Last week, the Morrison Government announced that it would allow cash strapped Australians that have lost their jobs to access up to $20,000 in savings from their superannuation fund.

It is anticipated that the measure will lead to withdrawals of between $27 billion to $60 billion, which has prompted calls from industry superannuation funds for a ‘liquidity backstop facility’ from the Reserve Bank of Australia to enable them to honour the government’s commitment without having to sell-off assets:

The Reserve Bank has been quietly working out ways it could establish a government-backed facility to help superannuation funds pay redemptions allowed under new rules to deal with the coronavirus crisis, even though the idea has so far been rejected by the treasurer, Josh Frydenberg…

The government predicts up to $27bn will be withdrawn, but some super funds say redemptions could be as much as $60bn…

Some funds, led by the union-and-employer-controlled industry sector, want the government to underwrite a “liquidity backstop facility” that would provide immediate cash to pay withdrawals. For-profit funds oppose the idea.

There is no suggestion any super fund is at risk of collapse. Rather, industry sources fear that the forced sale of assets would crush their value, crimping returns for people who remain in the fund.

Assistant Superannuation Minister, Jane Hume, has acknowledged industry superannuation funds’ “structural weakness… that has been hiding in plain sight”, whereas Coalition MP, Andrew Bragg, accused industry superannuation funds of “bad management” for being overly exposed to illiquid unlisted assets:

Superannuation funds which may have overextended into illiquid assets, such as infrastructure and property and who did not retain adequate cash and other liquid holdings, did so knowing the risks they were adopting…

The strong investment returns on illiquid assets is, in fact, referred to as the ‘illiquidity premium’, a reward for the risk funds are willing to adopt when they buy these lumpy assets that are hard to sell.

To tout strong investment returns off the back of illiquid assets in the good years, only to come to the government cap in hand when markets inevitably turn, is simply a sign of bad management and poor investment governance…

If prevailing market conditions require superannuation funds to sell assets at depressed prices, and therefore exacerbate poor investment performance, members should be asking hard questions of their fund’s management team and trustee board.

However, University of Melbourne finance professor, Kevin Davis, backed the provision of liquidity support from the RBA, arguing that its is far superior than making industry superannuation funds sell distressed assets at fire sale prices:

…surely, one of the benefits of the super system is that it creates long‐term savings, capable of funding long term illiquid investment in infrastructure which Australia needs. That seems like a natural and good fit (as long as the super funds have the expertise to pick good long term projects).

In this regard they are filling a gap left by our banks which, paradoxically, rely heavily on very short term finance to make longer term housing mortgage assets. That exposes them to liquidity risk, and in circumstances such as this, ability to access liquidity from the Reserve Bank is available by use of repurchase agreements.

Why doesn’t Senator Bragg want similar facilities available to the super funds in the current situation? He appears to think that this would be like a “bail‐out” where taxpayers bear the losses of a private financial institution if it fails due to excessive risk taking, but where the owners of such an institution reap the rewards if successful. But that confuses insolvency and illiquidity.

… a sensible approach, would be to allow super funds to borrow from the Reserve Bank in this way in this crisis period – where extra cash wanted by members is needed because of the change in government policy.

Now, we have a Super offering. So we are not an unbiased observer.

With that disclaimer though, next-generation super funds like ours hold each client’s assets in separately managed accounts. So, you don’t get the problem where the actions of one investor impact other investors who are doing nothing.

Most of the problem, which these funds are admitting by inference, is that the value they are telling everyone the unlisted assets are worth is not the true value. As noted last week by our Head of Investments, Damien Klassen:

A few industry funds have written down assets. For example, AustralianSuper has revalued its unlisted infrastructure and property holdings downwards by 7.5%.

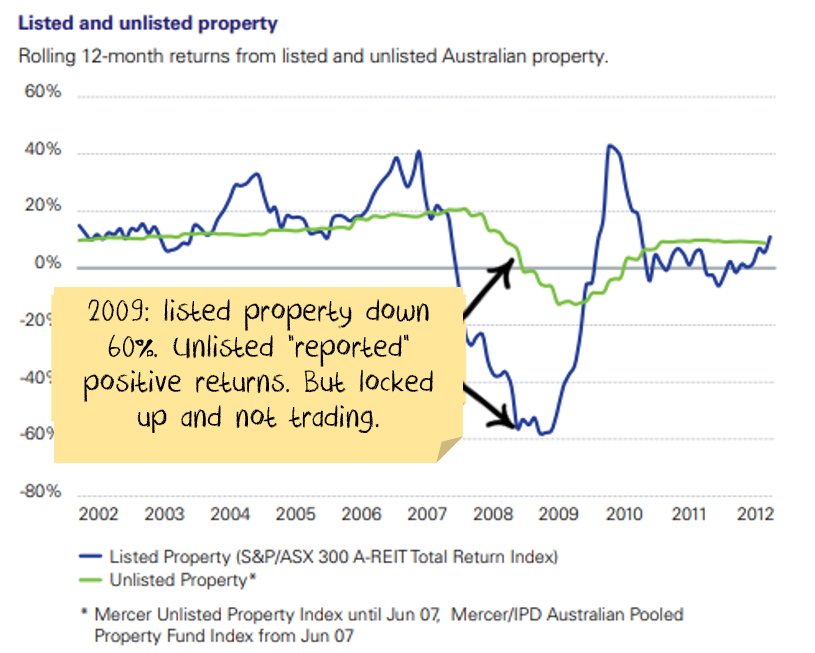

But look at the rest of the market. The listed property sector is off more than 40%. Airports? Down 30%+. Private Equity? Ha! You are telling me that illiquid shares are worth a few per cent less while listed shares are down 25%+ and illiquid bonds aren’t even trading?

The writedowns help, but are nowhere near the level the assets would sell for today…

This, according to Klassen, can lead to perverse incentives and a ‘prisoner’s dilemma’, whereby those that withdraw funds early before assets have been written down will receive an over-sized redemption, whereas those that remain in the fund will have their investment value diluted.

So, maybe the first step should be to actually write down the assets to an accurate value so that people who are leaving don’t shift the cost onto those who are staying?

I’ll leave it to you to decide whether industry superannuation funds’ heavy exposure to illiquid assets is a strength or weakness.

Just be aware that if you are a loyal member of one of these funds, the value of your investment will absorb the losses and could get heavily diluted if enough members take up the government’s early redemption offer and leave.