Stock markets continued their on/off mode in December. This time it was off. Australian stocks fell 3.2%, international stocks fell a similar amount, but the higher Australian dollar meant they fell 5.4% in Australian dollar terms. Bond yields spiked higher mid-month following changes by the Bank of Japan, but most of that has already reversed.

Energy prices tumbled, largely on the back of an incredibly warm European winter and a bumpy reopening in China limiting oil demand.

The Bank of Japan moved some of its ranges on 10-year bonds, expressing the sentiment that it was merely technical to help market functioning. There are two interpretations:

- The chairperson is retiring in a few months, and the minor changes were better implemented by the existing chair, who has credibility, rather than the incoming rookie.

- This is the first step to the eventual capitulation by the Bank of Japan and rapidly rising interest rates.

The stockmarket and bond market clearly chose the second as the interpretation in the immediate aftermath. We believe the first is more likely. In the last week, the bond market has reversed almost all of the yield increase.

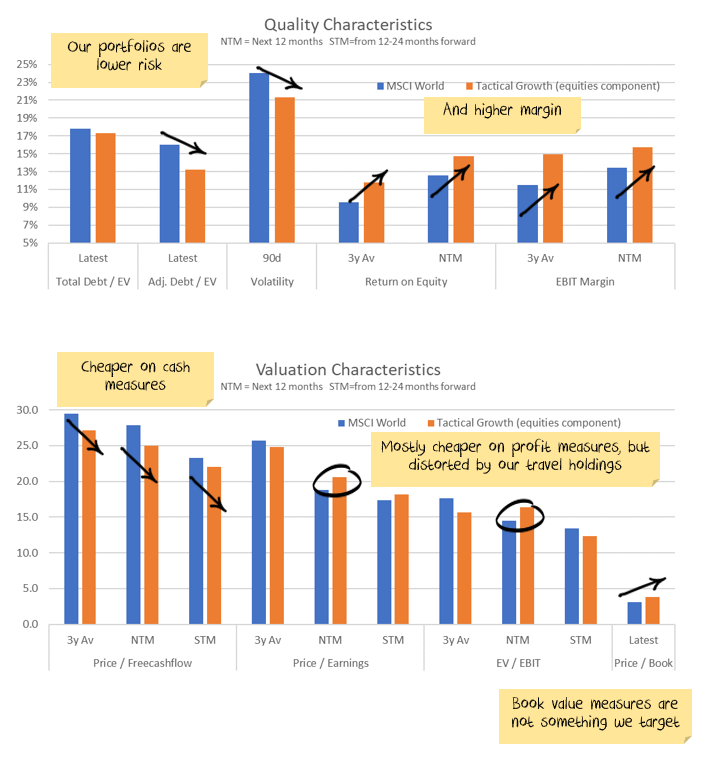

We expect weak stock markets as the central banks raise rates to slow demand, shrinking company profits. With that in mind, the key factor to watch in the coming months to tell if we are wrong or right is the change in corporate profitability. The reporting season in the US showed some signs of weakening earnings, but not enough to confirm our thesis yet.

What is in store for 2023

2022 was all about central banks raising rates in response to higher interest rates and the fallout for markets. Having said that, there were few effects on the real economy from higher interest rates in 2022. 2023 will be about the effects of those higher interest rates on the real economy.

There are four major factors that we believe will shape 2023. A myriad of other factors will make a difference at the margin, but these are the four that will drive investment markets:

1. Corporate Profitability

Typically, in a recession earnings will fall around 20%. Currently analysts still have +3% growth pencilled in for 2023. This is down from a forecast of +10% a few months ago, but it is still considerably higher than the earnings that you would expect in a recession.

With stock markets trading at slightly above ordinary valuations, we would expect that a significant fall in earnings will translate relatively directly into a significant fall in share prices.

So, the number one question for stock markets is whether earnings fall 5% or 25%. Currently we are expecting earnings to fall at least 10%, with risks to the downside if central banks hold on to higher rates for too long.

2. Inflation

Inflation is clearly weakening. We are seeing deflation in transport, deflation in goods. But services inflation is still running hot, particularly in the US.

