The buyback phantom menace

The last few weeks have confirmed our view that most of the cash from Trump tax cuts will end up as dividends or buybacks. At the same time, we are awash with articles warning of the dangers of buybacks, from Vox to the FT to the Harvard Business Review.

I’m hoping none of these arguments are intended to be smokescreens for the real issue with buybacks, but the arguments presented (buybacks take away investment dollars, buybacks manipulate share prices, buybacks encourage too much leverage) are a phantom menace, and instead divert attention from the real problem with buybacks:

Management who get paid with share options, and then use buybacks rather than pay dividends are giving themselves free money at the expense of shareholders.

To illustrate, first consider what happens when a dividend is paid:

Now compare that to a buyback:

So, let's say you are the manager (or a board member) of the above company with employee options exercisable at $16.50 in 2 years time and you are considering your choices. Which would you prefer to:

- pay 100% of profit back to shareholders as a dividend, your share price stays at $16 and your options expire worthless or

- use 100% of profit to buy back shares, your share price increases to $18+ and you make a lot of money on your options.

It is not a complicated maths problem.

And even better from a management perspective there is no accounting cost for the above gift from shareholders - its just taking a little bit of the potential share price growth from everyone which can seem like a victimless crime.

How to fix the problem

Very simple. The strike price of staff options should be adjusted for buybacks.

This removes the conflict of interest but still allows management to use buybacks to manage debt levels and return cash to shareholders.

What about Earnings Per Share growth?

Earnings per share growth is also distorted by buybacks:

So, if management gets rewarded for hitting earnings per share targets then this will give them a free kick.

The IRRC Institute surveyed directors in 2016 and had the following to say:

However, most directors said that their companies are aware of the relationship between buyback programs and compensation and that they make deliberate, informed choices to ensure that they reward executives for desired behavior rather than for financial manipulation of share prices. Anticipated buyback effects on EPS are usually factored into EPS targets, they say, and unanticipated effects can be adjusted out.

I think the above statement is wishful thinking. While some boards may be aware of the problem, I don't believe targets are being mathematically adjusted for buybacks to ensure that earnings per share isn't manipulated. Maybe, in a few cases, targets are set "a bit higher" to account for expected buybacks.

In smaller companies, directors are less likely to be aware of these problems, let alone deal with them.

I would prefer EPS targets for management to be explicitly adjusted for the effect of buybacks.

Do buybacks take away from investment or create leverage problems?

I don't think so. You can certainly cloud the argument by comparing a buyback with returns on investment and the effect on gearing and a range of other issues - and then the logic and calculations can get complicated enough to make it unclear.

But to me these are distractions. In my view most companies start with free cashflow1 and then go through the following investing/financing decisions relatively independently:

- How much expansionary or growth capital expenditure would the company like to invest (i.e. capital expenditure to expand the business)

- Should the business have more or less debt

- How much capital should be returned to shareholders

The first decision (investment) is usually independent of the second two decisions in most large companies. Investments are judged vs some sort of hurdle (e.g. projects should generate a return above x%). With corporate debt yields close to record lows, and the world awash with capital I find it unlikely that worthwhile investment is not being made due to lack of capital. The Harvard Business Review has one of the better analyses of the issue.

The next two decisions are interlinked in so far as the whole system needs to balance. For some companies, the board will decide how much capital to return to shareholders and the balance will go to increasing/decreasing net debt. For other companies, the board will target a debt level and the remaining cash will be returned to shareholders.

Either way, for capital returned to shareholders the decision process is in this order:

- decide how much capital to return to shareholders

- decide whether the capital be returned be via a dividend or a buyback

Comparing buybacks to debt levels or capex is not meaningful in my view as the decisions are made separately.

A more likely culprit for the increase in borrowing is the low corporate borrowing rates making debt more attractive. A more likely culprit for the low level of investment is the lack of demand and depressed levels of capacity utilisation. i.e. companies are borrowing more because it is cheap to borrow, companies aren't investing because they still have spare capacity.

Do buybacks have trading problems?

Maybe. A company buying back stock after a bad announcement can be looked at as manipulation to keep the price high - especially if management has share options expiring or margin loans. But, it can also be looked at as providing liquidity in times of stress or as an opportunistic purchase by management at a lower share price.

If you were a regulator cleaning up buyback regulation, completely removing the company from any trading decisions or having them pre-committing the amount of trading may be worth considering to avoid manipulation.

Do management make bad investment decisions?

