Last week, ABC’s Ian Verrender published an article on the “productivity conundrum” preventing the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) from cutting interest rates.

“Like many other developed countries, our productivity growth has gone down the shoot”, wrote Verrender.

“In many ways, ours has been even worse”.

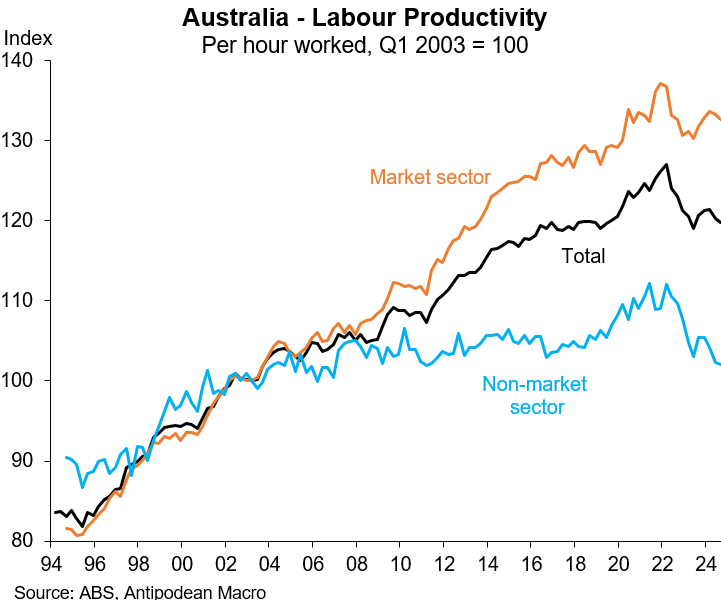

“Back in 2003, Australian labour productivity was averaging around growth at about 1.8% a year and remained that way until about 2015”.

“By the time the pandemic rolled around, it had dropped to 1.2%. Now, it’s tracking at an anaemic 0.8%”.

“Which raises the question: Have we become a bunch of lazy no-hopers who refuse to go the extra mile?”, Verrender said.

Verrender identifies the commodity boom, which hollowed out the manufacturing industry, as the primary driver of Australia’s productivity decline:

“A high Australian dollar made our trade-exposed industries less competitive”, University of Technology professor Roy Green told Verrender.

“This particularly affected manufacturing, historically the major source of increasing productivity. Manufacturing was only just finding its feet in global markets after the tariff reductions of the late 1980s and 90s”.