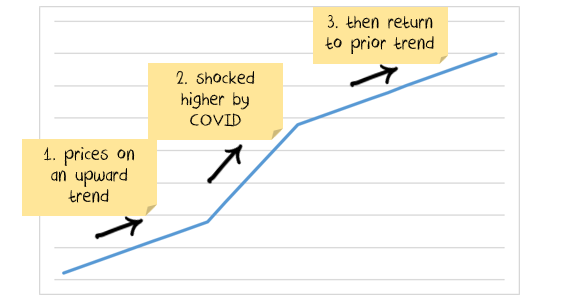

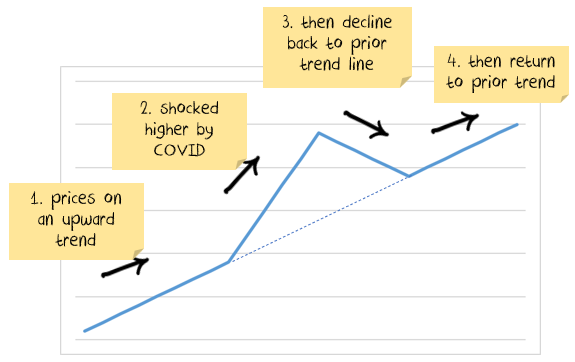

There are two ways to consider reversion:

1. While central banks will force inflation back to 2%, prices will remain structurally higher.

2. Prices have been temporarily shocked, but will return to the prior trend

Goods are probably more likely to be in the second category, services more likely to be in the first.

The shape of future inflation or deflation depends on how many things you think will fit into each profile.

We continue to expect central banks to want ensure that inflation is completely snuffed out before switching. Central bankers do not want to be remembered as Arthur Burns, the Fed chair who was getting on top of inflation in the 1970s before reversing too early. They want to be remembered like Paul Volker, who slayed inflation. The double dip recession that Paul caused to do so is treated as a minor footnote.

3. Chinese re-opening

China has had four attempts in the past dozen years to wean itself off its property construction addiction. They lost their nerve on three prior occasions. It looks like they have done so again, after removing the reference to “houses are for living, not for speculation” from their communications.

As we discussed in prior months, exiting COVID is going to be bumpy in China. Economic indicators are going to be misleading, affected by short term issues. There will be stops and starts:

- It is likely, in the first instance, that the private sector will lock down anyway as the virus tears through.

- There are questions about how long China will take before emerging. We don’t expect an economic emergence to take long, but I’m not sure.

- There will likely be a re-opening boom. How long it lasts has many questions. Because China already had a re-opening boom after the original lockdowns, will this one be smaller?

- China did not transfer as much to ordinary citizens as many other countries – there will be pent up demand but it may be less than elsewhere.

- But, we also need to recognise that the announced property measures so far are not enough to re-ignite the property boom. There will need to be more announcements.

- And if more property announcements do not come, investors will need to be ready to pivot. In that scenario there is considerable downside for the Australian dollar and commodities.

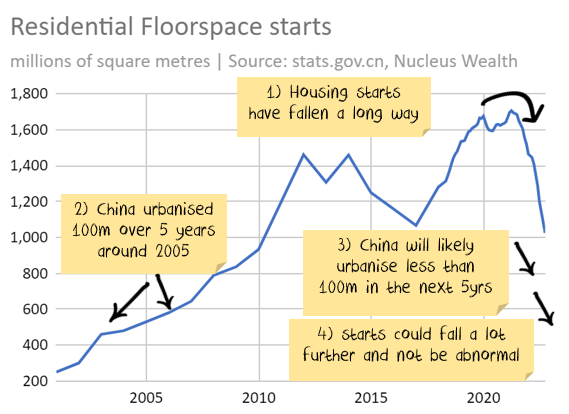

As we discussed last month, for the Australian economy, it mostly hinges on property.

The question now is what is the right level for housing starts to return to:

- If you benchmark to the last 5 years, housing starts could grow 60%.

- If you measure it by other countries (including China itself), housing starts could fall another 40% to reach the level of similar countries.

So, if the building boom is genuinely back, it will take time to see the effects.

Three areas to watch:

1. Credit locking up in the property development sector.

Not happening any more. What was a risk two months ago has now become a footnote.

Government support has led to considerably higher debt availability.

There is a question of whether property developers want more debt after a near-death experience. But we aren’t going to know that for months given the re-opening issues. Many commodity prices are already pricing a boom, which is why we closed out our underweights to resources last month. There is risk to the downside if the property boom does not re-ignite – but it is too early to trade that. We will wait for more evidence.

