrah as the US central bank looks to rein in the stock market optimism.

And the mix of higher volatility, leading to deleveraging of risk parity trades and momentum means yields could yet go higher. We are invested for bond yields to reverse.

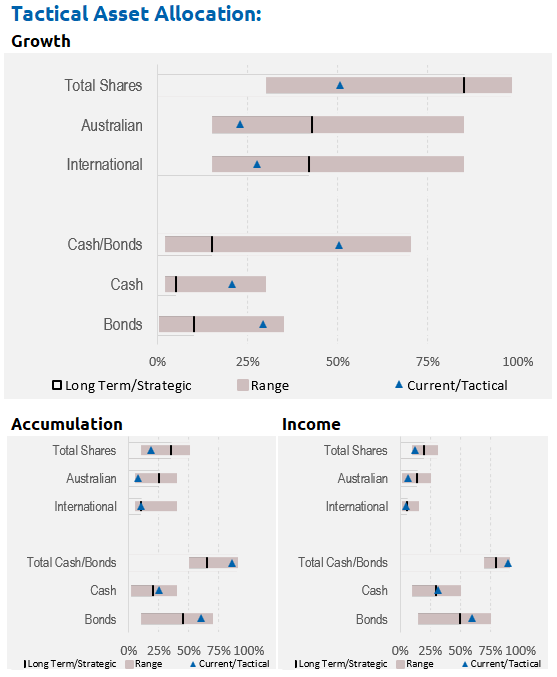

Asset allocation

After being very expensive for a number of years, stock markets are now merely expensive. Debt levels are extremely high. Earnings growth had been really strong but has come to a halt. There are signs it is starting to reverse.

Markets are supported to a great degree by central banks and governments. Policy error is every investor’s number one risk.

But, any number of other factors could force this off course and see unexpected inflation. COVID mutations could disrupt supply chains again. Chinese/developed world tensions might rise further, leading to more tariffs. Or, China might reverse its tightening on property sectors.

We are significantly underweight Australian shares, and as noted above, overweight bonds, with the view that the Australian market is more quickly affected by rising interest rates and more affected by a global recession:

Performance Detail

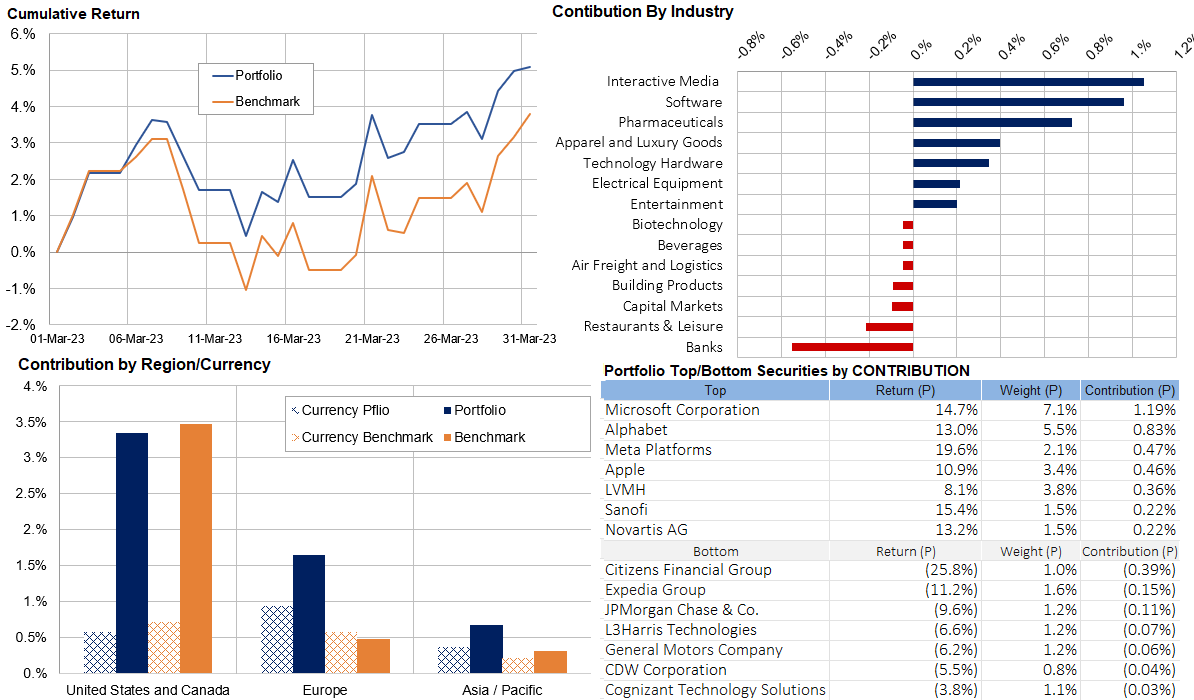

Core International Performance

March was a good month for global equities but especially the US markets. While there were currency tailwinds these were minor relative to what we have seen over the quarter. Pleasingly our portfolios outperformed their benchmarks in all geographic regions with Europe the stand-out. Luxury goods and Pharmaceuticals in particular had a strong showing. Unsurprisingly given the banking turmoil our one regional US bank exposure was the key detractor but our overall underweight banking stance kept us in good stead relative to the market. We positioned ourselves more in defensive stocks throughout the month, buying Defence Contractors, Tobacco and top-end Alcohol providers.

Core Australia Performance

Australian equities had a lackluster month driven primarily by the global weakness in Bank stocks that constitute a large portion of our benchmark. Being significantly underweight banks meant that our Australian portfolio outperformed again relative to the local market. Our significant gold exposure was the primary contributor as gold rallied. No changes were made this month.