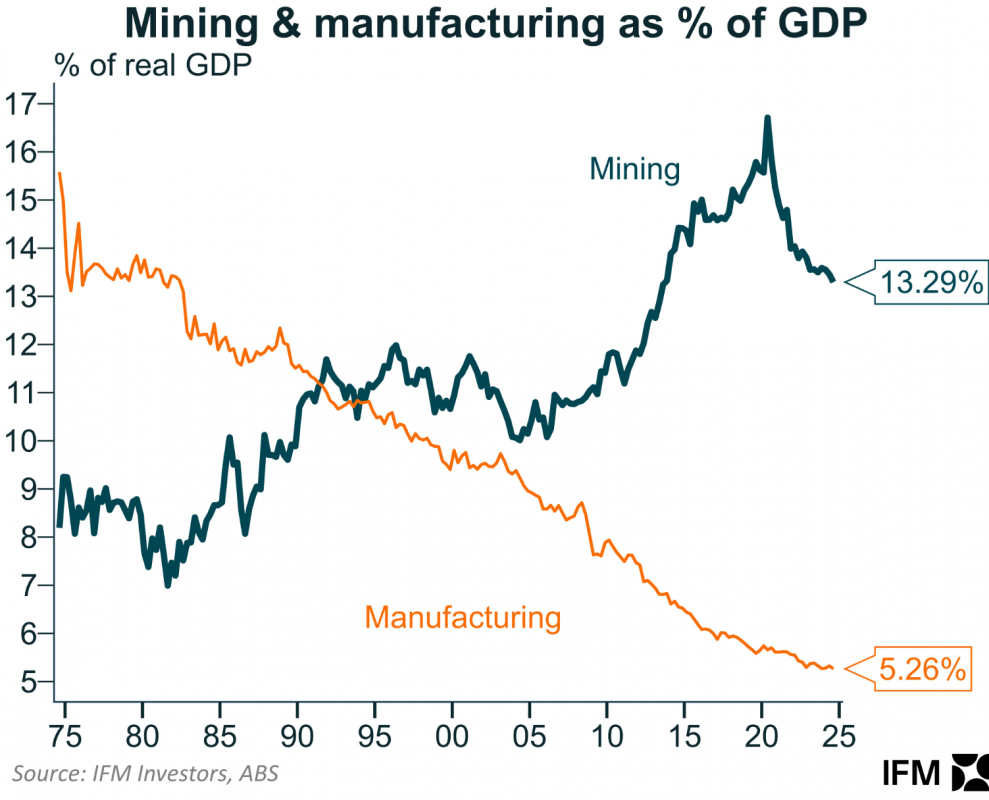

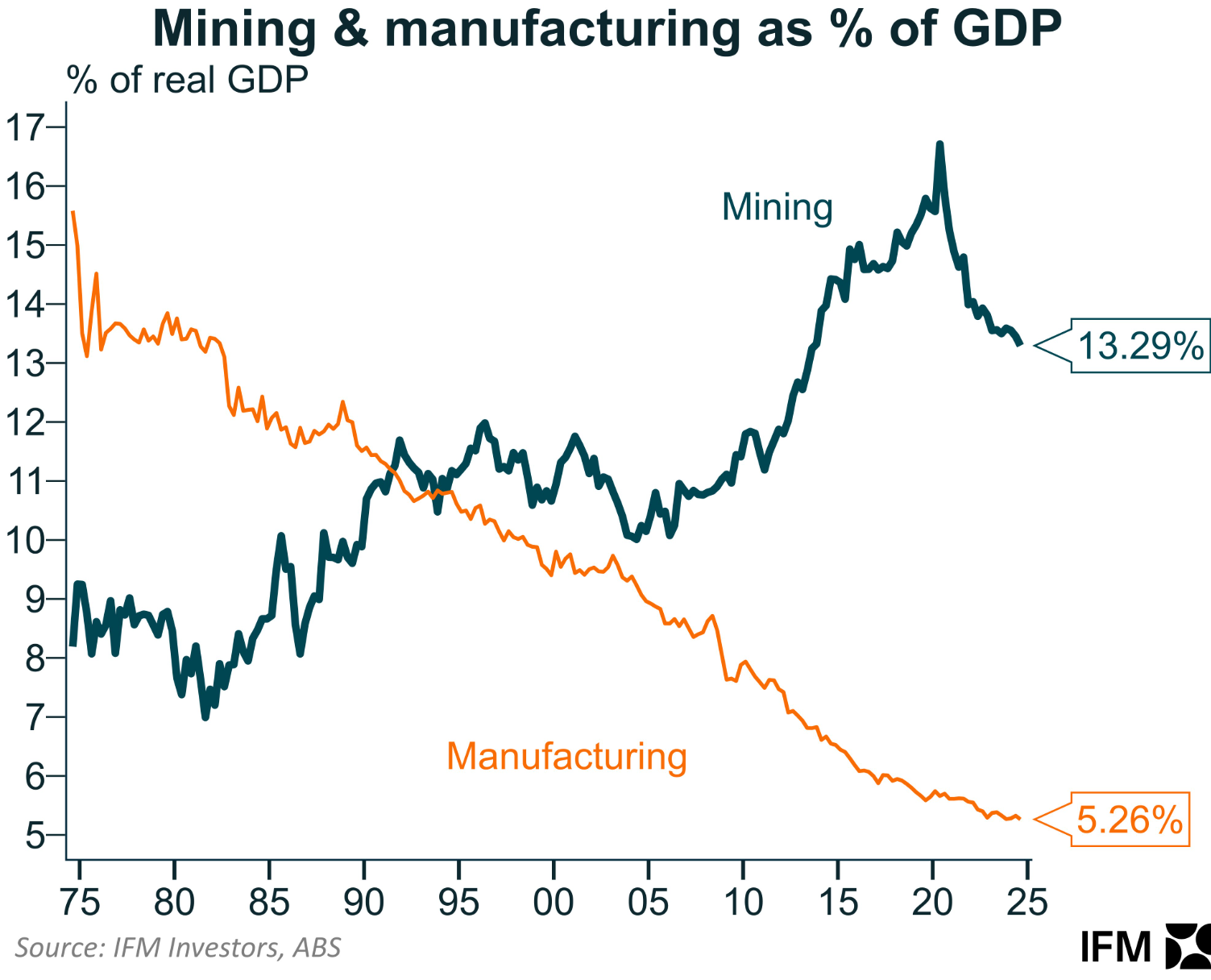

The commodity boom is certainly part of the problem. The massive rise in the Australian dollar after the mining boom kicked off contributed to the shrinking of Australia’s manufacturing sector, most visibly via the car industry.