2. Property buyer confidence

China has some of the most expensive housing in the world relative to income. Should buyers lose faith in the value of properties, then a house price crash could result. This could occur even if the first issue is solved. Which would leave developers in a much worse position.

There are signs that Chinese property buyers are spooked. There is not a lot in the measures to solve this problem. Watch this space.

3. House price wealth effects

This is the problem facing almost every country. High property prices increase inequality, reduce economic growth and damage productivity. But all of those are longer-term problems.

The short-term effect of rising prices is to increase spending and consumer confidence. And politicians love short-term gains at the expense of long-term losses. Falling home prices offer the opposite.

The problem is worse for China than elsewhere. Both homeownership and investment in real estate are much higher in China than in most other countries.

4. The effect of last year’s interest rate increases on the Australian economy

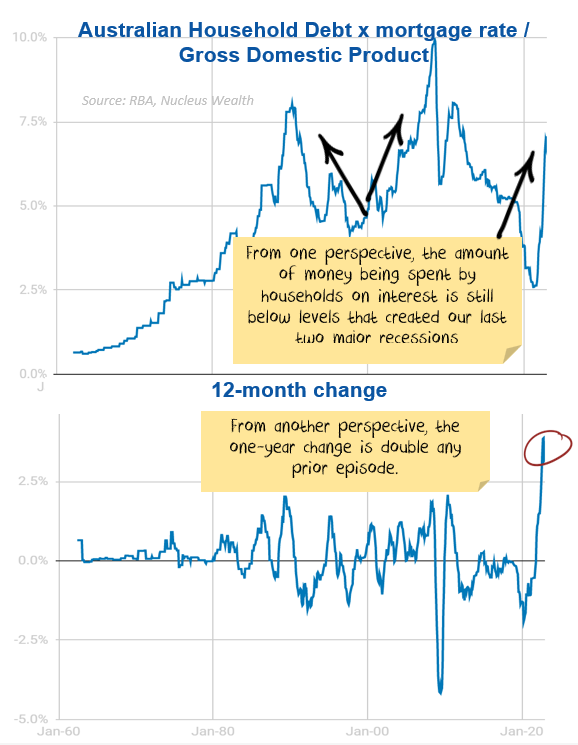

The Australian consumer is in the process of going through the largest increase in interest rates ever. As a proportion of GDP, the increase in interest costs is looking to be about double prior episodes:

However, these changes do not happen immediately:

-

- Delayed direct impact of rate rises. Typically rate rises take 2-3 months before affecting cash flow for a borrower.

- Delayed effect due to greater than usual concentration of fixed-rate mortgages. In March 2020, the Reserve Bank introduced a facility where they lent directly to the banks at 0.1% for three years. This facility (and other market interventions) allowed banks to drop three-year fixed mortgages to around 2%. In response, fixed mortgages went from 10-15% of refinancing to over 40%. These will roll off, but in the interim, there are far more people who will be unaffected by the rate rises until they refinance.

- Delayed indirect impact of rate rises. Even after the cash flows of borrowers have decreased from the rate rise, it still takes time for them to actually notice and change their spending patterns. So, for businesses that rely on consumer demand, it can take another few months before the effect flows through.

- Delayed 2nd order and above effect. The economic multiplier compounds the effect for months going forward. i.e. consumers spend less (say) on eating out which means that restauranteurs have less money to spend and then may lay off staff who also reduce spending. The effect of this echoes multiple times through the economy. Typical estimates suggest 1-2 years for changes in monetary policy to have the full effect.

The net impact is that the economic impacts, and the impact on house prices, have yet to take full effect. Even the first rate rise in May 2022 hasn’t seen the full impact on the economy.

The interest rate rises will hit the Australian economy in 2023. The extent of the damage to consumption will determine the investment outcome for many Australian stocks. We believe that a change in interest rates equating to around 4% of GDP is too large for the Australian economy to handle without slipping into a recession.

Net Effect

Investing is always a trade-off between economic outlook and price. Prices look expensive, the economic outlook is troubled.

Have we seen this all before?