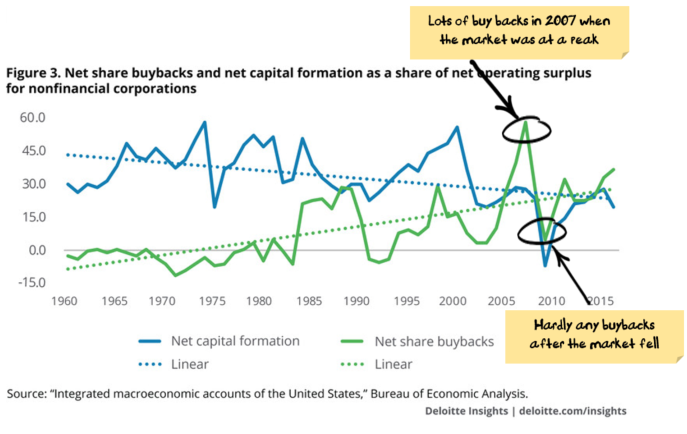

At face value, yes:

Even Costco with renowned value investor Charlie Munger on the board was busy buying stock in 2007 at the peak and by 2009 it had almost no buyback.

But this is again the wrong question to ask.

If you take the view that the first decision is "how much capital to return to shareholders?" and then the second decision is "should it be via a dividend or a buyback?", it makes sense that companies had lots of capital to return in 2007 (when profits were high) and then didn't have capital in 2009. i.e. in 2009 the answer to the first question was "not much" and then the answer to the second was "try not to cut the dividend", which left almost no money for buybacks.

Another valuation issue to note is that the table at the top of this post is not sensitive2 to the valuation of the company - if the stock maintains its price / earnings ratio then it is no better or worse for investors if the example is done on 30x price/earnings or 5x price to earnings:

So, if the valuation doesn't change (or the earnings multiple stays the same) then there is no difference to shareholders from a buyback or dividends.

When the earnings multiple goes up, investors would prefer that management had been doing buybacks (as it "forced" the investor to own more stock by the company keeping the cash), and vice versa.

But this is hard to pin on management when it doesn't work - you are the investor. If you own too much of an expensive stock that is buying back shares then the onus on you to sell some of your stock, if you own a cheap stock that is paying dividends then reinvest the dividends yourself.

In either case, you shouldn't be hoping that management will make your investment decisions for you.

Are there any other issues that are relevant?

Most countries tax capital gains more lightly than dividends, and tax on dividends needs to be paid every year whereas tax on capital gains only needs to be paid upon the sale of shares. This means that for most investors a buyback will deliver a better after-tax return than a dividend.

Stockbrokers (and their corporate advice departments) don't get paid when companies pay dividends. They do when companies buy back shares. So, the advice that companies get from brokers is unlikely to be balanced.

It is possible that buybacks increase the value of the stock relative to its earnings through increased demand. i.e. the price/earnings ratio of the stock is higher. If this is the case (it probably is in the short term) then it makes buybacks even more attractive for both investors and management.

Final recommendations

For regulators: The strike prices of employee options should be adjusted for buybacks - you are probably the only hope for shareholders because both boards and management are in on the scam.

For investors: ask the companies you invest in why the strike prices of employee options aren't adjusted for buybacks, try to have management earnings targets adjusted for buybacks. When you are looking at EPS growth to compare companies, you may need to adjust for buybacks in some cases.

For managers: Keep buying back shares rather than paying dividends if you have options or earnings per share targets. Hope that investors and regulators don't catch on.

For boards: Keep buying back shares rather than paying dividends if you have options. If you are on a board and have options, you may be regretting reading this post. You are legally meant to be looking after shareholders and so now that you know, you should probably do something about it. Make sure any management earnings targets are adjusted for buybacks.

Footnotes

1. Free cashflow = Cash from operations less replacement or required capital expenditure (i.e. capital replacing existing plant & equipment or capital needed to keep the business operating at current levels).

2. This is close to true. For the pedantic, it matters what share price the new shares are bought at, but we are usually talking differences in returns of less than 0.1% . For the really pedantic, over time the investor getting dividends (and presumably not re-investing them) will have a lower exposure to the company and so will be less affected by falls in price if the expensive company becomes less expensive. This investor will also miss the upside if a cheap company becomes less cheap. While we are being pedantic, if the buyback meant that gearing gets too high then that would affect valuation as well.

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at Nucleus Wealth.

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen is an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management, a Corporate Authorised Representative of Integrity Private Wealth Pty Ltd, AFSL 436298.