Last year, I was wrong about NVIDIA. NVIDIA, in many ways, got “lucky” with crytpo revenue in the early 2020s. NVIDIA happened to have a chip that was efficient at mining, and revenue boomed, then busted. I think that coloured my view on the artificial intelligence market. However, NVIDIA has changed the conversation. While I still think NVIDIA is a lucky beneficiary of the artificial intelligence boom, it is developing a compelling case for a paradigm shift in computing.

This is a three-part series looking at NVIDIA and artificial intelligence (AI) – how big is the opportunity, can it save stock markets from interest rate hikes, and how can/should you get exposure?

Part 1: Is NVIDIA the Cisco kid?

- Parallels with Cisco: consider similarities with NVIDIA and the lessons from history.

- NVIDIA position: Have a look at NVIDIA and its own history; what is different about it; where does it fit in the market?

Part 2: How big is the AI market

- Market potential: Look at the artificial intelligence market. How big can the processing part of it be?

- Options: Look at what options investors have

Part 3: NVIDIA: what if it is not just about AI

- A new paradigm: Maybe NVIDIA is not just an AI stock…

- Investment: What are the investment parameters

Part 1: Is NVIDIA the Cisco kid

And I’m not talking about NVIDIA being a wild west vigilante. I’m talking about NVIDIA playing the role Cisco played during the tech boom.

A quick background

NVIDIA has now topped USD 2.5 trillion in market value. NVIDIA’s stock is now worth more than Amazon and Tesla combined, and short sellers have lost billions.

NVIDIA is riding the surge in interest in artificial intelligence following the ChatGPT release in late 2022.

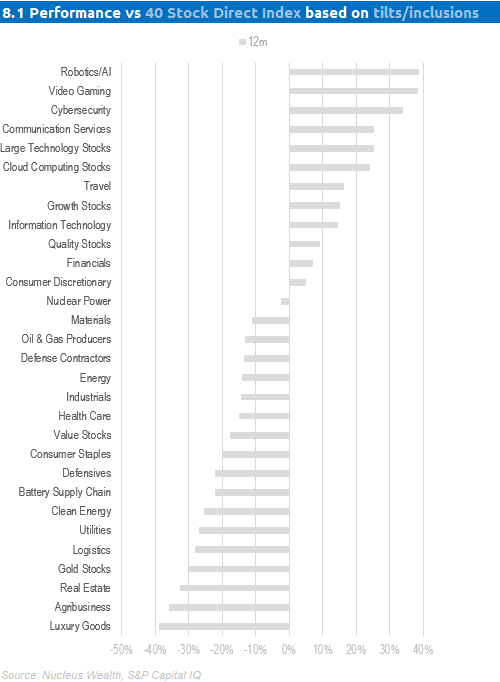

Direct Indexing investors who chose the “Artificial Intelligence” tilt are celebrating…

What sparked the share price rally is a crazy increase in expected sales to Data Centers. NVIDIA sales have been doubling every 3-6 months. If NVIDIA can repeat that trick a few times, then you won’t care that the current share price looks a little expensive. The big question: can it?

a. Parallels with Cisco

Cisco provides networking hardware. In the early days of the tech boom, Cisco was looked upon as a seller of “picks and shovels” to the internet boom. Better still, Cisco had technological leadership, a reputation for quality and was expected to continue to be a long-term winner.

