We have long been of the view that the Reserve Bank is misdiagnosing the economic environment and interest rates are not going up any time soon. Over the past few months, interest rate markets have joined our pessimism and bond yields have fallen – netting a tidy profit on longer-dated bond holdings. After today’s RBA meeting the question is whether the fall bond yields is over or whether there is more to come?

The short answer is no, I don’t think we are there yet – the broad sweep of our strategic holdings over the next few years is to continue to expect central banks to struggle to create inflation. Further, most of the weakness has stemmed from global bond yields falling, we believe there is a further leg down as the Australian economy weakens.

Risk and Reward

Having said that, the risk/reward trade-off has obviously changed. The decision to buy 10y government bonds at an almost 3% yield is different from the decision to keep holding at a 1.7% yield.

Looked at over a longer term horizon, it is important to remember that government bonds cashflows are very, very predictable. Even more predictable than cash:

- When you hold $100 in shares, you don’t know how much you will get in ten years time as principal, and you don’t know how much you will get in dividends.

- When you hold $100 in cash, you know what your principal will be in ten years time but over the next ten years the interest rate is uncertain.

- But, when you buy a government bond for $100, you know how exactly how much interest you will get, when you will get it and when your capital will be returned.

Take the April 2029 treasury bond. You could buy it Tuesday for around $115, it will pay you $3.25 per year in interest payments and in April 2029 you will receive $100 back. Which means if you hold this bond to maturity, you know today you will get a 1.7% per annum return.

Which is a bit sad to be frank. The RBA is targetting inflation between 2 and 3% and so the ten-year bond is giving you a chance to lock in a negative real yield.

But you don’t have to hold to maturity. From an asset allocation perspective, a government bond is a kind of option. You have locked in a 1.7% yield as your hold to maturity return and if you want to sell in the interim there are two possibilities:

- if bond yields continue to fall (weak Australian economy, stock market crash, global economic shock) you will make a capital gain. If the Australian 10-year bond fell to 1% (which is where Canada and Norway bonds bottomed in 2016) then there is another 6-8% upside in bonds. At shorter durations (say in 2-year bonds) there is less upside, at longer durations (say 20-year bonds) there is more upside.

- if bond yields rise (strong Australian economy, global economic boom) you can either hold to maturity for your 1.7% return or sell and take a capital loss. If the Australian 10-year bond rose to 3% then there is 10-12% downside in bonds.

Global Outlook

Most of the recent fall in Australian bond yields has been related to global events rather than local events. The US Fed in particular reversing course and stopping its tightening cycle drove most of the recent downside in global yields. We believe the Australian economy is set to weaken further and that Australian specific factors will see Australian bond yields fall even further.

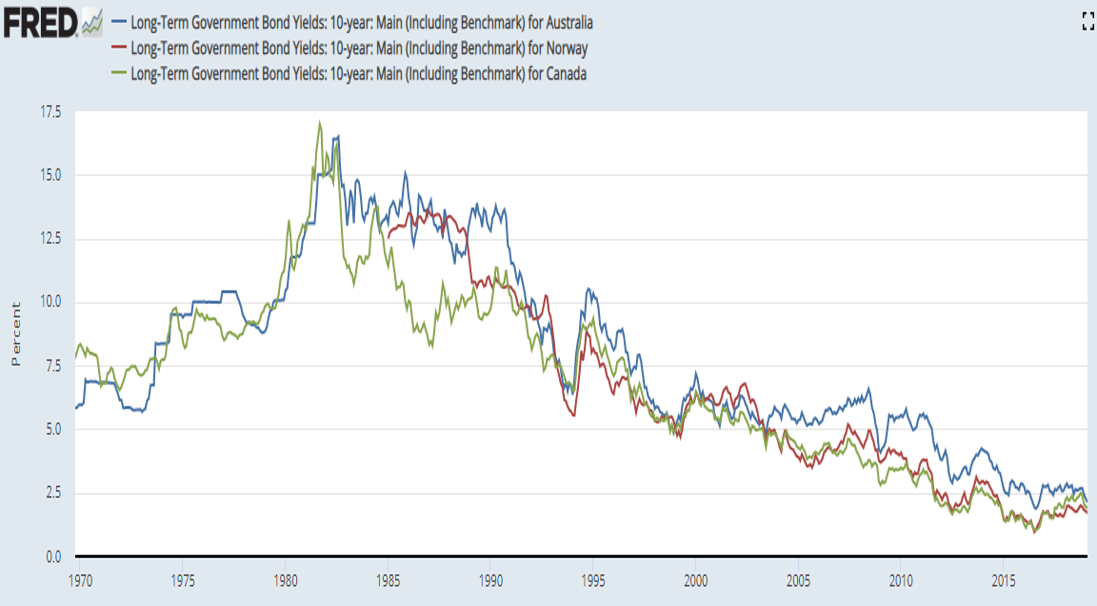

Over the longer term Australian bonds have traded in lockstep with bonds from similar (developed market) commodity exporters like Canada or Norway:

Over the last 5-10 years Australian bonds have has been trading on a premium to international bonds, in our view mainly due to elevated iron ore and coal prices juiced by Chinese demand. Going forward we are expecting this to revert.

Globally central banks have struggled to create inflation – we believe that a mix of demographics, inequality and job automation have combined to keep demand and wages growth low. We do not think that Australia is a special case and Australia has merely been a fortunate trade partner for China which has been fighting weak demand by dramatically increasing its debt burden.

It is important to note also that there are a number of countries with zero per cent ten-year bond yields – Japan and Germany the most high profile:

Relative to these countries, Australian bonds look good value. While we are not of the view that Australian ten-year bonds are going to zero percent, it remains to see how aggressive the Reserve Bank will be – to date they have been conventional in response to conditions. Most “conventional” central banks have interest rates close to zero.

To arrest the decline in bond yields something needs to change – Japan has had 20 years and Europe has had 10 years to show that monetary policy can resolve the issues. It is clear to a growing number of economists that continuing the same policies that created the problem won’t work and structural change is needed.

Australian Outlook

The RBA has a wide band compared to most central banks, despite this Australia is now partly through the third straight year where inflation has been below the RBA’s band.

The bond market is telling the RBA what we have been saying for years – given where we are in the longer term cycle, central bank’s only real lever to create inflation is to blow a debt bubble. In Australia, the RBA (aided and abetted by lax lending standards) has already played that card for consumers. The royal commission into banking is now reversing much of the lax lending standards.

The RBA should have learnt some valuable lessons from other countries that have been through the same process of dealing with weak demand, but to date, the RBA has been very conventional.

The question is whether the RBA has scope to blow another debt bubble? Our expectation is that the RBA doesn’t have the scope to do much on housing (consumer debt already extremely high, house prices now falling), it is possible that a government debt bubble could be created but that is not being contemplated at the moment. Corporate debt is already relatively elevated (globally), and there is relatively limited scope to expand it much further.

What to watch for

WIth this in mind there are a number of things that we are looking for as a sign that government bonds are close to their low point. There are a lot of moving parts and it is unlikely to be just one of the following factors, more likely to be a mix with some factors positively affecting some negatively affecting.

RBA tactics: Traditional

- Interest rate cuts: not many cuts left and the banks will keep most of the cuts

- Blowing debt bubbles: already played this card, there is a government debt bubble that could be created

- Loosening credit standards: already played this card

RBA tactics: Future

- Quantitative Easing (assets): buying bonds and high-quality assets. This can prevent disaster but has not been successful at solving underlying problems. A reason to keep holding bonds as bond yields will likely fall under this scenario.

- Currency devaluation: A lower Australian dollar will restore competitive position. The problem is that many other countries are trying to keep their currency down.

- Quantitative Easing (people): getting money out to the people – whether through MMT, universal basic income or other transfers to get money into the hands of those who will spend it

Other things to watch for:

- 2016 commodity country bond yield lows: Canada and Norway both bottomed out at around 1% yields in 2016 which seems to be a reasonable target for a commodity country’s bonds when the country is struggling with weak demand / recession

- Fiscal spending: A significant increase in government spending will be a sign to close out bond positions earlier. The current budgets don’t count as a significant increase.

- Housing crash: Further weakening of the housing market will be a sign to hold on to bond positions

- Australian dollar: The lower it goes the more likely we are to close out bond positions

- Corporate debt defaults: If corporates start defaulting in meaningful amounts it will be a sign to hold on to bond positions

- Modern Monetary Theory (MMT): if MMT goes “mainstream” then exiting bonds quickly will be a priority. This is unlikely in the short term.

Net effect

- the capital upside from buying bonds is more limited than the downside,

- but capital upside is far more likely than capital downside

We are looking to trim some positions but we are keeping an overweight bond exposure.