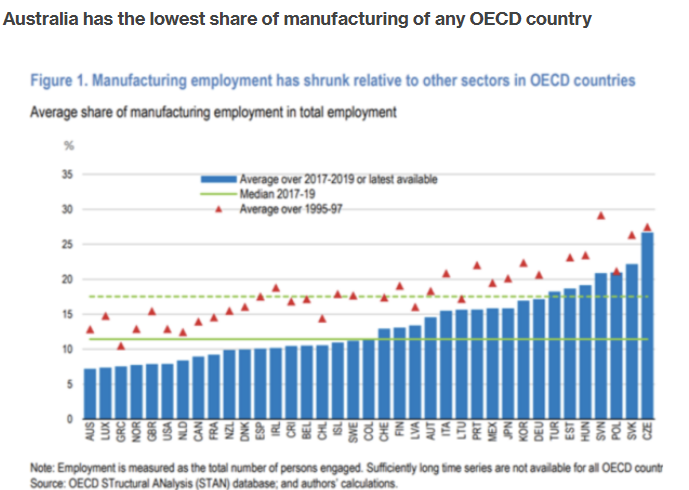

Manufacturing is subject to global competition and is dependent on capital investment and technological improvement. Therefore, it has traditionally been the sector that experiences the strongest productivity growth.

The fact that Australia’s manufacturing sector has shrunk to around 5% of GDP—the lowest share in the OECD—has helped underpin Australia’s deplorable productivity growth.

That said, there are three other factors that have also contributed to Australia’s poor labour productivity.

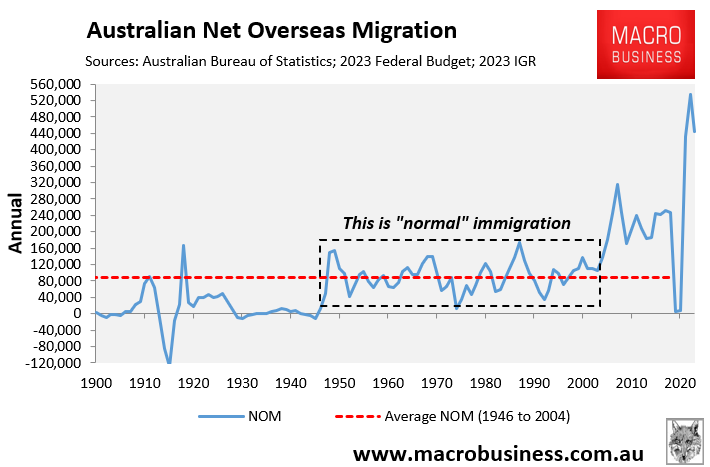

In the mid-2000s, the federal government massively increased Australia’s net overseas migration.

As a result, Australia’s population expanded much faster than business, housing, and infrastructure investment, leaving workers with less capital.

