IMF debunks "China is different" meme

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) put out a white paper Friday titled “Credit Booms—Is China Different?”

The answer? Not in any meaningful way. Here are some selective quotes and charts (the yellow notes are my comments - and apologies on the IMF's behalf for the poor quality of their charts):

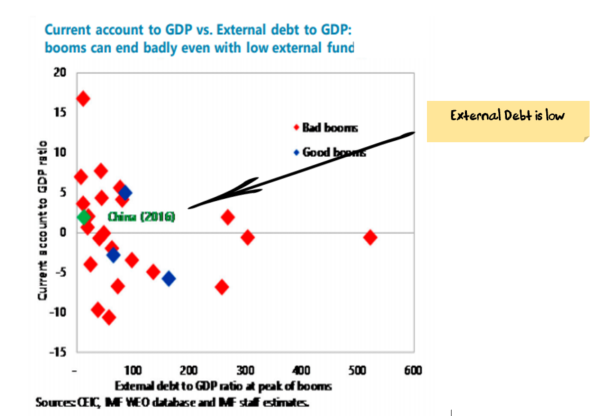

Strong Chinese output growth after the Global Financial Crisis was supported by booming credit. This credit boom carries risks. International experience suggests that China’s credit growth is on a dangerous trajectory, with increasing risks of a disruptive adjustment and/or a marked growth slowdown. Several China-specific factors—high savings, current account surplus, small external debt, and various policy buffers—can help mitigate near-term risks of a disruptive adjustment and buy time to address risks. But, if the risks are left unaddressed, these mitigating factors will likely not eliminate the eventual adjustment, but make the boom larger and last longer. Hence, decisive policy action is needed to deflate the credit boom safely.

Similar to our own view: China does have some specific differences to other economies, but nothing so significant that they can defy gravity forever.

International experience suggests that such rapid credit growth is not sustainable and is typically associated with a financial crisis and/or a sharp growth slowdown.

However, many believe China-specific factors set China apart from historical precedents. These factors include a lack of reliance on foreign financing, low government debt, and state control. Our analysis in this paper suggests that China’s buffers are helpful in mitigating near-term risks. But, if the risks are left unaddressed, these mitigating factors will likely not eliminate the eventual adjustment, but make the boom larger and last longer....

The aftermath of such sharp credit accumulation – credit

busts – tends to be associated with depressed economic growth, sometimes for a prolonged period.

Indeed, the accumulation of debt and subsequent retrenchment have played a role in lowering demand in the U.S., Europe, and elsewhere...

...

During this period, the efficiency of credit expansion has increasingly deteriorated, pointing to growing

resource misallocation....

Source: IMF

When the IMF broke down lending, loose monetary policy and forced lending to infrastructure and mining sectors whose growth did not justify high levels of debt were apparent:

Source: IMF

Empirical results confirm that loose monetary policy is a key driver of rapid credit growth in recent years.

...

Empirical results confirm that industrial structure matters for excessive credit growth. When ... standard determinants of credit are controlled, we find that more credit has flown to those provinces relying more on FAI investment, especially infrastructure investment.

Credit booms of the size of China's tend to end up in banking crises:

...all credit booms that began when the ratios were above 100 percent—as in China’s case—ended badly.

...

The rapid increase and growing complexity in Chinese banks’ balance sheets are another vulnerability. Chinese banks’ balance sheets have expanded by more than 50 percentage points of GDP over the last three years. At 310 percent of GDP, which is above the advanced economy average and nearly three times the emerging market average, China now has one of the largest banking sectors in the world.

...

One particular risk is the sizable maturity mismatch between asset and liabilities. Most banks remain net borrowers in the interbank market, with maturities still hovering near the short end. The maturities of their assets tend to be much longer, by comparison.

There are a number of areas that China is strong (relatively, compared to other credit booms):

Strong asset side of balance sheets. Corporate balance sheets have benefitted from rising asset values, which have increased more than liabilities. As a result, leverage as measured by the debt-to-asset ratio, has been falling. However, asset valuations are highly procyclical could fall sharply were the boom to end (Adrian and Shin, 2012). There is also a mismatch in the structure of liabilities and assets. Corporates’ liabilities are mostly financial liabilities, while a significant portion of assets are nonfinancial fixed assets (e.g. land), which may not be easily liquidated and are subject to sharp valuation changes. In addition, more vulnerable firms—for example, those with lower debt servicing capacity— tend to hold fewer liquid assets, suggesting such firms have lower buffers during times of stress.

...

Ample fiscal space in a state-controlled economy. With official general government debt of less than 40 percent of GDP as of 2016, the government would seem to have fiscal space to backstop the banking system and the broader economy in the event of a credit contraction.

So, can China's strengths overcome the issues of a massive credit boom that is generating lower and lower returns (emphasis mine):

There are several China-specific factors that could mitigate risks in the near term. A current account surplus and small external debt reduce the possibility for a typical external funding crisis as in many other emerging economies. A low bank loan-to-deposit ratio could help prevent a domestic funding crisis as well. Despite the rapid increase in gross debt, corporate balance sheets have also benefitted from asset values that have increased more than liabilities. Policy buffers can also mitigate the impact of potential shocks: the government can use its fiscal resources to backstop the system, the PBC can provide liquidity, and capital controls can contain capital flight. In this section, we analyze each factor to better understand whether they can prevent a credit bust. We find that while these China-specific factors can help delay and mitigate the risk of a disruptive adjustment, they do not eliminate the need for eventual change. Indeed, these factors could just make the boom larger and longer, with higher probability of a more disruptive adjustment.

Key conclusions:

China’s credit boom is one of the largest and longest in history.

Decisive policy action is needed to arrest the negative feedback loop between slowing growth, excessive credit provision, and worsening debt service capacity.

Our view continues to be that China will use the stronger US and European conditions to slow the debt-driven growth and rebalance China's economy away from capex (see our primer for more detail).

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at Nucleus Wealth.

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen is an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management, a Corporate Authorised Representative of Integrity Private Wealth Pty Ltd, AFSL 436298.