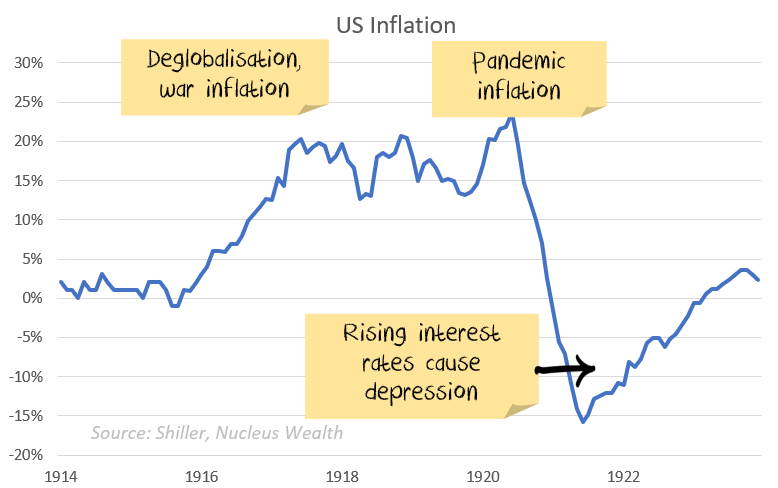

- Globalised supply chains reversing into more local production due to geopolitical tensions

- A pandemic disrupting supply chains

- A surge in inflation due to supply issues

- Central banks hiking rates into a supply-side shock

Yes, we have. Following World War I, all of the above factors were in place.

By 1920, inflation in the US was running at 15%. The US central bank hiked rates from 3.5% to 5.6% to curb demand. By 1921 the US was in a depression, with inflation of -10%.

The analogy is not exactly the same. But, trying to use interest rates to solve supply chain problems is at the core. There are more similarities than there are differences.

Investment Outlook

I have some pretty clear ideas about which trends are sustainable and which ones aren’t in the long term. However, the short-term is far less clear:

- The sanctions on Russia are unlikely to be lifted anytime soon. The short-term effect was commodity shortages. In the longer term, it seems likely that we will see a re-orientation, Russia will supply more to countries like China and India, less to Europe. For some commodities (oil, wheat) this will be easier. For others (gas) it will be extremely difficult.

- The Omicron variant looks to be resolving in the direction we expected, ripping through economies without too much harm and leaving behind an acceptance that COVID is endemic. In China, rolling lockdowns have finally finished.

- The geopolitical energy crisis in Europe has eased on the back of much warmer weather. Australian energy price caps have pushed down energy prices. There will be a rush to alternative energy sources in the long term.

- Supply chains continue to improve.

- Governments continue to withdraw (or not replace) stimulus. There will be a fiscal shock into 2023. The question is whether the private economy will be strong enough to withstand it. Leading indicators suggest profits will be lower.

- Central banks have made it clear that they will try to solve the Russian-induced energy issues and supply chain-induced inflation by raising interest rates. The odds of a policy error have increased significantly.

- China still has not bailed out the property sector. The latest changes are not a bailout… but they may morph into one. China is trying to ensure that houses under construction get built, small businesses have access to credit, infrastructure building continues, and failing developers do not crash the economy. China is yet to show any signs of turning back to the old days of debt-driven property developer excesses. In the short term, commodities have been booming. If China doesn’t continue to roll out new measures, the commodity market will deflate again.

It is still not the time for intransigence. Events are still moving quickly. But we have positioned the portfolio towards the most likely outcome and are gradually increasing the weights as more data arrives.

Bond yields have risen significantly. If the world heads for recession this is a buying opportunity. In the short term is that the narrative “high inflation, central banks raising rates = sell bonds” seems to be coming to an end. Although there may be another last hurrah as the US central bank looks to rein in the stock market optimism.

And the mix of higher volatility, leading to deleveraging of risk parity trades and momentum means yields could yet go higher. We are invested for bond yields to reverse.