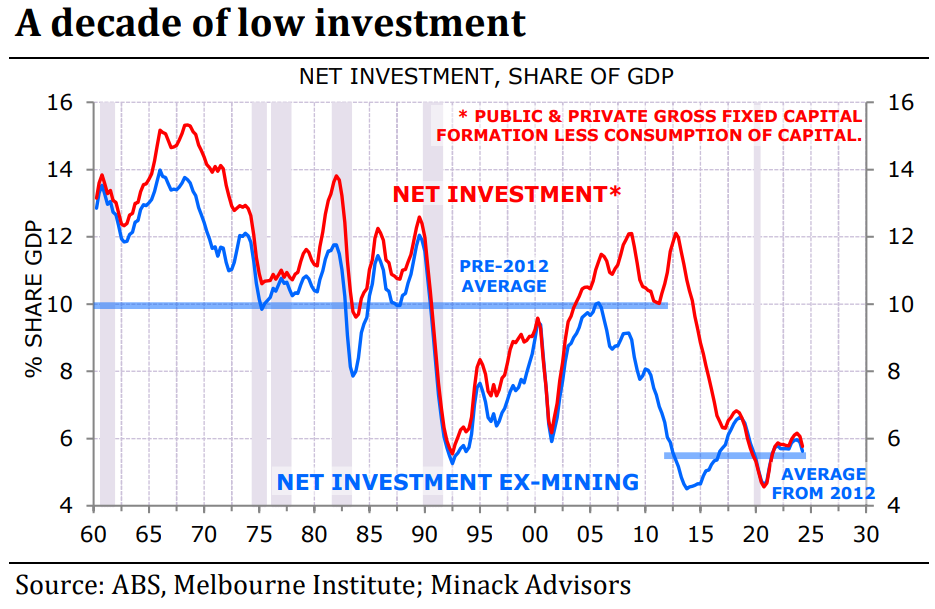

As explained recently by independent economist Gerard Minack, Australia’s “net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession”.

This “investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth”.

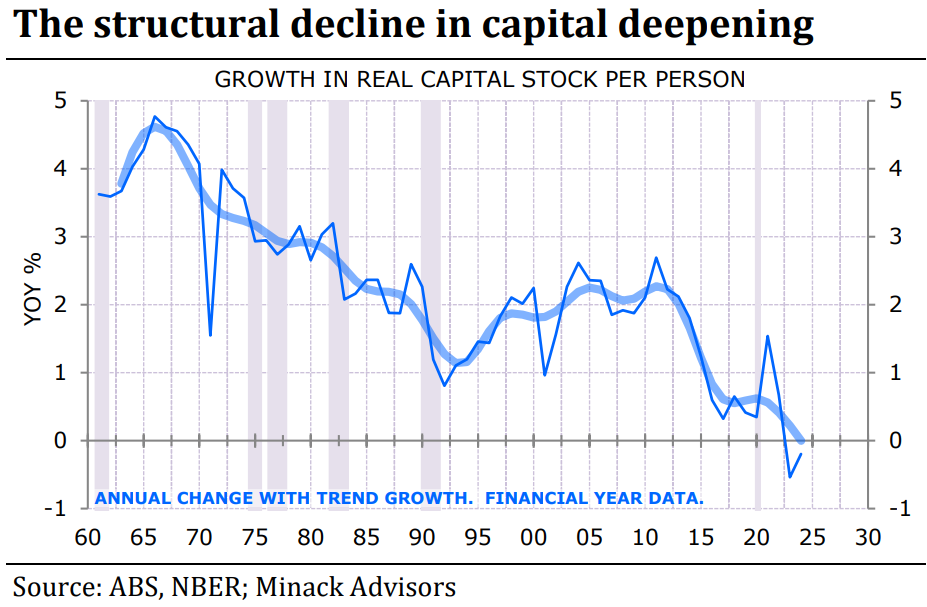

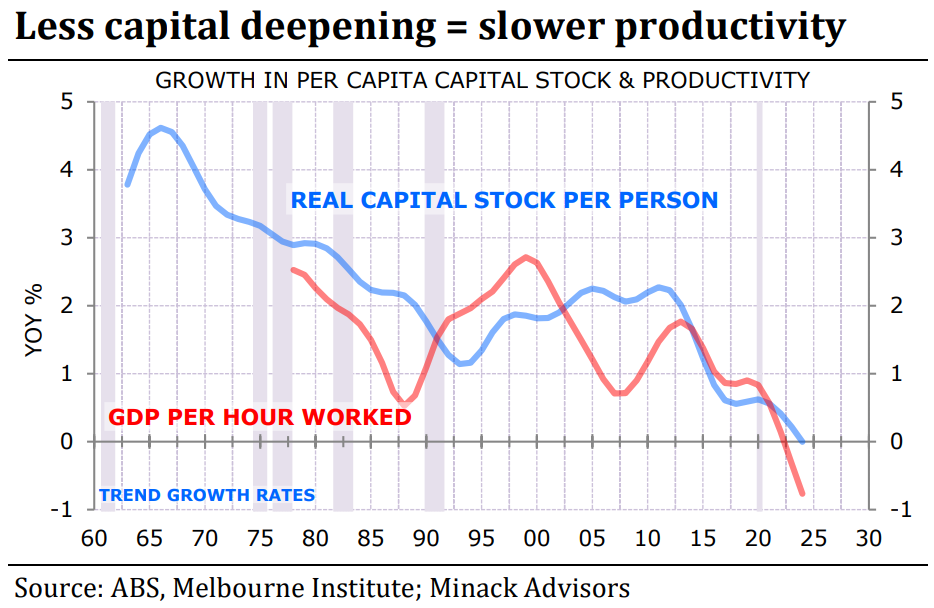

“The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”.