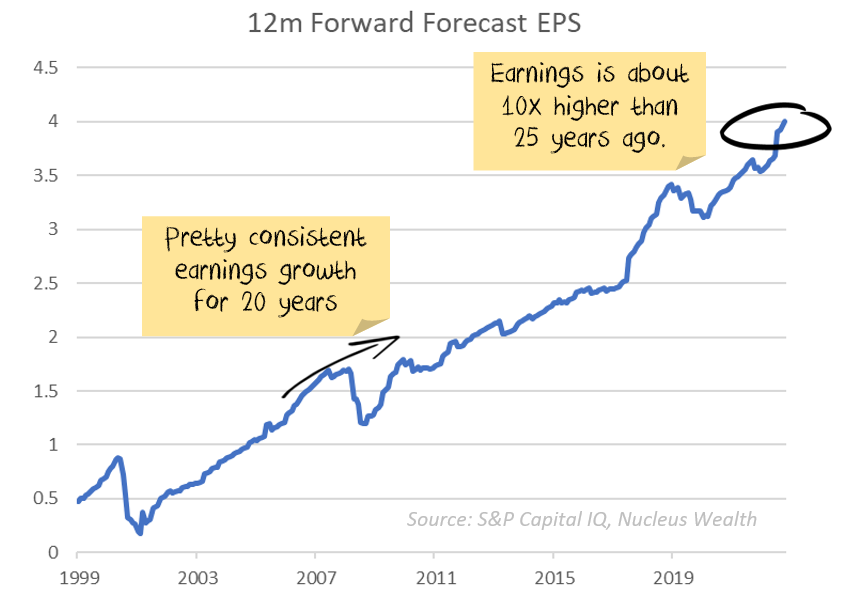

From an earnings point of view, Cisco was a winner. Earnings per share is about ten times higher in 2023 than in 2000:

Technologically, Cisco has maintained leadership.

The problem? If you bought during the tech boom, you are still down about a third on your purchase:

The most important lesson, as always, is price matters.

The other lesson: if you are selling “picks and shovels”, you can’t expect to capture an unrealistically high proportion of the gains. Your company exists to enable the new technology, not to hold it to ransom.

NVIDIA/Cisco parallels

NVIDIA looks to have many of the same characteristics as Cisco. Both have leadership in a critical component. The internet can’t exist without networking equipment. Artificial intelligence requires computing power.

The tech leadership from both companies is incredibly useful to customers, but not irreplaceable. Other routers may have been less advanced/reliable than Cisco’s, but they were usable. NVIDIA chips are considerably more efficient than alternatives, but there are alternatives.

There is a but. And it is big. NVIDIA might not be just about selling GPUs

2. NVIDIA Positioning

NVIDIA started providing graphics chips for computer games. It remains the leader in dedicated graphics processing units, with an 85% market share. Having said that, if you include integrated units, NVIDIA falls to 2nd or 3rd. Intel dominates the overall count, with between 60 and 75% market share, then NVIDIA and AMD.

The benefit of graphics chips is that the calculations needed for realistic gaming video are very similar to those required for artificial intelligence.

They are also similar to the calculations required for cryptocurrency mining, which explains the boom in NVIDIA’s share price in 2022.

The crypto angle is complicated.

Over the early 2020s, NVIDIA sales were dominated by sales to cryptocurrency miners. But not bitcoin miners. Bitcoin mining is more efficient on ASIC chips. NVIDIA chips are (probably) seldom used for Bitcoin.

Other crypto miners love NVIDIA chips, though. In particular, the second largest cryptocurrency, Ethereum, was (past tense) efficiently mined using NVIDIA chips. Which was great for a few years, despite NVIDIA trying to limit crypto use. How great? It is tough to tell. We can only guess at what proportion of chips were being used for mining. But probably close to half. Potentially more.

What put a huge spoke in that wheel was in late 2022 when Ethereum moved from proof of work to proof of stake. This decreased the power needed by more than 99%. And the demand for mining with it. NVIDIA’s “gaming” revenue, which is where most of the crypto sales probably resided fell by more than 50%.

Now, some of this fall is likely a flood of second-hand units from suddenly idle Ethereum miners. Other (much smaller) coins can still be mined using NVIDIA units.

Net effect: a billion (or two) per year in sales to crypto miners are probably still in NVIDIA’s numbers. The downside risk is that these disappear over time. The upside risk is that a crypto coin somewhere that needs lots of NVIDIA processing becomes the crypto du jour. The worst of the downside is probably behind us.

China is transitioning from a customer to a competitor.

China is the second largest market for artificial intelligence. The US has banned high-end NVIDIA chips from being sold to China.

China is going to try to create competitors to NVIDIA. I suspect the competitors will come sooner rather than later. China will not be particularly successful. But, China is more likely to spend its money on developing its own chips rather than buying 3rd generation NVIDIA chips.

China will be a minor drag on earnings. There are some future competitive risks. But they are a long way away.

Scalability is a two-edged advantage.

It is very impressive for any manufacturing company to double production every few months in what is its biggest division. Especially when you consider the work that goes into building a semiconductor factory and sourcing the components and staff.

