Most studies agree that asset allocation adds way more over time than stock selection. They also agree that private investors cost themselves a lot of money over a cycle by buying after the market has risen and then selling after it has fallen.

I worry many investors spend too much time trying to second-guess their adviser. Sometimes this is justified (I’ll go into that more below), but often it is counterproductive.

The Nucleus Experience

We went to cash and close to minimum equity weights about a month ago. We still field calls from both superannuation and regular clients who are trying to second guess our allocations and reduce risk on portfolios that are already very defensive.

Here is an email we recently sent to our clients that hits most of the issues we think our investors should be aware of:

As you may be aware, there have been significant falls in share markets over the last few days on the back of COVID-19 concerns.

We have had concerned messages and calls from investors, and I wanted to give you more information.

In our tactical portfolios, we manage the asset allocation for you. About a month ago we took a very conservative stance on the back of: (a) expensive markets (b) heightened uncertainty and (c) COVID-19 flow-on effects.

We are of the view that these will last for some time and we are not yet looking to buy in.

As at the morning of 27th Feb, stock markets have fallen sharply. All of our tactical portfolios have increased in value. So far, we are on the right side of this trade. Not to say we will always get it right, but in this case, at least we believe we have positioned portfolios correctly.

Notwithstanding this, we have seen a number of clients changing from growth to income to reduce their own risk exposure (you can do this yourself on our portal).

We welcome your changes. I want you to feel that you have control over your investments both through customising your ethical constraints, your income needs and your risk tolerance.

However, I want to highlight that you may be trying to second-guess our weights and by being overly conservative, you may miss the eventual upside. Studies tend to show that many non-professional investors sell after the market falls and buy after the market rises. i.e. buy high and sell low.

I do want you to be comfortable with the risk levels in your portfolio. But, if you are scaling back your risk now, I urge you to do it because you have had a genuine and long term change in the level of risk you are willing to tolerate.

If you would like to control the risk levels in your portfolios more actively, we do have other products where you can always control the risk. These are for experienced investors who understand not only markets, but their own psychology and behavioural biases. Please contact us if you would like to discuss.

I note that you have full access to see every stock and every bond in your portfolio, their performance and why you own them. While this transparency is core to our offering, it has a downside. Not every stock we own has gone up, and so this can be concerning. We urge you to look at the overall performance – diversification means not every asset we buy will go up. In fact, some stocks are specifically held in our portfolio in case we are wrong.

More information:

We have frequently been writing and podcasting about this topic. Yesterday I appeared on ABC’s The Business talking about the risks:

We have just posted a podcast on the matter:

Here are two recent blog posts on the COVID-19 (here and here), our performance report and two prior podcasts (06/02 and 23/01).

Thanks for your continued support. Please book a call, email or join a live podcast with any further questions.

When is your concern justified?

I run portfolios top-to-bottom, so the client owns the actual stocks and the actual government bonds. This way, different managers aren’t working at cross purposes.

If you think about the experience of most superannuation or clients of financial advisers at large groups, it is very different.

I’ll use a client of a large financial planning group invested in say six equity funds across local, international and emerging markets, two bond funds and maybe a smattering of direct or alternative investments as an example:

- The four different equity managers make calls about if shares are going up or down. They are unlikely to have the same view, and so many positions will cancel each other

- The two different bond managers might have the same issue. And they might be working at cross purposes to the equity managers. Bonds are meant to provide safety to a portfolio. But maybe the bond managers are chasing returns at the riskier end of the debt market at the wrong time.

- Ditto for the alternative investment managers

- Then, often there will be asset consultants who give recommendations as to which of the above to own. They are trying to time the asset allocation and time the exposures. Switching between growth or value funds or bonds and equities. Their views will be different to the portfolio managers. Sometimes at cross purposes.

- At the financial planning group level (that employ the asset consultants), there will usually be an asset allocation committee. They will also be putting in their two cents and trying to time the asset consultants view.

- Your financial planner may or may not agree with the asset allocation committee and so (to the extent they are able to) may add additional overlays to their advice to time the committee’s investment

- Finally, the end client tries to time the financial planner’s decision as to when to invest or not

That is a lot of moving parts, each trying to second guess the next level up the chain.

If you are the end client, you have a lot of cooks in the kitchen. And you might not like the end result.

The real benefit for people in the middle of the above chain is when something goes wrong, they get to say “not my fault”. It was <insert one level higher> and I have fired them so that <insert one level lower> doesn’t have to fire me.

There is not a lot of accountability. And that is when your concern might be justified.

So, what should you do?

The first question is the most important.

Why do you have a financial adviser?

- For some people, it is the financial structuring and tax-effectiveness.

- For many, it is to organise the right insurance and estate planning.

- For others, a good financial planner is like an investment coach, talking investors off the edge when they think it is time to panic. Convincing investors not to chase the stock market higher at the end of a boom.

- Some advisers help put together share portfolios and can get access to Initial Public Offerings

- Some advisers perform the asset allocation

My key point is that there are very good planners in one category that have no idea about the others. That’s not a bad thing. But you need to make sure that what you want from an adviser is what they are capable of giving.

For example, many advisers who specialise in shares have no idea about asset allocation. They get paid to sell shares and so that is what they sell. If you are expecting them to also do your asset allocation for you, then you might be in for a shock.

Do you want to do the asset allocation yourself?

Do you trust your ability to stay calm in a crisis? Really. I’m not talking about when your barista pours a flat white when you clearly (clearly!!!) asked for a latte.

I’m talking about markets melting down, constant red on the screens, dreams of early retirement evaporating type crisis.

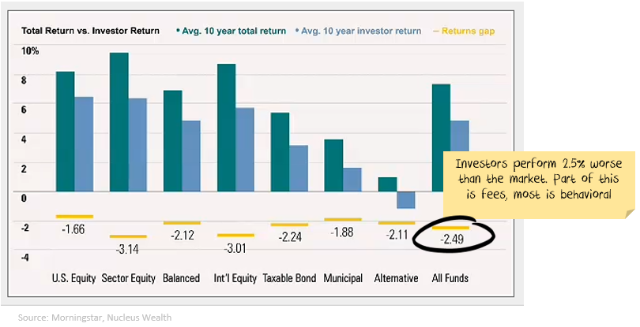

As the chart above shows, most investors don’t stay calm. It is just human nature to be swept up in the euphoria or the fear of the moment. The better financial advisors are the ones that will help you to avoid these behavioural biases.

If you want to be involved, then first make sure you have the time. And not the “I’ll watch the business report at the end of the news every night” type time. Or, “I’ll read the front-page of the business section every day and cover to cover every Saturday” type time. I’m talking about genuine time to understand the key economic issues of the day and what they will mean for your portfolio. For a start, if you don’t have time to write down why you are making your investment decisions before you make them, you probably shouldn’t be investing.

Next, make sure you have an adviser and a structure that lets you get involved to the extent that you want to be. The adviser who is excellent at your insurance or taxes may not be the adviser best suited to running a detailed investment portfolio for you.

If you are going to outsource some (or all) of your decision making to a third party, then do your due diligence at the start, work out how you want to keep track of what they are doing for you and then try to limit your meddling.

Overconfidence bias is a well known behavioural bias that we all have. For example, in a study 93% of Americans claimed to be better drivers than average, a mathematical impossibility. A similar affliction affects people’s estimation of their sexual and investing prowess.

I can’t tell you if you really are better than average at all three tasks.

But I can say of all the people that think they are, many are deluding themselves.