“Less deepening means less productivity growth”, noted Minack.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

Thus, Australia has been caught in a productivity trap because the federal government has run a permanently high migration program over business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

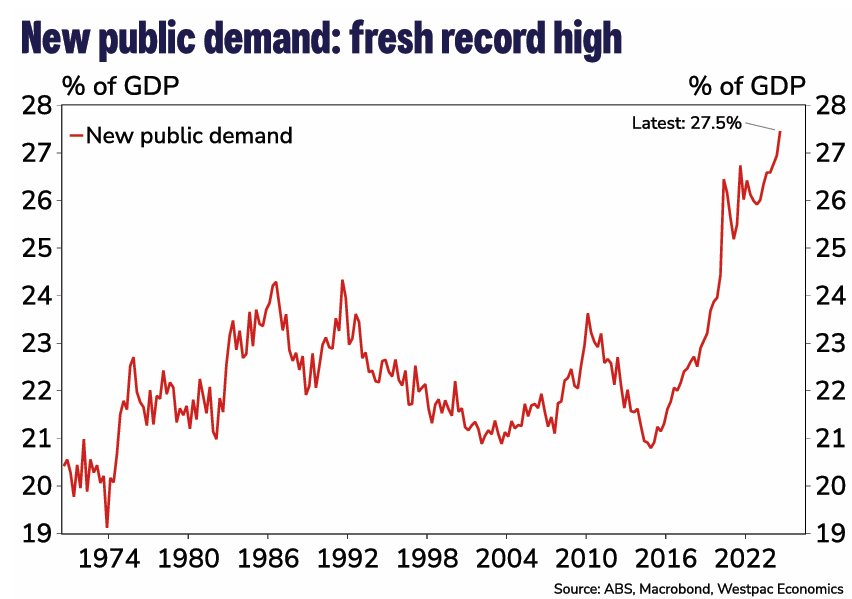

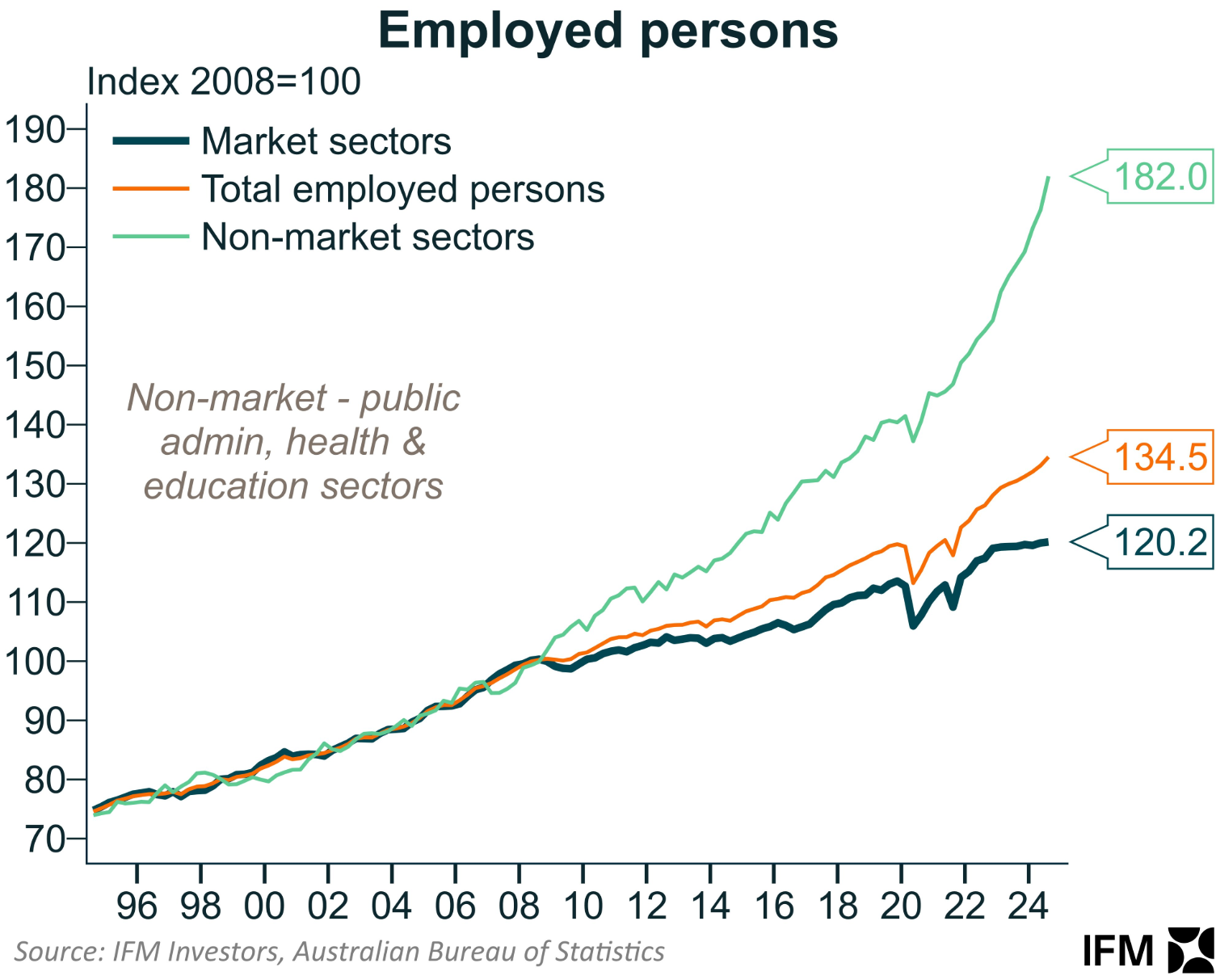

The third factor behind Australia’s productivity decline is excessive government spending, which has risen to a record 27.5% of GDP.

Much of this public spending has been channelled into low-productivity non-market (government-aligned) jobs, which have expanded at a furious pace and crowded out the market sector.

The fourth factor behind Australia’s productivity decline relates to the first: soaring energy costs.

The structural rise in Australian energy costs—gas and electricity—has contributed to shrinking the nation’s manufacturing sector, hollowing out the economy, reducing economic complexity, and eroding productivity.