The reason that NVIDIA can expand so quickly is that NVIDIA doesn’t actually manufacture the chips. TSMC and similar contract manufacturers do the actual work.

A doubling of NVIDIA’s production would be significant for these companies. But it would be a much smaller proportional increase. And given the weakness in semiconductors recently, it is likely a simple rediversion of existing capacity.

Which shows the benefit of outsourced manufacturing.

But it also highlights that NVIDIA has design leadership, not vertically integrated leadership.

Say a competitor strikes on a better chip design. Someone like TSMC would have the capability and expertise to really quickly build the chip. And just as importantly, scale production. This is not a base case scenario, but it shows that NVIDIA’s “economic moat” is not as wide as the moat from the vertically integrated chip makers of 20 years ago.

It is a “busy” competitive space.

Google, Amazon and Apple all have artificial intelligence chips. AMD have a foothold. Intel is not really on the board yet but has graphics processing units and a large research & development budget. Microsoft is involved at both ends of the value stack, with cloud computing and artificial intelligence models.

Google and Amazon do already use NVIDIA chips, but they may start using their own chips if they can reach a certain level. Microsoft is more complementary, strong where NVIDIA is weak and vice versa.

NVIDIA is clearly in the best position. It has an entire ecosystem of software tools and networking to enable customers. And no signs of losing that leadership. But NVIDIA also has deep-pocketed competitors and the most to lose.

Datacenters are not the best client for profit margins

The increase in sales is to datacentres. Unfortunately, they are a very price-sensitive customer.

To contrast, say I’m a 20-something man-child putting together a gaming rig in my parent’s basement. I might be spending five grand. Can you convince me to get the latest video card for $2,000 rather than $500? Sure. Maybe the $2,000 card is only 25% better, but I might pay the premium.

Data centres are different. If your card is 25% better, but costs 3x the price, maybe the data centre will just buy three cards at $500 rather than one at $1,500 and have more processing power.

The next year or two might be the exception to that statement as there is a scramble to offer artificial intelligence capabilities.

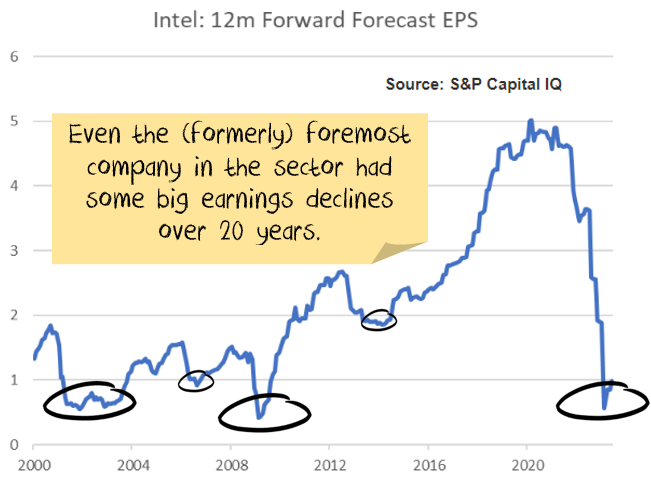

Semiconductors are a cyclical industry with high research and development requirements.

The sector is very cyclical. We have seen four big downturns over a 20-year period, with many smaller ups and downs:

Intel has been the sector leader for most of the last 25 years. But earnings have been volatile over that time. 50%+ falls in profits have happened on multiple occasions.

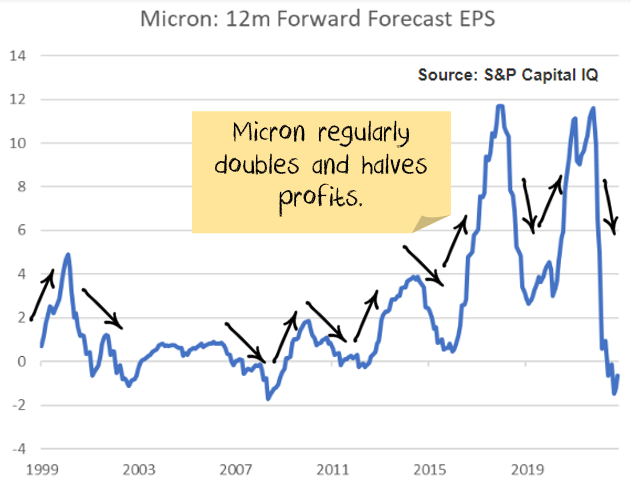

And Intel has been a steadier performer than many in the sector. Micron does memory chips, one of essentially three companies in the sector. It is a big company, USD75b market cap. The volatility of earnings are crazy:

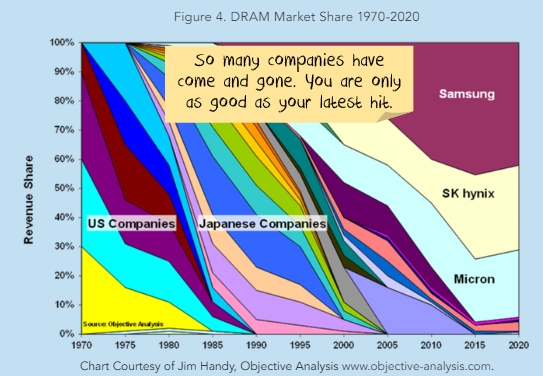

The lesson is that market leadership is good, but ephemeral in the semiconductor space. A car company might be able to live off reputation for decades. In the semiconductor space you can measure how long you live off reputation in quarters, possibly months.

NVIDIA is a great company with market leadership and a huge market share. It has been early into data centers and AI, establishing a leading position. However, the industry is highly cyclical and companies can lose leadership quickly. This is evident in NVIDIA’s own profits, which have had big swings in the past year.

Semiconductor valuations are complicated.

Given the complexities that you see and the volatile earnings, market leaders in each segment do not tend to be expensive. Think 10-15x earnings. Sure, smaller companies who are picking up market share rapidly and growing can be a lot more expensive.

But in a steadyish state, given the market structure problems above, semiconductor companies tend to trade on a (well-deserved) discount to market prices.

Next, valuations can give incorrect signals. Say we think a semiconductor company will earn $10 a share over the cycle, but that will vary between $1 and $20. We decide to pay 14x the average $10 for it, i.e. $140 per share. The problem is that earnings are volatile:

- In the boom year, we pay $140 for $20 of earnings, putting it on a P/E of 7x. So, it looks cheapest at the top of the cycle.

- In the bust year, we pay $140 for $1 of earnings, we are paying 140x P/E. Which means it looks most expensive at the bottom of the cycle.

- And history says we are often better buying when it earns $1 and selling when it earns $20. Which means buying, confusingly, when it is “appears” expensive and selling when it “appears” cheap.

Part 2: How big is the market?

This is a quick primer on the AI market. How big is it and how can/should you get exposure?

a. Market potential: How big is the opportunity

There are three ways to get to numbers for this. First, you can start with NVIDIA’s current numbers and try to forecast growth. When companies are growing quickly, this is next to impossible. A small change in assumptions can make an extraordinary difference in the outcome.

The second way is to look at the total market size and then make assumptions about the possible market share.