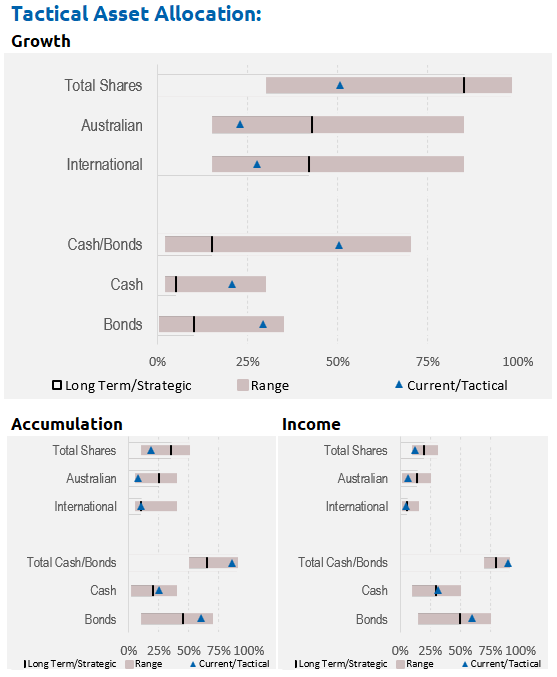

Asset allocation

After being very expensive for a number of years, stock markets are now flirting with fair value. Debt levels are extremely high. Earnings growth had been really strong but has come to a halt. There are signs it is starting to reverse.

Markets are supported to a great degree by central banks and governments. Policy error is every investor’s number one risk.

But, any number of other factors could force this off course and see unexpected inflation. COVID mutations could disrupt supply chains again. Chinese/developed world tensions might rise further, leading to more tariffs. Or, China might reverse its tightening on property sectors.

We are significantly underweight Australian shares, and as noted above, overweight bonds, with the view that the Australian market is more quickly affected by rising interest rates and more affected by a global recession:

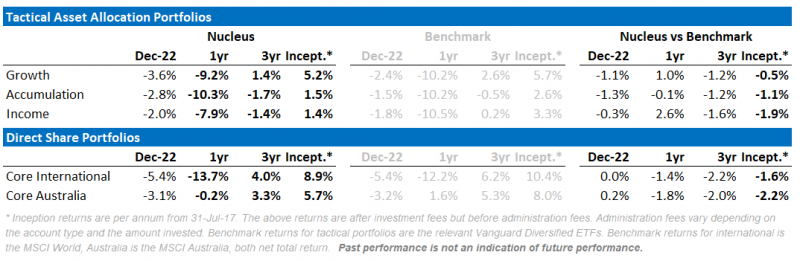

Performance Detail

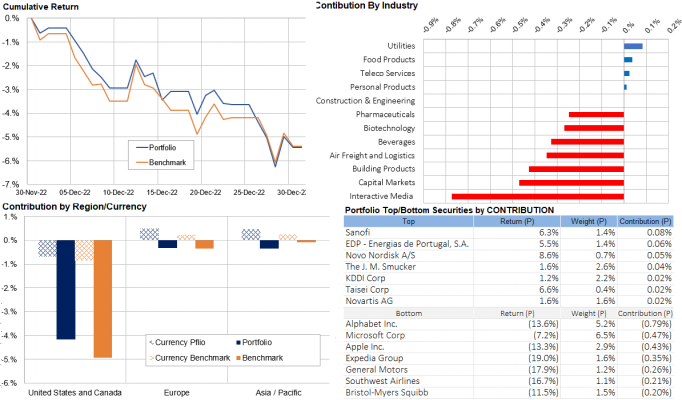

Core International Performance

The Santa Rally ended abruptly and went into sharp reverse over December as the Fed hosed down any expectations of pauses in interest rate hikes. The downward grind was almost universal with the recovering Tech stocks sold off the most. The US fared the worst as European and Asian stocks booked only minor declines. Despite the December declines, the final 2022 quarter eked out a 4% gain from international stocks. While we reduced our equity weighting in the Tactical portfolios, we maintained their current composition.

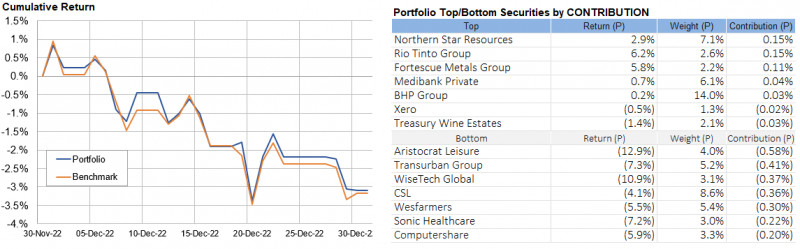

Core Australia Performance

Australian indices followed the global downward trend. But, the about-face in China on COVID-19 policy meant the prospects for resource stocks improved and thus they continued to rally into December. Our move back into resources meant we matched the index. We made no other changes this month.