The reality is that Australia can only sustain a manufacturing sector with cheap and reliable energy.

However, the failure to reserve East Coast gas supplies and the abandonment of traditional cheap and reliable baseload power have destroyed Australia’s energy advantage, despite being one of the world’s largest exporters of energy.

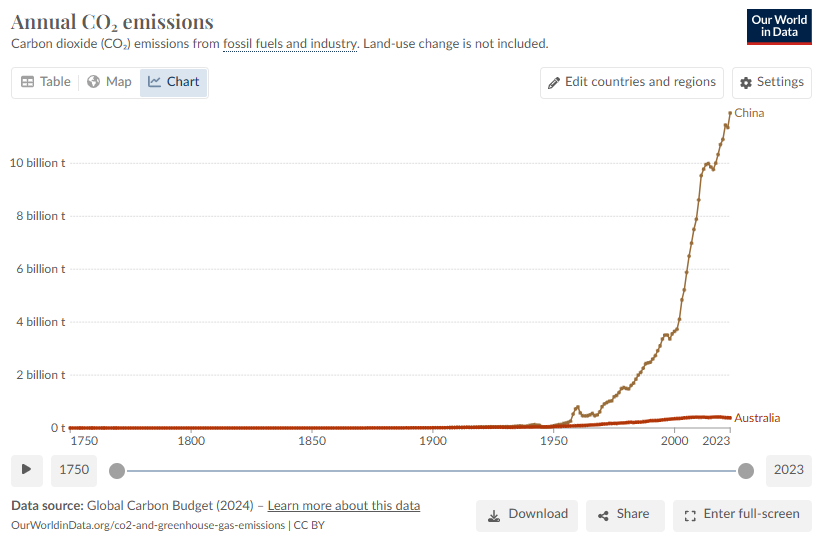

Therefore, the solution to Australia’s productivity decline must include significantly lower and more highly skilled immigration, domestic East Coast gas reservation, and the abandonment of costly “net zero” policies that drive up energy prices and merely export manufacturing capacity and emissions to China.

Australia should also pursue broad-based tax reform of the kind recommended in the Henry Tax Review to improve economy-wide efficiency.