Private investment in artificial intelligence

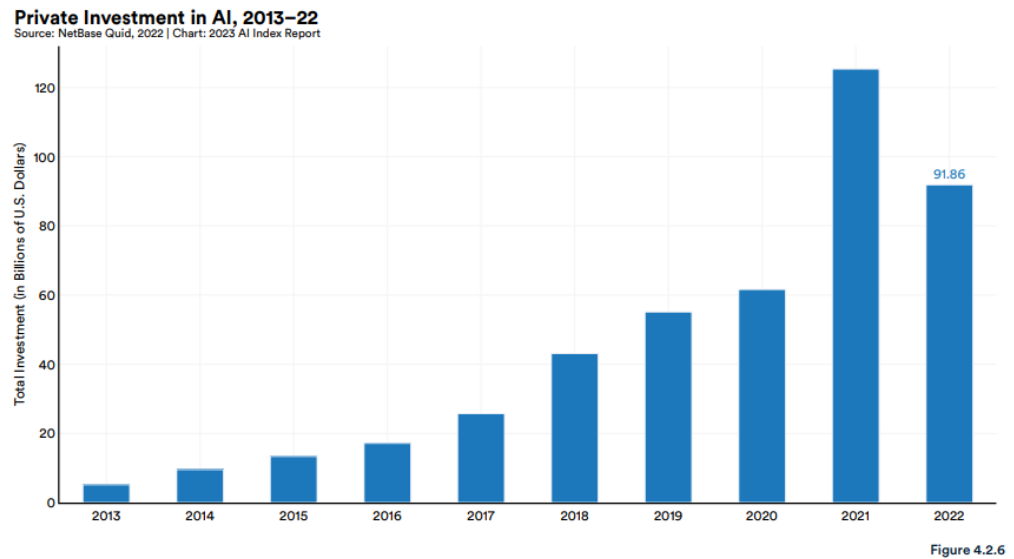

I’m using NetBase data for this:

It is hard to know how accurate this data is. It seems credible, but my guess is that there are going to be lots of job title changes to make it sound like there is some involvement in artificial intelligence. So, some of this is going to be bullshit. I stop calling my offsider an analyst and start calling them a data scientist. I rename a statistician to a machine learning specialist. They get a salary bump, and I get to tell my shareholders what a good job we are doing. But! There is going to be a lot more bullshit since the launch of ChatGPT.

Secondly, the NetBase data fell by 30% in 2022. It is hard to tell why. I suspect the best explanation is that there were a lot of SPACs and venture capitalists raising money in 2021. And then that disappeared into 2022. If NVIDIA is any guide, some of this money will be back in 2023.

Then we need to take out any spending by China. Chinese companies are banned from using the most advanced US technology and so for listed companies are unlikely to be a significant source of sales going forward. If we average 20221/22, take out China then we are starting with a market size of about $100 billion. Lets be aggressive. Say this can go to $400b in short order.

So we are talking about an extra $300b in spending on artificial intelligence.

Keep in mind also that AI is very compute intensive up front, but apply the model is simpler. It is similiar to a regression. The hard work is creating the formula, say y = 1.3 + 2.1x. Once we have the formula though, calculating y from a given x is easier. Having said that, you will apply the model exponentially more than you create the model.

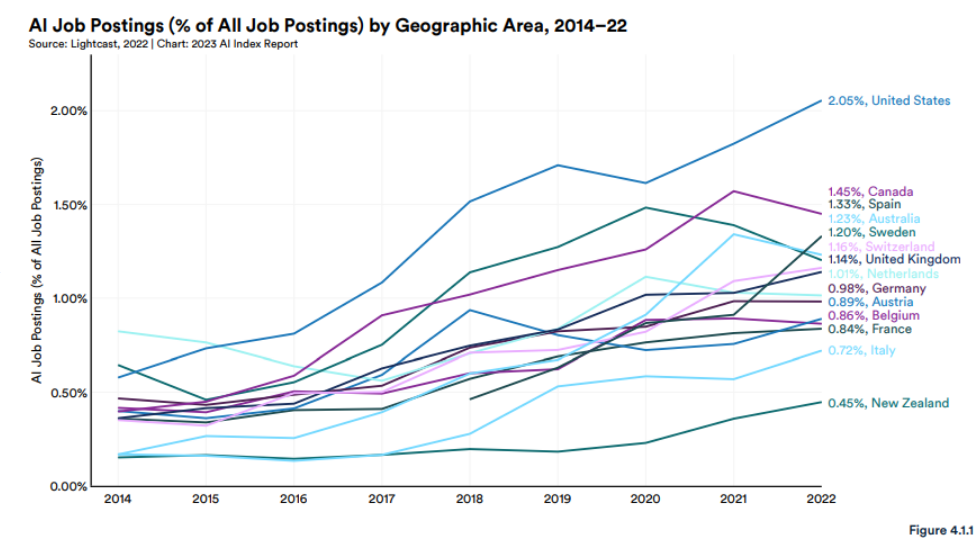

The issue I have is that most of the money is going to go on staff. My estimate is that you will probably spend around 70-90% of money on salaries and other expenses, vs 10-30% on running tests. This same report suggest already that 2% of job ads in the US are for roles that could involve AI:

Sometimes this will be the wrong assumption. If you need to ingest the entire internet for your model, then you will need to spend tens of millions. On the other hand, Goldman Sachs just patented an AI model to interpret whether communications from the Federal Reserve are hawkish or dovish. That is a limited dataset. You are probably running that analysis on your own laptop. i.e. spending $0 on (additional) computing power.

So, of the extra $300b, we are talking say $75b on computing costs. But that isn’t all going to NVIDIA. Deduct the profit margin of data centres, memory, storage, power, data centres, infrastructure staff and equipment. A heroically optimistic assumption would be that NVIDIA end up with 30% or $25b.

Which is not that far off the increases NVIDIA already announced. So maybe this estimate is low.

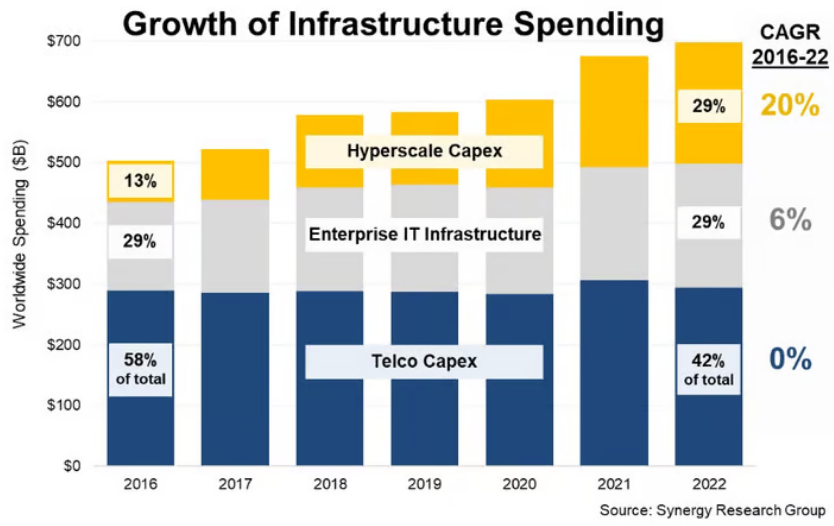

Data centre capex

The other way to attack the market size is to look existing spend at data centres and scale up from there.

The latest 2024 first quarter numbers suggest that the Hyperscale capex (the yellow in the chart above) is now running at $300b rather than $200b.

I’m assuming the enterprise IT and telco capex aren’t going to be meaningfully affected. This is mostly about compute, not data transmission.

This means we start with $300b on Hyperscale capex per year. Again let us be really, really aggressive. Say capital expenditure goes to $500 billion in short order.

Of this spend, 50-60% goes to data centres. Say $175 billion.

Data centres make 30%+ margins. And I’m guessing if there was a doubling of demand the margins would be higher. Ignore that though, say we still have $125 billion to spend.

Of that spend, 55-60% goes on servers, and the rest on power, networking, staff, infrastructure, rent etc. So, $75 billion to spend on servers.

How much of a server cost ends up with the processor? It varies depending on the use case. But, if you are buying state-of-the-art processors to speed up your calculation, you can’t skimp on storage, power, networking, memory etc. If you get a low-end but relatively beefy server around $10,000, then 20-30% might go to the processor. At the high end, a $300,000 supercomputer might see 80% going to the processor.

So, how big is the market?

The real assumption is what type of artificial intelligence people want to run:

- If it is about running models over large but finite datasets. For example, financial data, health datasets like DNA, or engineering results. Then we are more likely to end up with lots of cheaper hardware, and NVIDIA maybe adds another $10-15 billion in sales. That would mean profits around $25 billion in a few years. Which is well below what analysts are currently predicting.

- If lots of companies want to ingest datasets the size of the internet, then NVIDIA could be closer to $40 or $50 billion in profit. This is marginally below current forecasts.

b. Investment

If I knew for sure that NVIDIA would:

- end up with a $50 billion dollar profit in a few years

- grow from there at normal semiconductor rates

- have normal semiconductor earnings/margin volatility

- have 90% of the artificial intelligence processor market

Then I would maybe pay a market multiple. Maybe. More likely I would want a small discount, similar to other semiconductor stocks. Which is probably 30% lower than the stock currently trades.

So, either NVIDIA is in a bubble, or there is something else driving NVIDIA.

What are your artificial intelligence investment options?

Lots. Let me start with a framework. Artificial intelligence is a productivity tool, and the latest advances open up uses to a significantly larger range of people. It is analogous to the introduction of the internet or the personal computer in making people more efficient.

Four groups can benefit from the productivity changes, and the amount of benefit will vary by industry:

- AI companies: Can charge for the product and make returns.

- Profit margins: Companies can use productivity gains to widen profit margins.

- Wages: More productive individuals can demand higher wages.

- Prices: End consumers can benefit from lower prices for end products.

Non-AI company investment options

My contention is that AI will create a multi-year productivity boom, even in many companies not directly exposed to AI.

In competitive industries, say car manufacturing or building materials, the gains will primarily be competed away by lower prices.

More niche industries with higher value employees, say doctors or lawyers, will likely end up in higher wages for senior staff as they need less support.

Companies with high barriers to entry or oligopolistic features will end up with higher margins.

In this video I go through the winners and losers in a lot more detail:

Summary types of stocks benefitting from AI:

-

- Quality stocks. Monopolies. Oligopolies.

- Healthcare / high-service cost businesses

- Defence contractors

- Interest rate sensitive

Summary types of stocks suffering from AI:

-

- Value stocks

- Intermediaries

- Broadly competitive industries

- Disruptable industries

AI company investment options

Keep in mind for most of the companies below, AI is a subset of what they do, not the main game. Yet.

There are effectively four layers to consider:

Software providers:

These companies produce the software that others will use. I suspect these will end up a bit like browsers on the internet, largely free to consumers. Effectively paid for from advertising or lock-in to cloud services. Likely to be some (expensive) high-end models provided to big companies for private use.

The only real players currently are Alphabet (Google) and OpenAI (unlisted, partly owned by Microsoft). There are hundreds of companies trying to sell add-ons or alternative products.

Cloud Infrastructure:

The infrastructure needed to run the advanced models is quite specialised. It makes sense to rent the equipment rather than buy your own in most cases. Which means lots more money spent on cloud computing providers.

The big players are Alphabet (Google), Amazon and Microsoft.

For Nucleus Wealth clients – choose a Cloud Computing as a “tilt” to your portfolio to get an additional weight to a basket of these stocks:

Processing:

The hardware, software and networking to run AI models. This is where NVIDIA dominates. It operates across all elements, as does Google. Amazon is having a go at the hardware, likewise AMD. In the system and networking, Broadcom shouldn’t be overlooked. In the software (supplying libraries that AI models will use), Google, NVIDIA and OpenAI are the main players.

For Nucleus Wealth clients – choose large technology stocks as a “tilt” to your portfolio to get an additional weight to a basket of these stocks:

Then there are the indirect beneficiaries. TSMC and GlobalFoundries are the obvious winners, as is ASML, who supply high-end equipment that makes the equipment. The memory chip companies, Micron, SK Hynix, Samsung will likely benefit. More so if there are lots of lower-end machines sold rather than a small number of supercomputers.

Consultants:

Not really a major thing just yet. But it is coming. IBM, Accenture, Cognizant, Capgemini and others will gladly take the money of those who are late to the party and need to put “AI” in their next annual report or press release.

How to invest

Will there be a bubble in AI stocks? At the moment, the answer looks to be yes. But who knows with these things. If you want to try and ride the hype, finding the smaller stocks will be key. For most of the other large technology stocks, AI is only a small part of a large business.

There are a lot of smaller companies heavily involved in AI, or if you are so inclined you can trawl through the suppliers to companies like NVIDIA to work out which ones will benefit.

Within our active portfolios, we have lots of exposure to cloud computing, and a reasonable exposure to semiconductors. The consultants are on my radar.

For anyone using direct indexing, if you want extra (broad-based) exposure to these stocks, choose AI as a tilt to your portfolio:

Part 3: It is not just about AI

NVIDIA has started to make a compelling case for a paradigm shift.

The big picture comparison here is that data processing speeds keep halving, commonly known as Moore’s law. The single CPU version of this has been tailing off in recent years as the limits of physics and miniaturisation are being reached. There may be a quantum computing solution at some stage, but certainly not imminently.

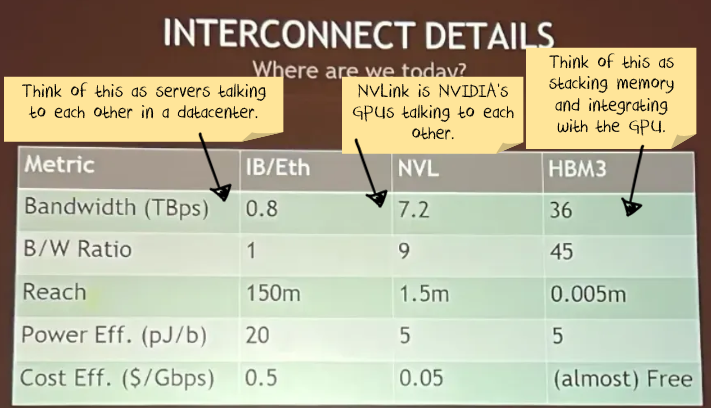

However, the reality is that you don’t care whether your computer / phone / device uses one chip or not. You just care whether the data is processed. And this is where NVIDIA is stepping in with the view that future computing is about two things:

- How to make GPUs talk to the other components of a server (mainly memory) more efficiently

- How to make the chips (mainly GPUs) talk to each other more efficiently

- How to make groups of chips (analogous to servers) talk to each other more efficiently

i.e. it is a re-framing of Moore’s law. The individual chips might only be getting a little better each year, but if the data center as a whole is getting much better every year then the effect is the same.

Why this matters more now, is that artificial intelligence requires far more data than what can be expected to fit on single a chip or a single server. And so if NVIDIA can be the master of:

- the GPU chip

- getting GPU chips to talk to each other

- getting groups of GPU chips to talk to other groups of GPU chips

… then maybe we are going to go through another paradigm shift in computing and where the value is.

Semiconductors background

The semiconductor market is a nasty industry. Companies come and go all the time, you have to keep spending on R&D, innovating and building new factories. Take the memory market:

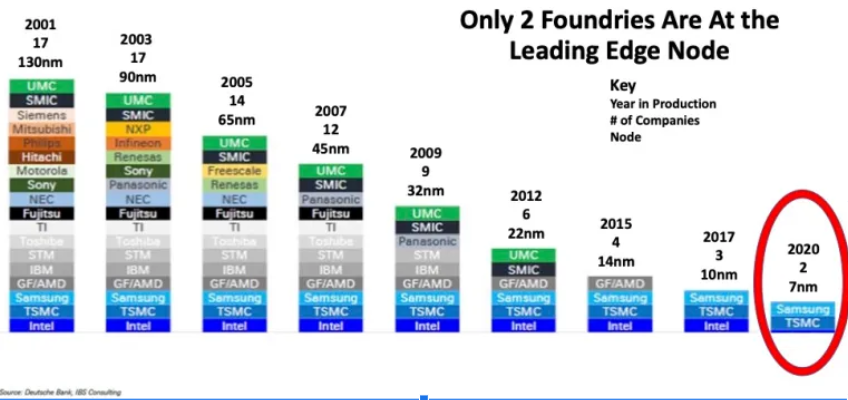

Or if you look at leading-edge foundries:

IBM was the king until it was not. Ditto Intel. Texas Instruments. The list of the once mighty is long.

Generally, it seems to be a technology path taken by a new player that everyone else thinks is not worth exploring.

Then, once the new company has a technological break-through, it is then about exploiting that into dominance. This is the path that Intel followed with its PC chips (until it became an also-ran). Or, ASML making a bet on Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography. Or TSMC taking all of the low value, high volume work away from US companies only to work their way up the value chain.

There is also a long list of companies with technological break-throughs that never made it to the dominance stage. Which will NVIDIA be? And can it take an advantage in GPUs and leverage it into a broader opportunity?

What is the opportunity?

This is NVIDIA’s key chart:

So, if you can do more calculations on each GPU and you can communicate between GPUs more efficiently, then you save heaps on power, and the speeds are way faster.

The trillion dollar question: Are we about to undergo a fundamental computing shift where this model becomes the future of data centers?

Hit me up in the comments with your thoughts – if you genuinely know something about this area!

NVIDIA’s ptich seems compelling.

If NVIDIA’s vision is the future, NVIDIA profits can keep growing for some time and NVIDIA may well become the largest company in the world. If there is an alternative technology that will trump this, or a reason that this trend will reverse then NVIDIA is looking expensive.